All the single men: Sense and Sensibility

introducing Austen Math, a 4D status model (aka my best silly idea ever)

Greetings Austenites—

I write to share the first installment of my latest literary side project, which, like many great endeavors, began as a joke that I am now taking seriously:

Eventually this will be a seven-part series, one for each of Austen’s major novels plus a cumulative report. As to the timeline and cadence though, I won’t even hazard a guess. (I’m fast approaching a particularly capricious and stressful authorial period known—rather menacingly, tbh—as submission, to which diversion is essential but my pace will inevitably submit!)

Regardless, however and whenever you find it, may Austen Math bring you all the utterly giddy delight it’s giving me.

Austen Math 101

Jane Austen, arguably the greatest novelist of all time, was the author of six marriage-plot comedies of manners published between 1811 and 1817: Sense and Sensibility, Pride and Prejudice, Emma, Mansfield Park, Northanger Abbey, and Persuasion. There is rampant dispute as to how to read them. “The people who read Austen for the romance and the people who read Austen for the sociology are both reading her correctly,” Louis Menand argues, “because Austen understands courtship as an attempt to achieve the maximum point of intersection between love and money.”

Menand’s vaguely mathematical binary is directionally accurate but insufficiently sophisticated. Austen is absolutely a marital maximizationist, but her calculations have far greater dimensional depth. As such, neither the die-hard romantics nor sociologists are reading her correctly; they are equally mistaken. Over- or under-weighting any single dimension of Austenian courtship maximization amounts to a fundamental misunderstanding of what she most cunningly gets:

Austen understood status—ahem, station; that its shoring up is hardly superficial. The intrigue of the marriage plot springs not just from uncertain affection—“will they fuck”—but the balance of such possibilities with a complex and often competing set of considerations. Status questions, basically, though to the standard socioeconomic strains I would add, particularly in Austen’s case, that of moral status. Alas, fuckability is a kind of status, too.

The Austen Math model more or less directly follows my original offhand vision, ranking all of Austen’s single men across four weighted dimensions—fortune, morals, manners, and fuckability—to develop secondary insights, calculate their individual total status, and analyze their relative marital desirability. The heroines, in turn, are judged by their dimensional weighting (and to what extent it shifts over time) versus the Austenian baseline. In other words: they are judged on the soundness of their judgment. The better a heroine is at Austen Math herself, the more virtuous she is deemed.

And what of love per se? Even the most sophisticated mathematical models are simplified phenomenological representations. Indeed, this is the purpose of models. I’d argue love is largely represented indirectly by a proprietary mix of the various dimensions—but I do not claim to capture all of Austen’s complexity, let alone any universal truths.

Methodology*

I. Dimensional raw scoring of single men

Each single man is evaluated on each of the four primary status dimensions of FORTUNE, MORALS, MANNERS, and FUCKABILITY using a whole-number score of 1 to 6, one being low and six high, based on textual analysis by yours truly.

The six-point scale both allows for sufficient differentiation across Austen’s six novels and forces non-neutrality.

II. Austenian primary status weighting (baseline)

The four primary dimensions predict total status via uneven weight distribution, in alignment with the hierarchy of Austen’s values as I have long understood them:

MORALS - 40%

FORTUNE - 30%

MANNERS - 20%

FUCKABILITY - 10%

for a total of 100%.

The formula to calculate total estimated Austenian status is a basic SUMPRODUCT: D1*W1 + D2*W2 + D3*W3 + D4*W4, where D=dimensional raw score and W=Austenian weight.

III. Secondary dimension calculations

Each pair of congruous primary dimensions yields insights into a secondary dimension. At the intersection

of FORTUNE and MORALS is WORTH,

of MORALS and MANNERS is CHARACTER,

of MANNERS and FUCKABILITY is AFFECT,

and of FUCKABILITY and FORTUNE is ELIGIBILITY.

Secondary dimension calculations may be performed either via weighted or unweighted averages of their raw inputs to harness insights inclusive or exclusive of Austenian status bias, respectively.

