Greetings Austenites—

I’m back with the fourth installment of Austen Math, in which I quantitatively evaluate Jane Austen’s single men and her heroines’ judgment of them.

Today we will explore the lush grounds of Mansfield Park. If you’re new to the party: welcome. Feel free to join us in the tangled wood posthaste, or if you prefer the linear path, start here:

I also spoke to

of The Common Reader recently, and our conversation serves as a nice summary of the first three installments.A few other transitional notes on the third:

I can’t help but feel the wisdom of my father’s reading order—that is, Emma before Mansfield Park, though the former was written and published later—all the more strongly after finishing both books. Emma is the better novel, but Mansfield Park is the more complex. It is in Mansfield that Austen transparently works out the most sophisticated mechanics of desire; in Emma, she unites them in full maturity to the sparkling wit of Pride and Prejudice, deploying both together to their subtler yet greatest effects. If Emma is the ultimate magic trick, Mansfield Park quite literally lets us peer backstage. There is no question which view most of us are better equipped to process.

I’m not going to dive whole hog into a Girardian analysis of Mansfield Park—for that, I will direct you to this excellent article (via Henry) examining its mimetic rivalries in the relevant context of another of the novel’s obsessions: landscaping. There are, however, two points I want to emphasize of particular relevance to Austen Math:

The love triangle between Henry Crawford and Maria and Julia Bertram is a textbook exploration of Girardian internal mediation spiraling into double mediation, from the similarities of the sisters to the gentleman’s outsized appeal to the nature of his choice between them. Henry Crawford is truly the Pete Davidson of Jane Austen—and, for all of Rushworth’s protestations, his scores must reflect it.

Fanny transforms from the novel’s scapegoat into its heroine precisely via anti-mimesis—in resisting the very man over whom her cousins lose their minds, she both catalyzes and resolves the novel’s mimetic crisis. This dynamic sharply informs today’s heroine model—which for the first time must be considered an antiheroine model as well.

Is the Mansfield line between hero and antihero similarly murky? Anticipatory comments suggest so.

writes: “Regardless of what score you give Edmund in Mansfield Park, I will always consider him to be the absolute worst excuse for an Austen hero. Ugh!”Similarly and conversely at once, Anne (very charmingly) admits:

Excited for the evaluation of Henry Crawford! I have always had a decided partiality for him; for my money, there is nothing like a short charismatic man troubled by his conscience. I fear what that says about my Austenian judgement score.

One last thought before letting them all duke it out, admittedly a self-indulgent one: I could not be more delighted to see Austen Math sparking interest in The Portrait of a Mirror. Thanks to those who’ve picked it up!

’s judicious review in particular has me thinking of it alongside Mansfield Park. Any comp to the GOAT is hubris, of course, even one of imperfections; still, I cannot help but see the novels sharing a similar flaw. They expose mimetic desire too transparently—for many, disagreeably so. I can only hope (as I did consciously intend!) that my new novel on submission corrects for some of this in its Girardian maturity, even if it is still a tragicomedy. Perhaps I’ll aim to scale Emma’s pure comedic heights in the next one.Austen Math 101

Jane Austen, arguably the greatest novelist of all time, was the author of six marriage-plot comedies of manners published between 1811 and 1817: Sense and Sensibility, Pride and Prejudice, Emma, Mansfield Park, Northanger Abbey, and Persuasion. There is rampant dispute as to how to read them. “The people who read Austen for the romance and the people who read Austen for the sociology are both reading her correctly,” Louis Menand argues, “because Austen understands courtship as an attempt to achieve the maximum point of intersection between love and money.”

Menand’s vaguely mathematical binary is directionally accurate but insufficiently sophisticated. Austen is absolutely a marital maximizationist, but her calculations have far greater dimensional depth. As such, neither the die-hard romantics nor sociologists are reading her correctly; they are equally mistaken. Over- or under-weighting any single dimension of Austenian courtship maximization amounts to a fundamental misunderstanding of what she most cunningly gets:

Austen understood status—ahem, station; that its shoring up is hardly superficial. The intrigue of the marriage plot springs not just from uncertain affection—“will they fuck”—but the balance of such possibilities with a complex and often competing set of considerations. Status questions, basically, though to the standard socioeconomic strains I would add, particularly in Austen’s case, that of moral status. Alas, fuckability is a kind of status, too.

