This is the second of a two-part post; you can find part one here.

Of the five great novelists Girard discusses in DDN, his analysis of Proust astounded me most. Again, you don’t need to have read Remembrance of Things Past to appreciate it (I haven’t, though certainly plan to now). That the Faubourg Saint-Germain is a historically aristocratic district in Paris is the only context required.

The facile criticism of Proust Girard outlines in the process of defending him feels extraordinarily contemporary—it’s the same jibe we see levied at some point against nearly every work of art today featuring a primarily patrician milieu. Change only the proper nouns and the following could be a response to, say, a bad review of Succession:

Proust is accused of confining himself to too narrow a milieu but no one recognizes and denounces that narrowness better than Proust. Proust shows us the insignificance of “high society” not only from the intellectual and human angle but also from the social point of view: ‘The Members of the fashionable set delude themselves as to the social importance of their names.’ Proust pushes the demystification of the Faubourg Saint-Germain much further than his democratic critics. The latter, in fact, believe in the objective existence of the magic object. Proust constantly repeats that the object does not exist. ‘Society is the kingdom of nothingness.’ We must take this affirmation literally. The novelist constantly emphasizes the contrast between the objective nothingness of the Faubourg and the enormous reality it acquires in the eyes of the snob.

The novelist is interested neither in the petty reality of the object nor in the same object transfigured by desire; he is interested in the process of transfiguration . . . What fascinates Proust is that the snob can mistake the Faubourg Saint-Germain for that fabled kingdom everyone dreams of entering.

Proust’s Faubourg Saint-Germain is Logan’s office at Waystar Royco. In Gossip Girl, it’s the social cluster huddled on the front steps of the Met. In each case, the snob mistakes society for heaven; the snob mistakes the metaphysical desire to be another—to be a god—with the material desire of gaining entry to the inner sanctum. With this mistake, the snob is inevitably disappointed by material achievement. The inner sanctum is metamorphosed, its glamour stripped away. Hence at the beginning of The Portrait of a Mirror, Wes’s disillusionment with his apartment:

[H]e hated the loft for all the reasons he’d bought it, and hated his wife for the reasons he’d married her. His greatest affirmations were drawn from the same well as his personal disappointment, and his brain boiled with the specific kind of regret paradoxically associated with success.

In retrospect, I probably shouldn’t have used the word “paradoxically”; Wes is adhering to the predictable mechanics of desire. Still, it is precisely in the seemingly paradoxical disconnect between metaphysical disappointment and material success that snobbism presents an unusually salient opportunity to understand these mechanics. As Girard puts it: “The snob seeks no concrete advantage, his pleasures and sufferings are purely metaphysical. Neither the realist, nor the idealist, nor the Marxist can answer the novelist’s question.”

