Status (part 1)

a diachronic canon

I. Introductory

I’m calling this “a diachronic canon,” with emphasis on the indefinite article, after

’s definition and usage of diachronicity and ’s of canon. Their combination marries the antithetical twin desires underpinning my will to write: for metamorphosis and for permanence. For the Joycean synthesis of Ovidian apotheosis and the Eliotic “historical sense,” I might have put it as an undergrad. Now: I want to leave diamond-like works of beauty and truth in my wake, without my mind ever crystallizing in them.Like Batuman, I’ve been interested in a cluster of related ideas for a long time. Collen uses their -2021 synthesis in The Portrait of a Mirror to help develop his expansive conception of canon:

There is another way canon can be approached: as a mine of ideas, allusions, and referents which can inform and embellish new works and lend structure and shape to them. One of the best examples of this way of approaching the canon is exhibited in A. Natasha Joukovsky’s novel The Portrait of a Mirror. Her basic plot—rich people having love and relationship troubles—owes a considerable debt to Austen and to Middlemarch, a debt which Joukovsky acknowledges. But her repertoire of allusions goes much farther than that. [. . .] it’s a highly self-referential book, with widely-spaced passages being almost identical, mirror-image reflections of each other. As such it becomes its own canon.

Is my concept of “a diachronic canon” tautological? I prefer recursive. To Batuman(Berlin’s)’s “hedgehog-fox” that thinks one big many-layered thing I’ll add the image of the Matryoshka doll: ideas and writing nesting over time, enveloping their previous iterations; each layer dependent yet distinct.