The Austen Math model more or less directly follows my original offhand vision, ranking all of Austen’s single men across four weighted dimensions—fortune, morals, manners, and fuckability—to develop secondary insights, calculate their individual total status, and analyze their relative marital desirability. The heroines, in turn, are judged by their dimensional weighting (and to what extent it shifts over time) versus the Austenian baseline. In other words: they are judged on the soundness of their judgment. The better a heroine is at Austen Math herself, the more virtuous she is deemed.

And what of love per se? Even the most sophisticated mathematical models are simplified phenomenological representations. Indeed, this is the purpose of models. I’d argue love is largely represented indirectly by a proprietary mix of the various dimensions—but I do not claim to capture all of Austen’s complexity, let alone any universal truths.

Methodology*

I. Dimensional raw scoring of single men

Each single man is evaluated on each of the four primary status dimensions of FORTUNE, MORALS, MANNERS, and FUCKABILITY using a whole-number score of 1 to 6, one being low and six high, based on textual analysis by yours truly.

My definitions are as follows, with help from Merriam-Webster (MW):

By FORTUNE (n), I mean “riches; wealth,” in line with MW 1.2, “a man of fortune.”

By MORALS (n), I mean both “ethics” and “modes of conduct,” per MW 2.2a-b, in the context of Christian Regency norms without blind deference to them.

By MANNERS (n), I mean personal bearing, air, deportment, style, etc., running the gamut of MW 1a-e, again filtered through a critical Regency lens.

By FUCKABILITY (n), admittedly not in MW, I mean sexual desirability, predominantly but not exclusively based on physical attractiveness, also including demonstrable charm, wit, and je ne sais quoi.

The six-point scale both allows for sufficient differentiation across Austen’s six novels and forces non-neutrality.

II. Austenian primary status weighting (baseline)

The four primary dimensions predict total status via uneven weight distribution, in alignment with the hierarchy of Austen’s values as I have long understood them:

MORALS - 40%

FORTUNE - 30%

MANNERS - 20%

FUCKABILITY - 10%

for a total of 100%.

The formula to calculate total estimated Austenian status is a basic SUMPRODUCT: D1*W1 + D2*W2 + D3*W3 + D4*W4, where D=dimensional raw score and W=Austenian weight.

III. Secondary dimension calculations

Each pair of congruous primary dimensions yields insights into a secondary dimension. At the intersection

of FORTUNE and MORALS is WORTH,

of MORALS and MANNERS is CHARACTER,

of MANNERS and FUCKABILITY is AFFECT,

and of FUCKABILITY and FORTUNE is ELIGIBILITY.

Secondary dimension calculations may be performed either via weighted or unweighted averages of their raw inputs to harness insights inclusive or exclusive of Austenian status bias, respectively.

Note the secondary dimensions get closer to viscerally lovable personal attributes—character, affect—but would be harder to directly quantify themselves (e.g.: worth is more subjective than fortune).