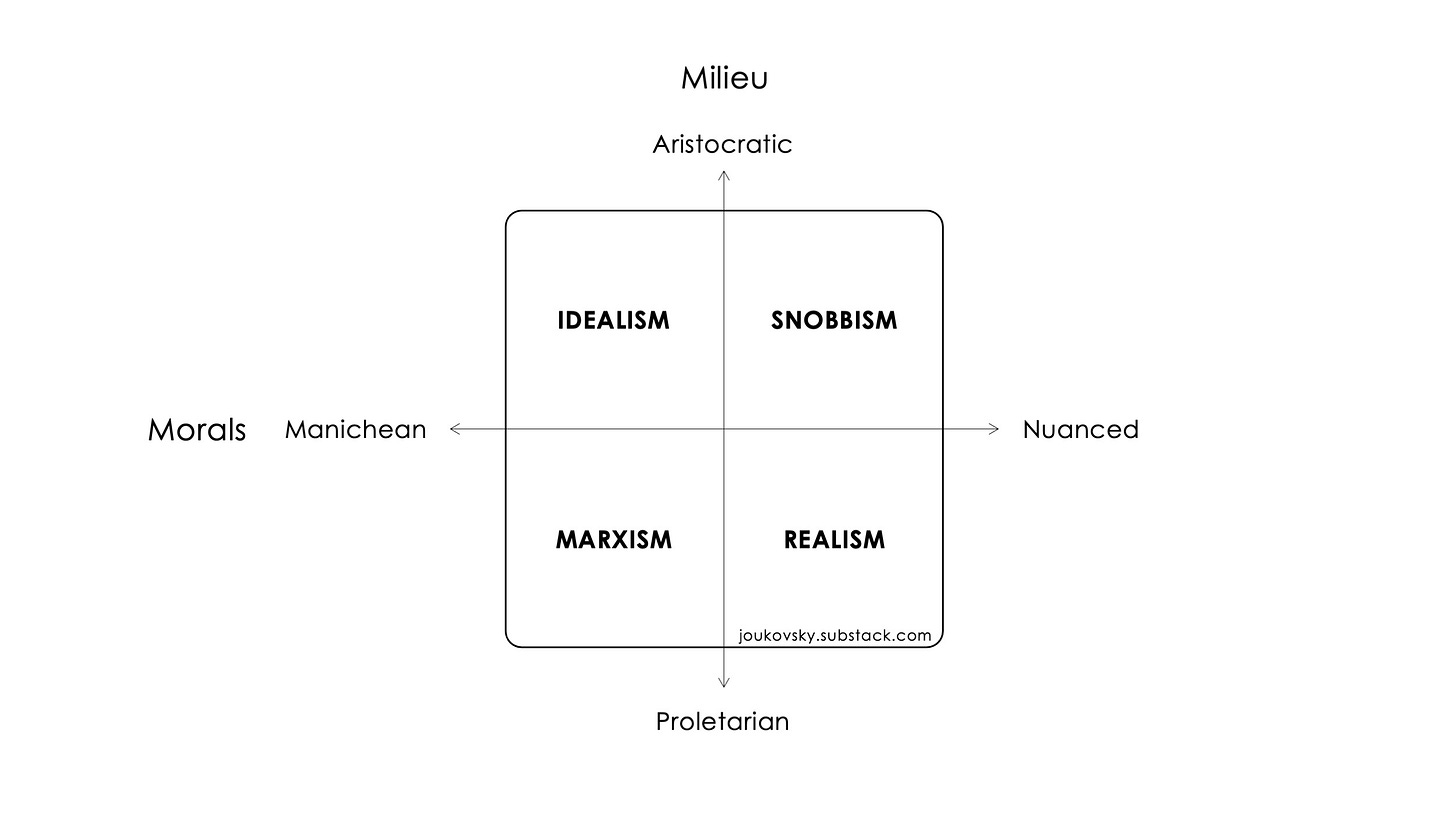

I’ve been trying for weeks to zoom out and visualize snobbism in this broader artistic context, and the 2x2 below is my best approximation. Think of it kind of like Vulture’s “approval matrix” in that you might plot various cultural artifacts on it graphically, but minus any value judgment:

When I ran this chart by Trevor Cribben Merrill, he summarized it perfectly, using a metaphor I can get behind: “in idealism you renounce the bottle of wine; in Marxism you smash it; in realism you savor it; in snobbism you flaunt it.”

Idealism & realism

The idealist is above material desires, and purely devoted to pursuing metaphysical goals—namely, the triumph of “good” over “evil.” Such dualist narratives dominate a wide swath of popular genres, from chivalric romance to space opera. There’s little to no tension between material and metaphysical desires, because material desires are irrelevant. Characters rarely eat or drink (unless ceremonially, and thus to a higher purpose)—and they never have to pee.

Conversely, the realist depicts the everyday material world as it is. My mind goes straight to the paintings of Courbet and Millet. The morals are nuanced, but the material needs are clear. Metaphysics are relegated to the background, as wheat literally takes center stage:

I’m reminded now too of the passage in Antoine de Saint-Exupéry’s memoir Wind, Sand and Stars about the incomparable pleasure of eating half an orange while stranded in the desert, after crashing his plane:

Stretched out beside the fire I looked at the glowing fruit and said to myself that men did not know what an orange was. “Here we are, condemned to death,” I said to myself, “and still the certainty of dying cannot compare with the pleasure I am feeling. The joy I take from this half of an orange which I am holding in my hand is one of the greatest joys I have ever known.”

I lay flat on my back, sucking my orange and counting the shooting stars. Here I was, for one minute infinitely happy.

Talk about savoring something! Saint-Exupéry’s deprivation borders on ecstasy in its entrée to the purely material.

Marxism & snobbism

Marxism brings us closer to exposing the gap between material and metaphysical desire, and Girard has a lot to say about it:

The Marxist analyses of bourgeois society are more penetrating than most but they are vitiated at the outset by yet another illusion. The Marxist thinks he can do away with all alienation by destroying bourgeois society. He makes no allowance for the extreme forms of metaphysical desire, those described by Proust and Dostoyevsky. The Marxist is taken in by the object; his materialism is only a relative progress beyond middle-class idealism.

