All the single men: Emma

in which comparative status reaches new heights of clarity and equivocation

Greetings Austenites—

I return to you with the third installment of Austen Math, where I quantitatively evaluate Jane Austen’s single men and her heroines’ judgment of them.

If you’re new here: welcome. Each installment is intended to be enjoyable on its own, but for the very best experience, start here:

Today we have Great-English-Novel candidate and my own reigning personal favorite, Emma. Why not Mansfield Park, which was written and published first? Because this is the order in which my father first read them to me. When I recently asked him why, he said: “Mansfield Park is Austen’s most complex novel, and you were young.” I must bow to tradition here. Consider it house rules.

Before we dive in, a few notes coming off the second installment:

With great delight, I received an answer to my question on what Austen could have been at naming Jane Bennet Jane.

writes:One of my grad school advisors had a theory that Austen only ever named the overly sweet / near perfect characters Jane as like a joke to her family and friends! (Like Jane Fairfax in Emma!)

I love this theory and hereby endorse it till further evidence suggests otherwise.

There were also comments, as well as a heartier response from

, regarding my analysis of Mr. Collins. [sic, no relation] writes:Against all this we must be reminded that, as Joy Clarkson says, Mr. Collins is living his best life now: https://www.plough.com/en/topics/culture/literature/why-we-should-envy-mr-collins

There is certainly some truth here. Mr. Collins’s thankfulness and specifically contentment in his position are indeed Austenian virtues, emphasized still more forcefully in the novel we will consider today. Miss Bates’s prolix obliged-ness carries all of Mr. Collins’s absurdity with none of his conceit, and Emma is severely chastised in outwardly poking fun at her—even as Austen agrees with the charge. As I put it at eighteen, and can scarcely do better now: “Emma, a wrong heroine, speaks the truth, but a truth that should not have been spoken.”

However—and it is an emphatic however—Mr. Collins’s thankfulness neither precludes nor diminishes his selfishness any more than it does his absurdity. Austen is not insensible to luck, and Mr. Collins hardly her only character blessed with more than he deserves. Willoughby gets Miss Grey’s fifty-thousand pounds (a fortune larger than Emma’s); Wickham is received with Lydia at Longbourn. Frank Churchill wins the heart of a near-perfect Jane! If Austen’s heroines gratifyingly succeed in outsized proportion to reality, so do to her villains prosper in greater alignment with it. This is no small part of Austen’s comedic genius—part of what makes her novels moral without being moralizing. For even as she japes and excoriates her characters, Austen is also unfailingly generous to them.

Now, how generous—and how excoriating—will the Austen Math model be to Messrs. Knightley, Elton, Churchill, and Martin? You’ll need to open this one in your browser to find out, as alas, I could not avoid the dreaded “Post too long for email”!

Austen Math 101

Jane Austen, arguably the greatest novelist of all time, was the author of six marriage-plot comedies of manners published between 1811 and 1817: Sense and Sensibility, Pride and Prejudice, Emma, Mansfield Park, Northanger Abbey, and Persuasion. There is rampant dispute as to how to read them. “The people who read Austen for the romance and the people who read Austen for the sociology are both reading her correctly,” Louis Menand argues, “because Austen understands courtship as an attempt to achieve the maximum point of intersection between love and money.”

Menand’s vaguely mathematical binary is directionally accurate but insufficiently sophisticated. Austen is absolutely a marital maximizationist, but her calculations have far greater dimensional depth. As such, neither the die-hard romantics nor sociologists are reading her correctly; they are equally mistaken. Over- or under-weighting any single dimension of Austenian courtship maximization amounts to a fundamental misunderstanding of what she most cunningly gets:

Austen understood status—ahem, station; that its shoring up is hardly superficial. The intrigue of the marriage plot springs not just from uncertain affection—“will they fuck”—but the balance of such possibilities with a complex and often competing set of considerations. Status questions, basically, though to the standard socioeconomic strains I would add, particularly in Austen’s case, that of moral status. Alas, fuckability is a kind of status, too.

The Austen Math model more or less directly follows my original offhand vision, ranking all of Austen’s single men across four weighted dimensions—fortune, morals, manners, and fuckability—to develop secondary insights, calculate their individual total status, and analyze their relative marital desirability. The heroines, in turn, are judged by their dimensional weighting (and to what extent it shifts over time) versus the Austenian baseline. In other words: they are judged on the soundness of their judgment. The better a heroine is at Austen Math herself, the more virtuous she is deemed.