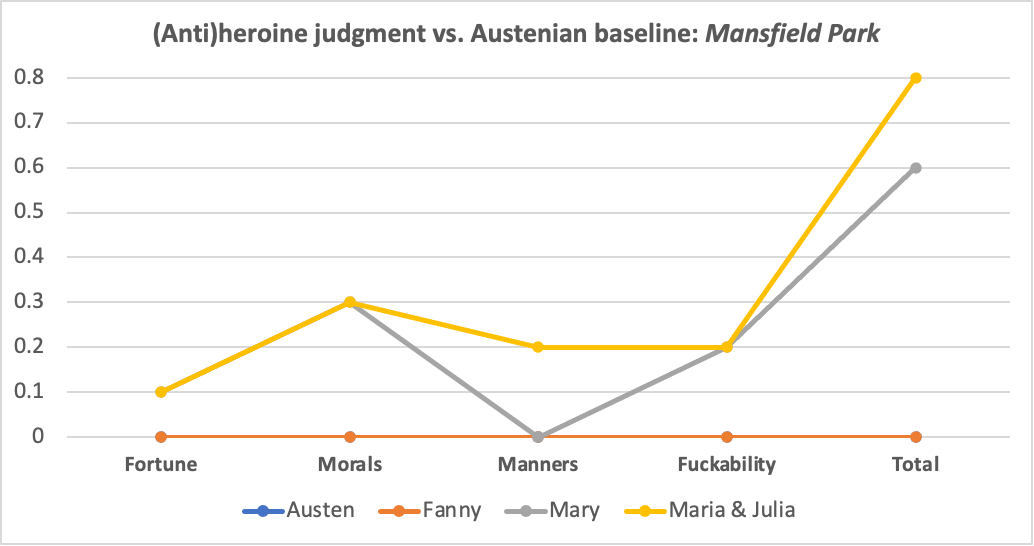

IV. Heroine dimensional weight variance

Each heroine is evaluated on the difference between her hierarchy of the four primary status dimensions (again per my textual analysis) and Austen’s. Like in the Austenian baseline, the heroine’s top-priority dimension is weighted 0.4, with -0.1 for each subsequent priority.

The formula for dimensional weight variance is: |W1-H1|+|W2-H2|+|W3-H3|+|W4-H4|, where W=Austenian baseline weight and H=heroine weight. I use this absolute-value “spread” calc over true squared variance for its simplicity, clarity, and sufficiency given the small size of the data set. The score will fall between 0 and 0.8 in increments of 0.2, and can be roughly interpreted as follows with regards to the heroine’s judgment:

0 - Unimpeachable

0.2 - Sound

0.4 - So-so

0.6 - Precarious

0.8 - Misguided

I.e., the lower the score, the better her judgment. In some cases, heroines’ dimensional values change over the course of the novel, in which cases I calculate both starting and ending hierarchy for comparison to estimate their development.

*Feel free—nay, encouraged—to quibble with any of this. We are here first and foremost to have fun, and banter is damn close to my definition of it.

Credentials

While admittedly an amateur Austen scholar, I am the daughter of a doting professional one—and a professional novelist and management consultant myself (see: Portrait, patents). My undergraduate degree is in English and my graduate an MBA: a thoroughly Austenian compromise. Her voice has been inseparable from that of my own conscience since I was ten years old.

Part 4: Mansfield Park

Few social taxonomies convey information more densely than relation to a grand estate. In the case of Mansfield Park: Sir Thomas Bertam is master; Lady Bertram his consort. Their four attractive children—Tom, Edmund, Maria, and Julia—comprise the rising generation. Lady Bertram’s sister, Mrs. Norris, and her husband live less grandly but still comfortably nearby at the Mansfield vicarage, thanks to Sir Thomas’s beneficence. To Lady Bertram’s other sister, Mrs. Price, and her nine (9!) children, poorer still, a sense grows that something more is due. And so ten-year-old Fanny Price comes to Mansfield Park—far more to her mother’s relief than her own presumed benefit from the society of her elder cousins, perhaps with the exception of Edmund.

Years pass. The Rev. Mr. Norris dies, and the vicarage passes to Dr. Grant; Sir Thomas is obliged to leave Mansfield for business in Antigua; Maria and Julia become the belles of society, the former securing an engagement to obscenely rich Mr. James Rushworth. Fanny’s concerns are, as ever, decidedly secondary—especially after Mrs. Grant’s ubër-charming siblings, Henry and Mary Crawford, arrive for a visit. Mansfield Park is now full of under-supervised young people, coming together in gardens and woods, parlors and a play, brimming with desire and temptation. What could go wrong?

The single men

Mr. Tom Bertram; Mr. Edmund Bertram; Mr. James Rushworth; Mr. Henry Crawford

Fortune

As the eldest son of Sir Thomas, Tom Bertram is heir to Mansfield Park and his father’s title, as well as the property in Antigua. Much as he might play at master of the house in his father’s absence, none of this is yet his—and for the majority of the novel, he shows a profligate streak. 4/6.