Note the secondary dimensions get closer to viscerally lovable personal attributes—character, affect—but would be harder to directly quantify themselves (e.g.: worth is more subjective than fortune).

IV. Heroine dimensional weight variance

Each heroine is evaluated on the difference between her hierarchy of the four primary status dimensions (again per my textual analysis) and Austen’s. Like in the Austenian baseline, the heroine’s top-priority dimension is weighted 0.4, with -0.1 for each subsequent priority.

The formula for dimensional weight variance is: |W1-H1|+|W2-H2|+|W3-H3|+|W4-H4|, where W=Austenian baseline weight and H=heroine weight. I use this absolute-value “spread” calc over true squared variance for its simplicity, clarity, and sufficiency given the small size of the data set. The score will fall between 0 and 0.8 in increments of 0.2, and can be roughly interpreted as follows with regards to the heroine’s judgment:

0 - Unimpeachable

0.2 - Sound

0.4 - So-so

0.6 - Precarious

0.8 - Misguided

I.e., the lower the score, the better her judgment. In some cases, heroines’ dimensional values change over the course of the novel, in which cases I calculate both starting and ending hierarchy for comparison to estimate their development.

*Feel free—nay, encouraged—to quibble with any of this. We are here first and foremost to have fun, and banter is damn close to my definition of it.

Credentials

While admittedly an amateur Austen scholar, I am the daughter of a doting professional one—and a professional novelist and management consultant myself (see: Portrait, patents). My undergraduate degree is in English and my graduate an MBA: a thoroughly Austenian compromise. Her voice has been inseparable from that of my own conscience since I was ten years old.

Part 1: Sense and Sensibility

We start with Austen’s debut novel—and what a debut it is. The eldest two Dashwood sisters, Elinor (“Sense”) and Marianne (“Sensibility”), are beautiful, accomplished, and woefully under-resourced following the death of their father and passing of the familial estate to their half-brother, John. Things are looking up when John’s horrible wife’s remarkably admirable brother—Mr. Edward Ferrars—and Elinor develop some serious mutual “esteem.” Until, that is, the horrible wife/sister intervenes, driving her in-laws from their former home.

Elinor, Marianne, their mother, and younger sister resettle father afield than expected at Barton cottage, offered under attractive circumstances by their cousin Sir John Middleton. In these new environs, the family meets the dashing Mr. John Willoughby after he romantically rescues Marianne, and—less romantically—the staid and dependable Colonel Brandon, who owns the estate at Delaford, but also, alas, is positively ancient at thirty-five.

The single men

Mr. Edward Ferrars; Mr. John Willoughby; Colonel Brandon

Fortune

Colonel Brandon’s stable Delaford income of 2,000£ per year makes him easily the richest suitor in Sense and Sensibility. However, we must leave room for the far richer men of subsequent novels (the Bingleys let alone Darcys of the oeuvre), so he tops out at 4/6.

Edward and Willoughby find themselves in less advantageous financial positions due to similar uncertainties. “[T]hough Willoughby was independent,” Austen tells us, “there was no reason to believe him rich. His estate had been rated by Sir John at about six or seven hundred a year; but he lived at an expense to which that income could hardly be equal, and he had himself often complained of his poverty.” The riches he anticipates as the heir to Allenham, an estate near Barton cottage, are dependent on his reclusive relative Mrs. Smith’s favor, much as Edward’s inheritance depends on his mother’s. Edward has even less guaranteed—only 2,000£ total—but is also far less spendthrift. Both elderly women make additional funds contingent precisely on the young men marrying more—and given the specific irony of this stipulation on top of its general precarity, both men score 2/6.

Morals

Edward is so morally upright even Marianne admires him in spite of his courtly deficiencies. Colonel Brandon is similarly high-principled. Both men hold themselves accountable to past mistakes while remaining steadfast in the present (e.g., Edward to Lucy Steele, Brandon to Eliza), even when doing so runs contrary to their own desires. Easy 6/6 for both.