And what of love per se? Even the most sophisticated mathematical models are simplified phenomenological representations. Indeed, this is the purpose of models. I’d argue love is largely represented indirectly by a proprietary mix of the various dimensions—but I do not claim to capture all of Austen’s complexity, let alone any universal truths.

Methodology*

I. Dimensional raw scoring of single men

Each single man is evaluated on each of the four primary status dimensions of FORTUNE, MORALS, MANNERS, and FUCKABILITY using a whole-number score of 1 to 6, one being low and six high, based on textual analysis by yours truly.

My definitions are as follows, with help from Merriam-Webster (MW):

By FORTUNE (n), I mean “riches; wealth,” in line with MW 1.2, “a man of fortune.”

By MORALS (n), I mean both “ethics” and “modes of conduct,” per MW 2.2a-b, in the context of Christian Regency norms without blind deference to them.

By MANNERS (n), I mean personal bearing, air, deportment, style, etc., running the gamut of MW 1a-e, again filtered through a critical Regency lens.

By FUCKABILITY (n), admittedly not in MW, I mean sexual desirability, predominantly but not exclusively based on physical attractiveness, also including demonstrable charm, wit, and je ne sais quoi.

The six-point scale both allows for sufficient differentiation across Austen’s six novels and forces non-neutrality.

II. Austenian primary status weighting (baseline)

The four primary dimensions predict total status via uneven weight distribution, in alignment with the hierarchy of Austen’s values as I have long understood them:

MORALS - 40%

FORTUNE - 30%

MANNERS - 20%

FUCKABILITY - 10%

for a total of 100%.

The formula to calculate total estimated Austenian status is a basic SUMPRODUCT: D1*W1 + D2*W2 + D3*W3 + D4*W4, where D=dimensional raw score and W=Austenian weight.

III. Secondary dimension calculations

Each pair of congruous primary dimensions yields insights into a secondary dimension. At the intersection

of FORTUNE and MORALS is WORTH,

of MORALS and MANNERS is CHARACTER,

of MANNERS and FUCKABILITY is AFFECT,

and of FUCKABILITY and FORTUNE is ELIGIBILITY.

Secondary dimension calculations may be performed either via weighted or unweighted averages of their raw inputs to harness insights inclusive or exclusive of Austenian status bias, respectively.

Note the secondary dimensions get closer to viscerally lovable personal attributes—character, affect—but would be harder to directly quantify themselves (e.g.: worth is more subjective than fortune).

IV. Heroine dimensional weight variance

Each heroine is evaluated on the difference between her hierarchy of the four primary status dimensions (again per my textual analysis) and Austen’s. Like in the Austenian baseline, the heroine’s top-priority dimension is weighted 0.4, with -0.1 for each subsequent priority.

The formula for dimensional weight variance is: |W1-H1|+|W2-H2|+|W3-H3|+|W4-H4|, where W=Austenian baseline weight and H=heroine weight. I use this absolute-value “spread” calc over true squared variance for its simplicity, clarity, and sufficiency given the small size of the data set. The score will fall between 0 and 0.8 in increments of 0.2, and can be roughly interpreted as follows with regards to the heroine’s judgment:

0 - Unimpeachable

0.2 - Sound

0.4 - So-so

0.6 - Precarious

0.8 - Misguided

I.e., the lower the score, the better her judgment. In some cases, heroines’ dimensional values change over the course of the novel, in which cases I calculate both starting and ending hierarchy for comparison to estimate their development.

*Feel free—nay, encouraged—to quibble with any of this. We are here first and foremost to have fun, and banter is damn close to my definition of it.

Credentials

While admittedly an amateur Austen scholar, I am the daughter of a doting professional one—and a professional novelist and management consultant myself (see: Portrait, patents). My undergraduate degree is in English and my graduate an MBA: a thoroughly Austenian compromise. Her voice has been inseparable from that of my own conscience since I was ten years old.

Part 3: Emma

“Emma Woodhouse, handsome, clever, and rich, with a comfortable home and happy disposition, seemed to unite some of the best blessings of existence; and had lived nearly twenty-one years in the world with very little to distress or vex her”—yet, anyway. Emma’s governess turned bosom friend, Miss Taylor, soon becomes Mrs. Weston, marrying their amiable neighbor—a great match (and one Emma flatters herself to have made), except in taking her away from Hartfield, the ever-ailing Mr. Woodhouse, and Emma herself.