To Mary Crawford’s dismay, Edmund has firm plans to brave second-son syndrome by taking orders. He can expect a nice living of 700£ a year at Thornton Lacey, but in the tradition of past clergymen maxes out at 3/6.

Rushworth’s estate, Sotherton Court, might not have quite the natural charm of Pemberley, but his astronomical income of twelve-thousand pounds per year makes him Austen’s richest man. 6/6.

Henry Crawford earns 4,000£ a year from his estate, Everingham—a more than comfortable seat, fully in his possession. He scores 5/6.

Morals

Both Tom and Rushworth display that sort of half-forgivable default selfishness so common in privileged young men. They are devoid of malice but also any moral interrogation, only too happy to claim every benefit they’ve been socialized to expect. In Tom this manifests more in shirking responsibility for pleasure, in Rushworth, comically outsized self-importance (his “two and forty speeches” in the play!), but the result is the same: 3/6.

To similar carelessness for similar reasons Henry Crawford adds the far greater sin of cruel intent. While Maria Bertram is not exactly some blameless ingenue in their tryst, Henry’s seduction of her involves significant forethought and little compunction. Even the genuine admiration he develops for Fanny traces its source to his own vanity; “my plan is to make Fanny Price in love with me,” he tells Mary. With the utmost compassion for any readers nonetheless seduced by him, he can only get 1/6.

So Edmund is clearly the most moral of the bunch, even if this doesn’t amount to particularly high praise. I’m wary of overrating his kindnesses to Fanny merely on the basis of his comparative decency, but so too am I of modernly underrating his disapproval of the play or unwavering commitment to the Church in spite of Mary’s temptations. His judgement isn’t perfect, but Edmund’s resistance to that which he knows to be wrong must ultimately outweigh his attractions to it. 5/6.

Manners

Both Bertram brothers don excellent manners. Tom “had more liveliness and gallantry than Edmund,” but Edmund catches up here on extended acquaintance, as his greater thoughtfulness rises to the surface. Between Tom’s instrumentalization of Fanny to avoid playing cards at the ball and Edmund’s amnestic moments (recall the horse), neither can be held up as paragons, but both still get 5/6.

Henry Crawford is a paragon on this front, however—a skilled, protean one, pleasantly contorting himself to his intended audience. With the Miss Bertrams, he shows “so much countenance” as to be deemed “the most agreeable young man the sisters had ever known.” It is no coincidence he is the best stage actor! Even Fanny is not insensible to Crawford’s charms, once he centers them on her: “she thought him altogether improved since she had seen him; he was much more gentle, obliging, and attentive to other people’s feelings than he had ever been at Mansfield.” 6/6.

Rushworth has no such dramatic talent. His manners reflect his simple vacuity—empty of offense, but also anything to recommend them. He scores 3/6.

Fuckability

Rushworth’s fuckability follows suit. “He was a heavy young man,” but “there was nothing disagreeable in his figure or address.” 3/6 yet again.

The other three young men all bunch together here, if via different means. The Bertrams are taller and handsomer, but Crawford somehow still equals them—je ne sais quoi. Rushworth can’t understand it—and in his defense, Deceit, Desire, & the Novel is not an easy read—but all things considered, material and metaphysical, I can only give 5/6 to all three.

