I. Introductory

Thorstein Veblen is the sort of historical figure whose ideas you’re probably familiar with even if you’ve never heard of him. We’re talking about the guy who coined the terms “pecuniary emulation” and “vicarious leisure” and most famously “conspicuous consumption.” His seminal work The Theory of the Leisure Class is as close a forerunner to Deceit, Desire & the Novel as I think there is; René Girard invokes Veblen by name. And in the introduction to my edition (Oxford World Classics), Martha Banta duly writes: “[m]ore often than not it was the novelists of Veblen’s day who cut to the core of the book’s insights.”

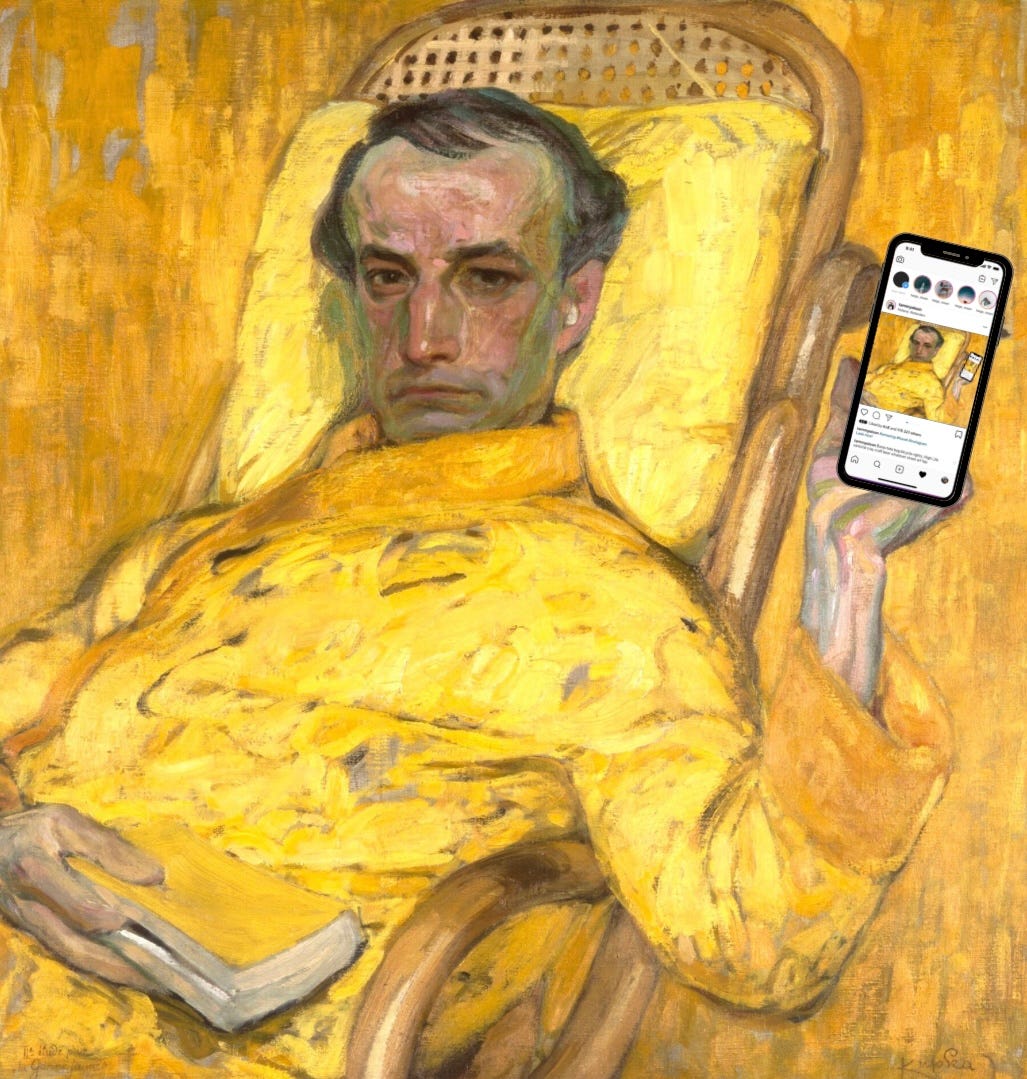

The Theory of the Leisure Class is shockingly, almost disturbingly relevant today, and I’m struck by this whenever I return to it. Still, even setting aside the cringy racial stuff, Veblen’s history of the evolving sophistication of aristocratic class signals inevitably falls short in one respect: it was published in 1899, and, to use his own nomenclature, we entered a new “phase of culture” about a century later. We may be on the precipice of yet another, but for now let’s just call it all the internet phase. David Foster Wallace predicted a few of its mechanics with decidedly Veblenite flair in what I’d argue is the finest passage of Infinite Jest—but I’ve been thinking for a while that there is still, in 2023, a sizable gap to fill, and I might as well be the one to fill it.

The internet is a big place with myriad venues and mechanisms for showcasing elite consumption and leisure—“honorific waste”—but I think it should be fairly obvious why I’ve chosen to focus on Instagram. Of the major social platforms, it is the most mature that is both image-led and persona-centric. (For comparison, I would categorize Pinterest as image-led but not persona-centric, Twitter as persona-centric but not image-led, and TikTok as both image-led and persona-centric, but less mature.) Many of the Veblenite phenomena I’ll describe are relevant to other platforms too, of course—but tracing the evolution of one seemed the most salient way to present them.