II. Mother Doll

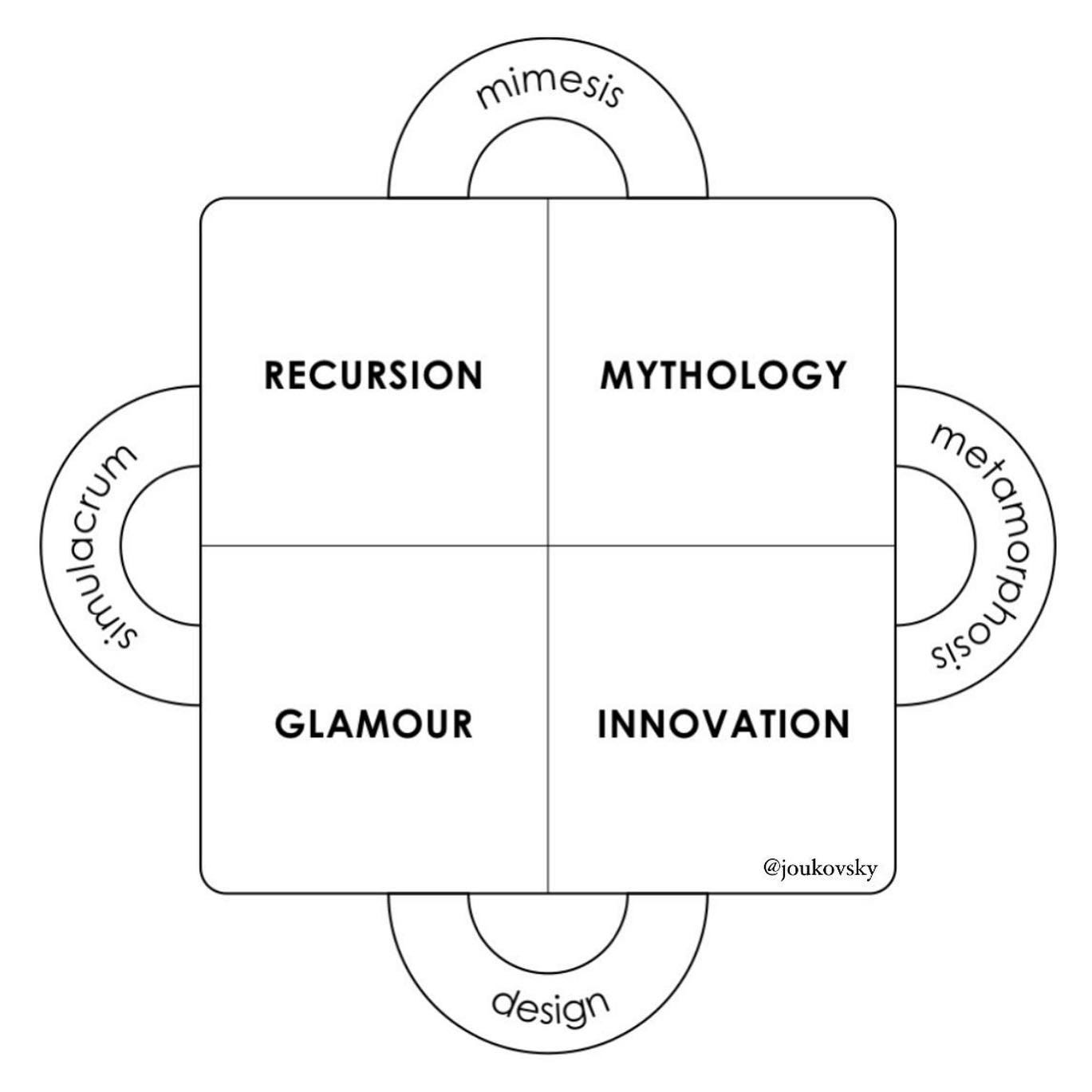

While I was writing Portrait, I made another framework trying to synthesize its canonesque themes, inseparable from the nexus of my interests overall. Longtime readers may have seen it before:

If I was building this today, post exposure to René Girard (a wonderful “adventure” by way of Portrait, “dictating [my] further fate and movements”—more on this in part 2), I would have probably swapped “mimesis” and “simulacris,” but its durability with adjustment is sort of my (Batuman’s) point. I was so excited about this framework when I first made it in 2015-16 that I created the precursor to my author website for the express purpose of sharing it (full-on deck no longer featured, but still viewable!). When I talk about Portrait’s “thematic architecture” in interviews, this framework is what I am talking about.

I only recently, in the process of writing my new novel, realized it was missing something crucial: the psychosocial why underpinning it all. “Collectively, this framework brings together fundamental human cognitive survival mechanisms we employ in our attempt to understand, connect, and shape our world,” I tried to summarize in the deck—which isn’t strictly wrong per se, but it’s clunky; still more an expression of what. Why did I care so much about this framework? Why should anyone else? I struggled to express this outside of fiction. Hence the trouble I had in titling it, my shitty branding (“framework2,” lol). Hence, too, the understandable dearth of direct reciprocal interest.

But I finally have a hypothesis. The hedgehog theme to rule my foxes? The “human cognitive survival mechanism”? It’s status—which rather explains my literary obsession with it, the canon of psychosocial threads running through quite useless—class, leisure, sprezzatura, snobbism, games, incentives, wealth, fashion, branding, arms races, collective action problems &c. &c. &c.

Recursion, innovation, mythology, and glamour are recurrent phenomenological effects of these psychosocial threads, of our various pursuits of status. Mimesis, metamorphosis, design, and simulacra are recurrent strategic mechanisms of its pursuit in art and life. But status is why. Status is the hedgehog. Status is the mother doll.

How did it take me so long to see it? My blindspot’s in the center of the mirror, like everyone else’s. And unlike with narcissism, which I’m now inclined to think of as simply an imbalanced and particularly virulent status strategy, the broader umbrella lacks a specific myth to cling to—not to mention a myth like Narcissus, a myth of dazzling beauty, moral and mortal danger, and millennia of canonical artistic significance.