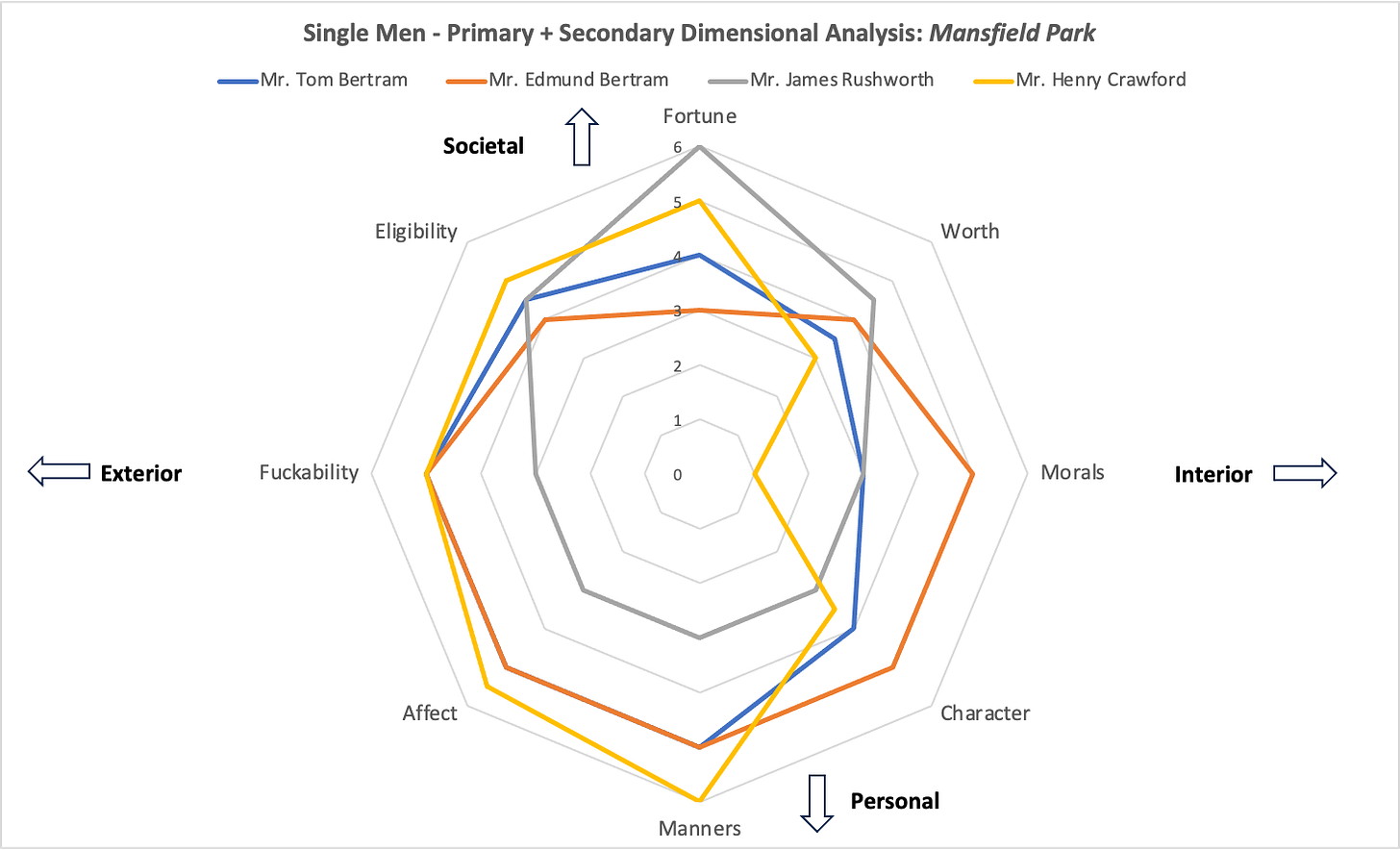

Secondary dimensions & insights

No surprise: the spider chart is a tangled mess!

I say no surprise given how mimetic the novel, which likewise brims with intersections and overlaps. Brothers, rivals. You can graphically see the struggle to differentiate!

And yet, as ever, “nothing highlights difference quite like homogeneity,” and the longer I look at this, the more interesting the shapes that emerge. Rushworth’s ultra-rich teardrop of mediocrity is a new one, as is Crawford’s kidney bean (the sins of Austen’s earlier seducers—Willoughby, Wickham—cannot be so cleanly split from want of money). It’s the most fortunate and eligible cast of young men we’ve encountered overall, and in the tradition of messy rich people narratives, this detracts from the superficial drama while enhancing more sophisticated ones. Is it any wonder Mansfield Park tends to be a favorite more among the professors than the romanticists?