Into the void of female companionship steps Harriet Smith, the beautiful and kind, if none too bright, “natural daughter of somebody.” Not everyone approves—namely, Mr. George Knightly, a longtime family friend; the area’s largest landowner and elder brother to Emma’s sister’s husband. He thinks Emma’s company would be better spent with Jane Fairfax, her equal in intelligence and education. But Emma is undeterred, eager to be of use. She dissuades Harriet from accepting the proposal of Mr. Robert Martin—a solvent farmer, but not a gentleman—in favor of encouraging Highbury’s handsome young clergyman, Mr. Philip Elton. Mr. Elton misinterprets these efforts to great mutual humiliation, unsuccessfully proposing to Emma herself.

It’s a blow, to be sure, but all is not lost: Mr. Elton absconds to Bath just as Mr. Weston’s son from a prior marriage arrives. Adopted by his wealthy uncle and aunt after the first Mrs. Weston’s death, Mr. Frank Churchill seems everything a gentleman should be:—the only sort of man who might tempt a woman for whom marriage offers little temptation at all.

The single men

Mr. George Knightley; Mr. Robert Martin; Mr. Philip Elton; Mr. Frank Churchill

Fortune

As master of Donwell Abbey, Mr. Knightley is the wealthiest and most important man in the area, though Austen uncharacteristically does not provide his income. What we have instead: that “The house was larger than Hartfield” (though the wealth of the families more on par); that he frequently engages in discussions as to the betterment of his land and the livelihoods dependent on him; and a curious, almost throwaway line about “little spare money” in a list of reasons for his infrequent carriage usage. I am inclined to interpret this last clue as pertaining strictly to cash flow in the face of prudent reinvestment—and give Knightley 5/6.

Mr. Martin is a young Donwell tenant, renting Abbey-Mill farm with his mother and sisters. While responsible and prosperous enough to receive Mr. Knightley’s concurring advice to marry, he belongs to a fundamentally different class. 2/6.

Mr. Elton falls between them—“for though the vicarage of Highbury was not large, he was known to have some independent property.” But while comfortable and well-attuned to his financial interest, Elton is still a clergyman, and scores 3/6.

And then there is Frank Churchill; a puzzle, as we shall see, in more way than one. As his uncle’s heir, he is set to inherit Enscombe, a Yorkshire estate of unspecified handsome income. We never get to see it up close, but I get the sense it’s on the order of Donwell Abbey, not quite Pemberley. If the estate was already his, I’d give him a five, but as the heir apparent—and a particularly beholden one at that—Frank gets 4/6.

Morals

Knightley and Martin may be master and tenant, but they have similarly sterling morals. The former is the novel’s guiding light; a source of wisdom and beacon of generosity, which the latter smartly consults without unduly relying on. Knightley in turn commends Martin’s “good sense and good principles,” going so far as to claim near the novel’s end: “His rank in society I would alter if I could, which is saying a great deal I assure you, Emma.” Their mutual respect does mutual credit; both get 6/6.

Elton and Churchill prove more challenging to rate.

The clergyman’s primary sin takes shape in the form of his mercenary choice of wife. I’m almost inclined to evaluate his morals on terms akin to the heroine model. Specifically: in his deprioritization of hers. For Mr. Elton’s associative guilt and otherwise moral unremarkability: 3/6.

Frank Churchill’s false encouragement of Emma to cover his secret engagement is tricky to parse, his failures of morals and manners being so closely entwined. Emma bears the brunt of his deception in her unconsciousness of it, while Jane suffers more from his outward behavior in her complicity. Ultimately, the former, moral sin weighs heavier. That Emma emerges unhurt and seems to entirely forgive him should not tempt us to let Frank off the hook—Mr. Knightley sure doesn’t. 3/6 for morals . . .

Manners

. . . and 4/6 for manners, an average of erratic data points. Frank’s manners are quite often the picture of elegance. But his demeanor is periodically marred by ill humor under the weight of his secret—not to mention “the unfortunate fancy for having his hair cut”!

Elton’s manners are similarly variable, but on less empathetic grounds. I can only think him the primary source of the “smooth guy who treats service staff poorly” archetype. While adept at ingratiating himself, his warmth is tainted by obsequiousness—and in its absence he is downright rude. Nowhere is this more apparent than in his refusal to dance with Harriet at the Crown ball. Mr. Darcy may be able to pull himself above average in the aftermath of such a crime—but Mr. Elton cannot. 3/6.