Status is embedded more broadly, for starters in the Greco-Roman caste system—Olympians, Titans, minor gods, nymphs and their ilk, heroes, mere mortals. But being everywhere is often very like being nowhere, and we Americans tend to be uneasy with the concept of status itself; to house a deep, often subconscious embarrassment born simultaneously from the sense its endurance amounts to a kind of national failure and its taboo’s ironic tendency to uphold the status quo.

III. Baby Peacock

Status is the mother doll. At least it is for The Portrait of a Mirror. But in another sense, it’s also the kernel. The “basic plot” of Portrait—“rich people having love and relationship troubles”—and the debt to Austen in particular is only “basic” in a foundational sense.

Austen understood status—ahem, station; that its shoring up is hardly superficial. The intrigue of the marriage plot springs not just from uncertain affection—“will they fuck”—but the balance of such possibilities with a complex and often competing set of considerations. Status questions, basically, though to the standard socioeconomic strains I would add, particularly in Austen’s case, that of moral status. Alas, fuckability is a kind of status, too.

As a consultant (sorry), I can’t help but envision all of Austen’s single men plotted in a multi-dimensional status model based on fortune, morals, manners, and fuckability with carefully calibrated weights; the heroines judged on the basis of their strategic analyses. “I'm sure some of you might say strategy is immoral” (Lauren Oyler, Fake Accounts), but can this be true when Austen weighs moral status so highly? And then Robert Sapolsky makes a pretty compelling case against free will itself—that we’re “biological machines,” our feelings of feelings “a confusing, recursive challenge.”

But I’m getting ahead of myself. At ten years old, reading Jane Austen with my father, I was not yet thinking about free will. But I was thinking about status strategy and optimization, even if I wouldn't have called it that. I understood the precarity of the Dashwoods’ circumstances, the Mr. Collins Problem (entail but doofus); the chasm between Harriet and Emma’s stations and the latter’s social blunder in ignoring it. Provided you got her cunning irony and could parse the implications of different carriages (reading with an expert in the period who regularly taught her novels helped), Austen forthrightly addressed the status factors of such obvious import the adults around me tended to downplay even as they subtly incentivized my future heroinic success: to be pretty but not vain, smart but not threatening—the whole America Ferrera Barbie speech, basically.

The criticality of status as a calculation to be weighed with and against interior conscience is the kernel on which my life and art has unfolded in a diachronic canon. The matryoshka doll image is a little humble for me personally, however. Let’s go with a peacock, which in addition to being more on-brand, is less taxing on my limited graphic design skills:

IV. Nested insights

(Do peacocks nest? I have no idea. Please tell me if you know.)

1.

The structure of a diachronic canon supports my longstanding sense there is generally no reason to be embarrassed by one’s juvenilia. Juvenilia is the peachick around which more sophisticated work achieves its shape. (Batuman’s written about this, too, though I am having trouble finding the exact quote—something to the effect of: save what you write when you’re young, you might find it interesting later.)

An example: I went back to “Seven Types of Irony in Jane Austen’s Novels” to see how I’d described the Emma/Harriet dynamic at 18 and discovered I was also already thinking about narcissistic incongruities and blind spots:

The basic irony of Emma’s disagreeable encounter with Mr. Elton centers on the discrepancy between each character’s place in society and their matrimonial expectations. Emma is flabbergasted that Mr. Elton, a mere clergyman, would have the audacity to ask for the hand of someone of her wealth and class. However, she is also flabbergasted that Elton would not be interested in Harriet, an illegitimate child from an unknown family who is as much beneath his class as Emma is above it.

The next irony is obviously that Emma, who is so very much aware of class distinctions in her refusal to Mr. Elton’s proposal, would not only further, but ignite Harriet’s interest in a man with whom she has no chance. This is not to say that Emma should have accepted Mr. Elton, who would be as undesirable a match for her as Harriet would be for him. The irony is that Emma’s good understanding of what would be advantageous for her so strikingly fails to apply when she imagines that Mr. Elton would be undoubtably attracted to Harriet.