Weighted Austenian Total Status Model

The single mens’ similarities grow only more pronounced when we look at total status:

For the first time, two characters—Tom and Rushworth—receive the exact same score. And Edmund and Henry aren’t far off from them. All four fall within a single point of each other.

The (anti)heroines

Miss Fanny Price; Miss Mary Crawford; Miss Bertram (Maria); Miss Julia (Bertram)

While Fanny eventually becomes Mansfield Park’s one and only heroine, the role is hotly, doubly contested in the novel’s first half. It’s not even clear she’s a candidate early on;—Fanny is a pale shadow of her cousins in wealth and affect, and second to Mary even in Edmund’s heart.

Nowhere is this dynamic clearer than in the play, Lovers’ Vows. Maria and Julia compete viciously to star opposite Henry Crawford, while Mary’s given the other female lead, opposite Edmund against his better judgment. So none of them can be dropped from the heroine model so easily; it is only on Sir Thomas’s (in)opportune arrival that the tables begin to turn. Given Maria and Julia trace their differences almost exclusively to the outcome of their mimetic rivalry, though, I will consider them together:

The Bertram sisters value affect above all. Whether we say manners then fuckability, or fuckability then manners (followed by fortune, then morals), the math is the same: 0.8 - Misguided. Rushworth’s wealth can provide only temporary consolation to Maria for Henry Crawford—and Julia’s rejection is her saving grace. After Maria runs off with Henry, Julia follows suit in eloping with Yates. It’s a lesser crime largely by luck.

Mary likewise undervalues morals, but her more pragmatic priorities do not expose her to quite the same level of disaster. They are:

FORTUNE

FUCKABILITY

MANNERS

MORALS

For an Austenian judgment score of 0.6 - Precarious. She topples decidedly on its bad side, losing Edmund in the process.

As for Fanny: she is unwavering, a “heroine who is right” all the way, with a perfect Austenian score of 0 - Unimpeachable. While her refusal of Henry gives the appearance of coquetry, no such intention undergirds it. The drama of the novel lies not in her moral development, but in her abiding justice’s gradual exposure. Edmund is her reward.

Other misc. notes from this read:

The name “Fanny” is absolutely horrible and I cannot help but wonder if this alone hardens readers against her.

On several occasions Austen slips into the first person! I thought I was hallucinating this for a moment, but no. Just one example:

for although there doubtless are such unconquerable young ladies of eighteen (or one should not read about them) as are never to be persuaded into love against their judgment by all that talent, manner, attention, and flattery can do, I have no inclination to believe Fanny one of them [emphasis mine]

Love Lady Bertram’s pug. Nothing better than a frilly little dog in serious literature.

Another note on Lady Bertram: she is the original “flat character”—Forster’s exemplar in Aspects of the Novel.

“Fanny was her oracle,” Austen says of Susan, prefiguring not only her replacement of Fanny as their aunt’s companion at Mansfield, but the even more pronounced foresight of one Mr. George Knightley.

NEXT UP: Northanger Abbey. I’m going to admit that it left a lighter footprint than the others on my young mind; it’s the only one of Austen’s novels I’ve read just once. But now this makes me all the more eager to dive in—to probe and question my slants and follies—

Until then—

ANJ

You might be hesitant to compare your work to Austen, but it is so apt! It's hard to think of a novel that reminded me as much of Austen than yours without becoming full-blown pastiche. I'm so looking forward to reading your next novel, whenever it makes its way into the world!

I just finished a reread of Mansfield Park last week so this landed in my inbox at the perfect time. I find MP the most baffling of Austen's novels, but I love rereading it because I feel like each time I inch a bit further towards some understanding of it. Your insights about the mimetic nature of the book are illuminating, and I'm looking forward to reading some of what you've linked here. Thanks for another great post! Enjoy your Northanger Abbey reread...it's my least read Austen as well so I might try to pick it up before the next Austen Math installment!

Wonderful as usual. I have only a slight regret : I wish you had also scored the eligibility of the single women on the same four criteria.