Proust’s work describes new forms of alienation that succeed the old forms when “needs” have been satisfied and when concrete differences no longer control relationships among men. We have seen how snobbism raises abstract barriers between individuals who enjoy the same income, who belong to the same class and to the same tradition. Some of the institutions of American sociology help us appreciate the fertility of Proust’s point of view. Thorstein Veblen’s idea of “conspicuous consumption” is already triangular. It deals a fatal blow to materialist theories. The value of the article consumed is based solely on how it is regarded by the Other. Only Another’s desire can produce desire. More recently, David Riesman and Vance Packard have shown that even the vast American middle class, which is as free from want and even more uniform than the circles described by Proust, is also divided into abstract compartments. It produces more and more taboos and excommunications among absolutely similar but opposed units. Insignificant distinctions appear immense and produce incalculable effects. The individual’s existence is still dominated by the Other but this Other is no longer a class oppressor as in Marxist alienation; he is the neighbor on the other side of the fence, the school friend, the professional rival. The Other becomes more and more fascinating the nearer he is to the Self.

The Marxists explain that these are “residual” phenomena connected with the bourgeois structure of society. Their reasoning would be more convincing if analogous phenomena were not observed in Soviet society. Bourgeois sociologists are only shuffling the cards when they claim, observing these phenomena, that ‘classes are forming again in the U.S.S.R.’ Classes are not forming again: new alienations are appearing where the old ones have disappeared.

Marxist policies (as well as more “realist” progressive ones) can ameliorate problems of “needs”—but cannot do the same for “wants.” Ironically, they even have the potential to exacerbate our metaphysical pain, because it is precisely sameness that drives the metaphysical desire to self-differentiate. We’re back to “Nothing highlights difference quite like homogeneity” here—and specifically: “Nothing highlights difference.” In Portrait, I wanted to test the boundaries of this nothingness (Dale and Diana’s relationship in particular is defined by “negative space”). If we cannot differentiate ourselves materially, we will try to do so based on nothing at all. This is the essence of snobbism, and why snobbist narratives disproportionately tend to expose the “romantic lie” of spontaneous desire. Here’s Girard again:

The snob desires nothingness. When the concrete differences among men disappear or recede into the background, in any sector whatever of society, abstract rivalry makes its appearance, but for a long time it is confused with the earlier conflicts whose shape it assumes. The snob’s abstract anguish should not be confused with class oppression. Snobbism does not belong to the hierarchies of the past as is generally thought, but to the present and still more to the democratic future. The Faubourg Saint-Germain in Proust’s time is in the vanguard of an evolution that changes more or less rapidly all the layers of society. The novelist turns to the snobs because their desire is closer to being completely void of content than ordinary desires. Snobbism is the caricature of these desires. Like every caricature, snobbism exaggerates a feature that makes us see what we would never have noticed in the original.

Girard takes this a step further, claiming “The novelist who reveals triangular desire cannot be a snob, but he must have been one. He must have known desire but must now be beyond it.” Which brings us to Sally Rooney’s latest novel.

Post-snobbism

Girard aside, I was always going to be interested in Beautiful World, Where Are You given its superficial mega-similarity to Portrait—four attractive, hyper-articulate Millennials falling in and out of desire and/or love with each other, etc. But there are also points at which Rooney’s characters, and in particular her Rooney-esque novelist Alice, channel Girard through and through.

“I just don’t care what they think about ordinary life or ordinary people,” Alice complains of the literary crowd, “Why do they pretend to be obsessed with death and grief and fascism—when really they’re obsessed with whether their latest book will be reviewed in the New York Times?” This line, basically destined to be quoted in the actual New York Times review of the book, shortly follows Alice’s somber promise that she’s “not going to get into another argument with [Eileen] about the Soviet Union, but when it died so did history,” and precedes an apology for bourgeois novels’ material shortcomings and her own post-snobbist confession: “My own work is, it goes without saying, the worst culprit in this regard.”

Alice has experienced the same metaphysical disappointment of material success in the Book Review that, in Portrait, Diana finds in the Style Section. Though Alice never renounces Marxism—far from it—after this point in the novel her adherence is largely relegated to a background cognitive dissonance vis-à-vis post-snobbist insight as, in true Girardian fashion, the characters turn to capital-G God. The enduring Marxist dissonance might have fallen offstage entirely had it not been so cartoonishly apparent in its real-life iteration that was the Beautiful World, Where Are You marketing campaign.