Willoughby is their utter opposite, morally guided by selfishness. While with regard to Marianne specifically, his confession to Elinor might tempt mercy, his prior seduction and abandonment of Eliza amounts to the height of Austenian moral outrage:

One observation may, I think, be fairly drawn from the whole of the story—that all Willoughby’s difficulties have arisen from the first offence against virtue, in his behaviour to Eliza Williams. That crime has been the origin of every lesser one, and of all his present discontents.

1/6.

Manners

The manners of all three men are more nuanced. Of Edward, Austen says “his manners required intimacy to make them pleasing. He was too diffident to do justice to himself; but when his natural shyness was overcome, his behaviour gave every indication of an open, affectionate heart.” In direct contrast: “Willoughby was a young man of good abilities, quick imagination, lively spirits, and open, affectionate manners.” And of Brandon: “His manners, though serious, were mild; and his reserve appeared rather the result of some oppression of spirits than of any natural gloominess of temper.”

So in all three cases, we see pros and cons. Edward sucks at first impressions, but later more than makes up for it; Willoughby is immensely charismatic, but too familiar; and Brandon’s solemnity belies his supreme gentlemanliness. Also in all cases: I’d say these pros outweigh the cons. All get 4/6, with differentiation manifesting rather, as we’ll see, in the secondary dimensions.

Fuckability

Let’s start with the easy one: Willoughby. Austen says “his person, which was uncommonly handsome, received additional charms from his voice and expression.” This is Austen-speak for very, very hot. Like, Jude Law in The Talented Mr. Ripley hot. 6/6.

Edward and Colonel Brandon’s scores are less straightforward. Of the former, Austen says in no uncertain terms “He was not handsome”—but Elinor, maybe the most Austenian of all her characters—later maintains:

At first sight, his address is certainly not striking; and his person can hardly be called handsome, till the expression of his eyes, which are uncommonly good, and the general sweetness of his countenance, is perceived. At present, I know him so well, that I think him really handsome; or at least, almost so.

Edward also has youth on his side, in heavy contrast to the Colonel: “His appearance however was not unpleasing, in spite of his being in the opinion of Marianne and Margaret an absolute old bachelor, for he was on the wrong side of five and thirty; but though his face was not handsome, his countenance was sensible.”

So, while neither are good-looking, Edward seems to have the clear edge over Brandon in fuckability, being arguably “almost so,” a decade younger, and of generally sweet over “sensible” countenance. Let’s say 4/6 for Edward and 2/6 for Brandon. (I cannot guarantee that Hugh Grant and Alan Rickman have no influence here.)

Secondary dimensions & insights

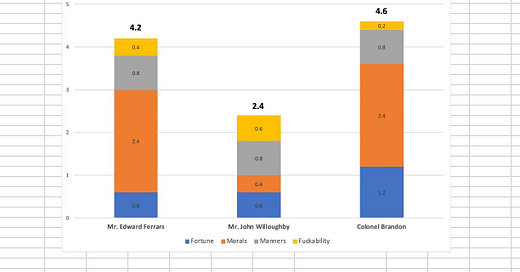

Graphing the raw scores above along with their calculated unweighted secondary dimensions, we see the following:

Absent any weighting, the three single mens’ differences are distinguished more by dimensional mix than total area; more by the nature of their strengths and weaknesses than their total dimension-agnostic appeal. This is especially true when you consider that the extremity of Willoughby’s moral impoverishment is pretty late-breaking. Along exterior lines, he’s the easy favorite—not just in terms of sheer fuckability, but in affect and eligibility. Austen follows the sentence about Willoughby’s “open, affectionate manners” with:

He was exactly formed to engage Marianne’s heart, for with all this, he joined not only a captivating person, but a natural ardour of mind which was now roused and increased by the example of her own, and which recommended him to her affection beyond every thing else.

Likewise, that Willoughby eventually weds Miss Grey and her fifty-thousand pounds speaks to his outsized eligibility.

Edward and Brandon conversely gain the bulk of their appeal from more interior dimensions. On top of their sterling moral characters, Brandon’s edge in worth balances Edward’s in affect to, all things considered, cut similarly attractive matches in line with the senses and sensibilities of our heroines.