2.

The concepts of diachronicity and canon are (recursively!) evident in not only structure but content, in my undergraduate obsession with literary revision. How myths become myths; the Modernists’ creative processes and palimpsests; Joyce’s additive approach vs. Eliot’s subtractive one. Here’s how I put it in the author questionnaire my publisher had me fill out for Portrait in 2020:

When I read Ulysses the semester after taking "Art & Myth," my mind was primed for its allusive fragmentism. I went on to argue in my undergraduate thesis that Ulysses and The Waste Land became “the twin pillars of Modernist prose and poetry” by returning to myth in formally innovative ways. My focus was the historical lives of the documents themselves, deciphering their palimpsests, trying to figure out precisely how Joyce and Eliot had managed to join Homer and Virgil and Ovid as literary immortals so late in the game. Here's an excerpt from the contemporaneously-written abstract (2008):

"In his essay “Tradition and the Individual Talent,” T. S. Eliot argues that the synthesis of the timeless and the temporal, of the traditional and the original, is essential to the creation of canonical, lasting literature. I suggest that Eliot’s theory reflects the creative dilemma of the Modern artist in particular, and his precarious place in history. The “burden of the past,” or creative anxiety due to the greatness of prior accomplishments in literature, already weighed heavily upon the Romantics, and it only increased in the early years of the twentieth century. James Joyce’s epic novel Ulysses offered a possible solution to this problem: to revive and revise myth, to create ex materia rather than ex nihilo—a solution that greatly influenced Eliot himself, particularly in his magnum opus, The Waste Land.

I argue that Ulysses and The Waste Land, both published in 1922, have become the “twin ‘myths’ of Modernism” and the twin pillars of Modernist prose and poetry respectively, due to the similar juxtaposition in these works of the return to myth and the synthetic aesthetic—a new, distinctly Modern style of allusive fragmentism. William B. Worthen dubs The Waste Land “Eliot’s Ulysses”—and in many ways, it is. But the means by which Joyce and Eliot arrived at a similar convergence of tradition and originality varied widely, and in works so similarly hyperconscious of history, the historical lives of the documents themselves are of particular critical interest."

Only in retrospect did I awaken to the full selfishness of this exercise—that the real question I was trying to answer was how to channel my own literary ambitions to their fullest effect. It wasn't until 7 or 8 years later, when I started outlining the novel that would become The Portrait of a Mirror (its working title was "Recursion"), that I realized I'd given myself an explicit roadmap. I wanted to follow the "mythical method" Eliot so admired in Ulysses; to try to capture the present moment by way of the Western tradition in a way that would appeal to a contemporary audience with a general attention span of 140 characters. The story of Narcissus and Echo, I thought, was the myth for the job.

3.

I finally have a simple response to that vexing perennial question posed to novelists: how did you do it? Well, by being me.

If this has an unsatisfying whiff, I’d argue that’s because when people ask how did you do it? what they’re often trying to ask is how do I do it? If the latter is the real question, I do have specific tips—but poring over my diachronic canon isn’t one of them. It’s so specific, so unrepeatable; so fundamentally based on luck.

4.

Perhaps the publication of my debut novel at 35, Dante’s“midway on the journey of our life”—around which I anchored my mid-Portrait reflection—is a coincidence. I certainly hope to live beyond 70, and have the good fortune to statistically expect it. But it feels meaningful, and I’m back to Sapolsky’s “confusing, recursive challenge”—more properly a topic for my post-Portrait era, so this is where I’ll pause.

Part 2 TK will cover the thematic shift with my new novel toward rarity, probability, prophesy, luck—but I’m not sure yet what exactly it will look like, or when it will go out. To reassure my agent: first I’m trying desperately to finish the novel itself! It’s almost done.

Thanks for reading,

Natasha

All writers should do this sort of self-analysis and graph-making, because it's fun!

Peahens nest on the ground or occasional in a tree.