“Some recipients have noted the irony of the promotional blitz, given Ms. Rooney’s expressed Marxist values,” the article dryly states. Indeed. And yet, this very inconsistency and Rooney’s ultimate unwillingness to give up on a material panacea, even as she turns to the divine, also explains why the promotional blitz still worked. Rooney’s novel illuminates metaphysical desire without pulling back the veil entirely, without fully exposing the romantic lie. It offers penetrating psychological insights within the dominant contemporary literary ethos of political apology. In the same Times review I mentioned earlier, Brandon Taylor summarizes this ethos’s shortcomings, even as he reviews the novel favorably overall. It’s a great piece, and I agree with his analysis. If I had to graph Beautiful World Where Are You on my 2x2, I’d tack it right around the origin, around the same spot as Sense and Sensibility or Pride and Prejudice. It’s precisely the kind of brilliant, enduringly popular novel Trevor’s review of Portrait explains that mine is explicitly not.

It’s true I was after something different—something I knew would be less popular, though admittedly miscalculated just how much. Having let our politics become metaphysical, we have come to expect materialist art to compensate. And yet, hollow virtue signaling is often the result of both. I’d like to see more of the opposite. What makes a great politician—assuming for a second that this isn’t a categorical oxymoron—is actually improving the material needs of people. And, returning to Girard’s thesis: The great novelists reveal the imitative nature of desire:

In retrospect, snobbism must be identified with the first steps of genius: an infallible judgment is already at work, as well as an irresistible impetus. The snob must have been excited by a great hope and have suffered tremendous let-downs, so that the gap between the object of desire and the object of nondesire imposes itself on his consciousness, and that his consciousness may triumph over the barriers erected each time by a new desire.

After serving the author, the caricatural force of snobbism should now serve the reader. In reading we relive the spiritual experience whose form is that of the novel itself.

Surveillance capitalism is arguably rendering functional materialist politics close to impossible, but it does not actually impose the same limits on metaphysical fiction. I’m not saying that writing, let alone reading apolitical fiction is itself an act of resistance (it’s not), but rather that it simply doesn’t have to be. Great novels are worthwhile to create and consume without having any material impact at all.

This is not a very fashionable position to hold right now. I’ll leave others to connect it to the recurring MFA discourse if they want to, but debatable causes aside, I think it’s hard to argue that the prevailing literary zeitgeist isn’t pro-Marx and anti-snob. Even so, I was astonished—first while reading Luke Burgis’s Wanting and then DDN—that I, someone with a degree in literature and longstanding interest in mimesis, had never come across Girard before—had never even heard of him.

I’ve asked both Luke and Trevor about this, and it sounds like Girard’s Catholicism has been a pretty major factor in his under-appreciation. Religion is, admittedly, where Girard loses me. “All novelistic conclusions are conversions,” he argues, by way of the painful metamorphosis of (and he’s quoting Proust here) “giv[ing] up one’s dearest illusions.” When the snobbist hero, like the author before him, repudiates his mortal mediator and renounces his divinity—and thus his pride—he has, according to Girard, a necessarily Christian experience.

I don’t buy the conversion requirement. And even if I did, a Buddhist one would make more sense to me (cultivating the presence to savor the orange outside the desert, etc.). That said, not only do I think it’s a mistake to discount Girard’s work based on his religion, I think his religiosity actually increases the likelihood he’s right about literally everything else. A religious savior would blunt the pain of coming so brutally face-to-face with one’s own vanity. And being “cured” of metaphysical desire through spiritual rebirth would logically make it far more bearable to study one’s past secular illusions.

Part of me envies the believers. But honestly? I think “the cure” is just another illusion, another intellectual crutch.

At the risk of being cheesy, I’m going to stick with the crutch metaphor here for a minute. We all, as in human beings, have broken ankles, and these two illusions—I’m going to go ahead and put my stake in the ground and call them that—(1) religion and (2) the romantic lie, are like a pair of crutches we use to help us walk through life. It’s so easy to walk with both of them that we readily convince ourselves they’re legs. When you realize that one of them’s actually a crutch, though, you throw it to the side. You think you still have two working legs, when actually, you’re more reliant than ever on the other crutch. Recognizing the second crutch is excruciating. When you throw it away, the broken ankle becomes absurdly apparent. It’s tempting to reach back for a crutch. And yet, there’s something exhilarating about finally understanding why you’ve been in so much pain, even if this understanding doesn’t ameliorate it. “Beauty is truth and truth beauty,” etc. No matter how many crutches you use . . . they’re not legs.

If you have any ideas for how to walk without them, please tell me! Not that I think I’m suddenly free of illusions. If anything, I’m more acutely on the lookout for them. I’m sure my blind spot’s in the center of the mirror, as ever.

Thanks for reading my light, uplifting musings. I promise I’ll make my next newsletter about luxury bathrobes or something.

Natasha

https://natashajoukovsky.com