“In another moment a happier sight caught her;—Mr. Knightley leading Harriet to the set!” And he dances extremely well. Yes, Mr. Knightley embodies every courtesy, every commanding elegance at which Elton merely postures. His conduct is cheerful yet dignified, commanding without being proud; his air “remarkably good.” “You might not see one in a hundred with gentleman so plainly written as in Mr. Knightley,” Emma says.—For his one-percent manners: 6/6.

Mr. Martin proves the hardest to score. For while his manners are polite, they are unpolished. “I am sure you must have been struck by his awkward look and abrupt manner,” Emma rebukes Harriet, “and the uncouthness of a voice which I heard to be wholly unmodulated as I stood here.” His temperament, as Knightley regularly points out, does him credit—but cannot outweigh the ingrained mores of his station. 2/6.

Fuckability

Poor Robert Martin isn’t good-looking either: “Oh! not handsome—not at all handsome,” even Harriet admits. “I thought him very plain at first, but I do not think him so plain now.” Since he gets the girl anyway: 2/6.

The other three are handsome, however—

Frank Churchill emphatically so: “he was a very good looking young man; height, air, address, all were unexceptionable, and his countenance had a great deal of the spirit and liveliness of his father’s; he looked quick and sensible.” He still doesn’t deserve Jane Fairfax, but at least she draws this benefit: 6/6.

Mr. Elton is nearly as sexy and he knows it. Emma finds “a want of elegance of feature which she could not dispense with,” but considers him more than fit for very-pretty Harriet. 5/6.

What to do with Mr. Knightley? On the one hand, he is on the dreaded “wrong side of five-and-thirty”—but Austen mercifully describes this state very differently in Emma than she does in Sense and Sensibility. Knightley is granted “a great deal of health, activity, and independence,” and while there is little mention of his looks directly, in comparing him to Frank Churchill more broadly, Emma—who is not insensible to appearances—“saw that there never had been a time when she did not consider Mr. Knightley as infinitely the superior.” Yes, there is that line, cringeworthy to modern ears, about him loving her since she was thirteen. But this longstanding intimacy also underpins their badinage—the delicious challenge of his wise, well-matched mind! Is it all a little “hot for teacher”? Yes—but, still hot. I cannot in good conscience give him anything less than Frank Churchill! Mr. Knightley is eminently fuckable. 6/6!

Secondary dimensions & insights

Graphing their raw scores and calculated unweighted secondary dimensions, we see some new shapes as well as a familiar one:

We’ll get to Knightley’s giant “O” in a moment. First, take a look at the other three. Elton is mathematically the poor man’s Frank Churchill—of course Emma, having failed to match Harriet with Elton, sets her sights on Frank once she is confident in her own platonic feelings for him! Robert Martin, meanwhile, forms a nearly inverse shape.

The secondary characteristics in particular tell the story here: a visible equivocation between Austen’s respect for the established tenets of Regency status and critique of its obvious inequities. Frank Churchill and even Elton blow Robert Martin out of the water in affect and eligibility—there is no question who society deems more valuable, and Austen would never ignore it. And yet! Mr. Martin ekes both of them out in terms of worth and character, buoyed by his moral superiority.