Weighted Austenian Total Status Model

Here’s where Willoughby gets smacked:

Austen’s values are in inverse relation to Willoughby’s strengths—hence why, for all his attractive qualities, it’d be hard to think Marianne anything but fortunate to have escaped him. Indeed, she eventually accepts this herself:

“At present,” continued Elinor, “he regrets what he has done. And why does he regret it?—Because he finds it has not answered towards himself. It has not made him happy. His circumstances are now unembarrassed—he suffers from no evil of that kind; and he thinks only that he has married a woman of a less amiable temper than yourself. But does it follow that had he married you, he would have been happy?—The inconveniences would have been different. He would then have suffered under the pecuniary distresses which, because they are removed, he now reckons as nothing. He would have had a wife of whose temper he could make no complaint, but he would have been always necessitous—always poor; and probably would soon have learned to rank the innumerable comforts of a clear estate and good income as of far more importance, even to domestic happiness, than the mere temper of a wife.”

“I have not a doubt of it,” said Marianne; “and I have nothing to regret—nothing but my own folly.”

Marianne finds a far better match in Colonel Brandon—per Austen Math, the novel’s highest-status man. Edward scores only a bit lower, and thanks to Brandon’s generous offer of the modest clergy living at Delaford, probably becomes an even better match for Elinor than his Weighted Total Status would suggest. While, as we shall see, Elinor understands the high priority of “something to live upon,” her prudent nature and modest wants, aligned with Edward’s, significantly reduce the barrier to “enough.” Colonel Brandon is far richer than Edward—but “enough” for Marianne is also more.

Factoring in this nuance, Edward and Brandon’s status scores effectively become a wash, with each suited best to his own bride.

The heroines

Miss Dashwood (Elinor); Miss Marianne (Dashwood)

Basically every time we discuss this novel, my father reminds me “Elinor is the heroine who is right and Marianne is the heroine who is wrong.” Elinor mirrors Austen’s dimensional prioritization in every way for a judgment high-score of 0 - Unimpeachable.

I imagine early-novel Marianne objecting stridently to my weighting methodology itself and the very concept of prioritization—“oh, but everything is important, Natasha! How can you bear these cold calculations.” But of course this is partly why she is wrong. Marianne’s chief error in judgment is not undervaluing morality so much as mistaking manners and taste for it. Onto Willoughby’s “open, affectionate manners” she projects Edward’s “open, affectionate heart.”

As such, from the beginning of the novel (and in spite of her imaginary objections), Marianne’s error reveals her dimensional priorities to be

1. MANNERS

2. FORTUNE

3. FUCKABILITY

4. MORALS

for a judgment delta vs. Austen of 0.6 - Precarious. By the end, Marianne sees morals for what they truly are, and by catapulting them to her top priority, closes the gap to 0.2 - Sound. She’s still not on Elinor’s level, but becomes fully worthy of Brandon’s affections and a suitable partner to him in the mutual cultivation of domestic felicity.

Other misc. notes from this read:

Damn, hits different from “the wrong side of five-and-thirty”!

I know people in the nineteenth century were obsessed with hair, and I still manage to be perennially surprised just how obsessed they are with hair.

She’s even franker about money than I remembered, too.

The Palmers are perfect flat characters. Forster could have used Mr. Palmer as effectively as he does Lady Bertram in Aspects of the Novel.

Austen’s skewering of Lady Middleton’s obsession with her children has well nigh prophetic contemporary relatability, and is way funnier to me as a mother than it was as a child.

I need to re-watch the 1990s movie with Emma Thompson and Kate Winslet, which is incidentally the only film adaptation of any Austen novel I endorse.

NEXT UP (maybe after an end-of-year reading letter? Who knows exactly when)…PRIDE AND PREJUDICE. You probably read it in high school. Many think it her best. But how do the single men stack up?

We shall see—

ANJ

I admire your commitment, your originality, your math skills, and your devotion to Austen. This is brilliant. But the answer you are seeking is Darcy. The perfect man brought to life by a woman who never knew one. In other words the perfect man is imaginary.

This is brilliant.