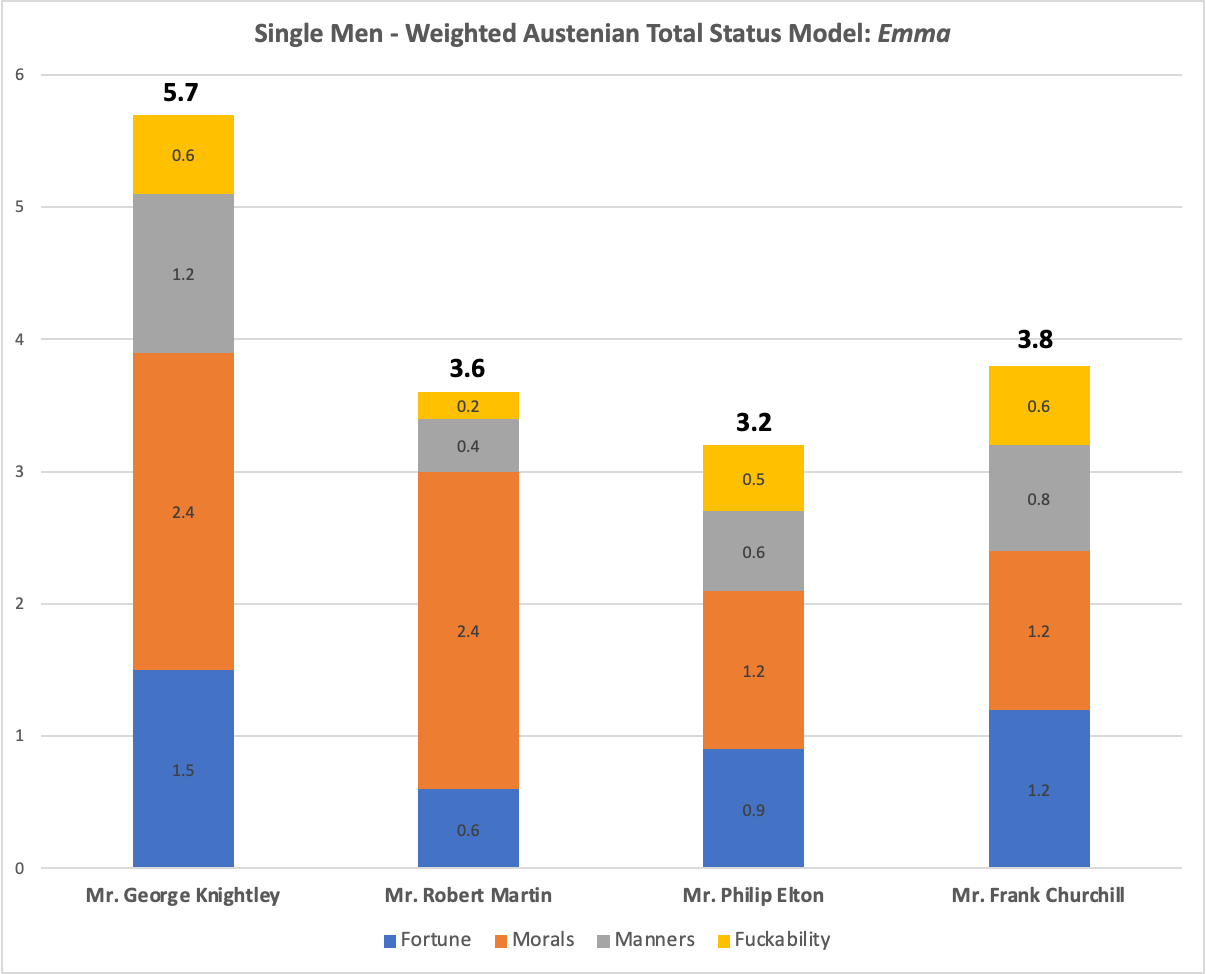

Weighted Austenian Total Status Model

Looking at the weighted model, we see their total scores predictably converge toward the model average (3.5).—Excepting Mr. Knightley, obviously, who earns a whopping five-point-seven:

Congratulations are in order for

, who correctly predicted “that Knightley will actually beat Darcy’s score” (5.6).Prediction itself is key to Mr. Knightley’s triumph. The character most similar to him in the novels analyzed thus far is not Mr. Darcy. It is Elinor. And I would argue that Knightley speaks for their author to an even greater extent. For while Elinor is nearly as shocked as the rest of her family by several twists of character and fate, Knightley is forever foreseeing them.

Mr. Knightley’s prophetic insights include: that Emma and Harriet’s intimacy spells mischief; that Elton “does not mean to throw himself away”; that Frank Churchill is less upstanding than he seems; that Robert Martin is a good match for Harriet; that Emma has gravely wronged Miss Bates at Box Hill; and above all, long before Emma realizes it, “that Mr. Knightley must marry no one but herself!” There are probably more, but I think I have proved my point. On top of it: for all his overwhelming rightness, Mr. Knightley can admit when he is wrong. Here is Emma, with him responding:

“I do own myself to have been completely mistaken in Mr. Elton. There is a littleness about him which you discovered, and which I did not: and I was fully convinced of his being in love with Harriet. It was through a series of strange blunders!”

“And, in return for your acknowledging so much, I will do you the justice to say, that you would have chosen for him better than he has chosen for himself.—Harriet Smith has some first-rate qualities, which Mrs. Elton is totally without. An unpretending, single-minded, artless girl—infinitely to be preferred by any man of sense and taste to such a woman as Mrs. Elton. I found Harriet more conversable than I expected.”

His high score is qualitatively justified. The man is willing to move to Hartfield! (Darcy would never!) Put your hands up for Mr. Knightley!

The heroines

Miss Emma Woodhouse

Three of Austen’s novels are named for human abilities, two for properties, but only one for a person. Harriet’s judgment merely follows Emma’s, while Jane Fairfax’s reserve largely precludes analysis. As a heroine, Emma stands alone.

In her handsome rich cleverness, the Austenian character to whom Emma is probably most frequently compared is Mr. Darcy. But to the extent that the novels are connected, the heroine model suggests Austen is less interested in asking “what if Mr. Darcy was a woman” than “what if Elizabeth Bennet was rich?”

Emma’s dimensional priority arc traces Elizabeth’s, with Mr. Knightley gradually guiding her judgment from 0.4 - So-so, to 0.2 - Sound.

The moral core is there from the start: Emma is unfailingly kind and patient with her father, a thoughtful hostess, a well-meaning friend, and unoccupied with her own considerable beauty. As Mr. Knightley says, “her vanity lies another way.” Namely: in meddling, and on the basis of misguided status prioritization down the list. She overvalues manners and appearance in other women as well as men, and undervalues money—blinded of its importance precisely in her own abundance, tying status disproportionately to affect instead.

Emma’s greatest blunders, foretold by our right hero, Mr. Knightley, nearly all tie to this misconception. She thinks reforming pretty Harriet’s manners will outweigh her penniless illegitimacy for Elton—then the same for his superior, Frank. Likewise, Emma’s mocking of Miss Bates is far less a failure of manners themselves than a misjudgment of fortune’s importance:

“Oh!” cried Emma, “I know there is not a better creature in the world: but you must allow, that what is good and what is ridiculous are most unfortunately blended in her.”

“They are blended,” said he, “I acknowledge; and, were she prosperous, I could allow much for the occasional prevalence of the ridiculous over the good. Were she a woman of fortune, I would leave every harmless absurdity to take its chance, I would not quarrel with you for any liberties of manner. Were she your equal in situation—but, Emma, consider how far this is from being the case. She is poor; she has sunk from the comforts she was born to; and, if she live to old age, must probably sink more. Her situation should secure your compassion. It was badly done, indeed!

Emma repents mightily of her behavior, visiting Miss Bates the next morning, and by end of the novel, fortune fully assumes its proper, Austenian place in her judgment hierarchy. She still can’t quite see eye-to-eye with Mr. Knightley on either Frank Churchill or Robert Martin, disproportionately forgiving the handsome face—like Elizabeth, letting manners fall below fuckability. But with Mr. Knightley becoming Mr. Nightly, there is hope she may ascend to unimpeachability yet.

Other misc. notes from this read:

The novel is as Girardian as I remembered it being: “Emma realizes she loves Mr. Knightly only when Harriet’s confesses to.”

Very funny amount of appreciation for the post-office!

More hair! Also, the fuss made over Frank Churchill’s London hair cut is not just a riot—it births maybe the best paragraph of the novel:

“I do not know whether it ought to be so, but certainly silly things do cease to be silly if they are done by sensible people in an impudent way. Wickedness is always wickedness, but folly is not always folly.—It depends upon the character of those who handle it. Mr. Knightley, he is not a trifling, silly young man. If he were, he would have done this differently. He would either have gloried in the achievement, or been ashamed of it. There would have been either the ostentation of a coxcomb, or the evasions of a mind too weak to defend its own vanities.—No, I am perfectly sure that he is not trifling or silly.”

Middlemarch, which has been having a moment on Substack recently, not only owes a tremendous debt to Austen in general, but to Emma specifically. Emma is also the story of Highbury. Of the Coxes and the Coles; of Mrs. Goddard, William Larkins, and the ever-cited Mr. Perry.

NEXT UP, “Austen’s most complex novel,” Mansfield Park, which I might be more excited to reread than any other. Will Fanny Price offer greater appeal in the waning months of my thirties than she did in my youth? Will the Crawfords seem as sexy? TBD!

Until next time, and with great thanks for reading (I have been deeply chuffed by Austen Math’s reception!),

I remain,

Yours—

ANJ

Excited for the evaluation of Henry Crawford! I have always had a decided partiality for him; for my money, there is nothing like a short charismatic man troubled by his conscience. I fear what that says about my Austenian judgement score.

Very much enjoying these roundups of the characters, and the whole formulation of Austen Math. Thank you!