II. Phases in Phases

The driving mathematical force underlying the internet phase of culture is recursion. Its inherent propensity to accelerate iteration has reduced what I want to call social cycle time. As I’ve put it in the past, “the shifts in taste that once evolved over a generation now cycle in and out of vogue at a dizzying pace online”—and so we cling even more tightly to cues from our models and things like The Cut’s nail-biting guide to post-pandemiquette without entirely trusting them. Manners are costly class-signifiers in any phase of culture, but the internet phase specifically is defined by its further embedded cyclical phases and “the Catch-22 of modern etiquette: that if subverted en masse, what was once a gaffe becomes the norm, and the outmoded norm a gaffe.”1

Algorithmic feeds like Instagram unleashed in 2016 recursively accelerate recursive acceleration. The nested convolution of the previous sentence is a feature, not a bug.

III. Digital Mirroring & Invidious Immediacy

In the early days of Instagram—call it 2010-2012, pre-Facebook acquisition—the application largely just reflected established offline signifiers of consumption and leisure in Veblenite “pecuniary culture.” Users mainly followed real-life friends and acquaintances, with digital “invidious comparison” tied to the accounts of one’s incrementally aspirational models in real life.

Instagram’s initial advantage vs. offline pecuniary signaling and especially conspicuous leisure was, true to its name, sheer visual immediacy. It made conspicuous leisure more conspicuous. Instead of envying my friend’s trip to Turks & Caicos only in theory until she came back with a glowing tan, I envied her while it was happening, a direct witness to the sand and sun and finely-honed bikini bod suggestive of more routine sportif leisure. In other words, early Instagram was primarily a channel innovation for real-world pecuniary emulation; it offered a better, faster way to communicate existent enviable data about your physical self.

Instagram aesthetics and behavioral norms in these early days reflected posts’ utility as digital receipts, offering social proof of real-world leisure and consumption. Exotic locales, exclusive company, costly yet disposable wardrobes, and flattering portraits (though not gratuitous selfies) were all highly valued, but unless you were independently interested in photography, production quality was less important. Filters were obvious and assorted, overlaying pictures users would have been almost as happy to share without them, as they had and perhaps continued to do on Facebook. There was little thought given to post cadence, with users unselfconsciously sharing the highlights of their real lives in real time—perhaps several posts in a day if the occasion merited it. Frequency was desirable only to the extent it demonstrated abundant documentable experience rising to the level of enviability, with status and glamour accruing more or less in proportion to offline social capital and illustration of leisure-class “canons of taste.”

Note this sub-phase, in reflecting and sharing genuinely enjoyable real-world experience, could often be quite fun. It could be misery-making too—but this variability is also true of offline life.

IV. Egoic Bifurcation & Curatorial Anxiety

Instagram’s rapidly growing user base and features like the “Explore” tab in 2012 progressively expanded the pool of models for invidious comparison and pecuniary emulation. Alongside the normalization and entrenchment of quantitative, gamified measures of social approval—follows, likes—this created a heightened sense of social competition that both augmented individual pressure to differentiate and planted the seeds of what I’ll call egoic bifurcation—the sense of having distinct digital and physical selves, both of which are still “you.”

Property was thus appalled

That the self was not the same;

Single nature's double name

Neither two nor one was called.

—William Shakespeare, “The Phoenix and the Turtle”

Egoic bifurcation changed what social differentiation entailed, offering a digital path to high status via its own currency (follows, likes) that was increasingly disconnected from offline pecuniary repute. The timeline here aligns precisely with Jonathan Haidt and Co.’s quantifiable data on the teen mental illness epidemic—and also just makes intuitive sense, as the separation of digital projection from source material also underpinned the rise of the selfie. Egoic association with our discrete, frozen, inorganic “selves” is why selfies seem, as I’ve argued before, to solve two of humanity’s deepest issues: lack of control, and the problem of immortality.

Instagram thus became a place not only to gain status, but to preserve it. There was now a delicate balance to be struck between the salience of individual posts and curatorial grid consistency in the expression of one’s “personal brand.” The ensuing arms race in production quality, aided by ever-improving iPhone cameras and secondary apps like VSCO, manifested in self-conscious self-imposed branded differentiation tactics that themselves became ubiquitous. You’ll surely recall some of these design trends—heavy white borders, vibey filter presets—as well as consistent iconographic motifs like letterboards; they became digital artifacts of honorific waste for Instagram’s leisure class, i.e., influencers, copied by smaller and smaller accounts.

The time and forethought required to showcase all this digital honorific waste led to lag times between image capture and Instagram post—the “#latergram.” Posting cadence became a fraught strategic endeavor, with influencers modeling evolving mores, like not sharing more than one post per day. Showcasing invidious immediacy more broadly seemed desperate and passé. In combination with the grid’s promise of curatorial preservation, the uncertainty surrounding rapidly shifting etiquette and quantifiable social penalties for its transgression transformed posting into an increasingly high-pressure preoccupation. One’s self-mythology was ever at stake.

I intentionally set The Portrait of a Mirror at the end of this sub-phase in 2015, a moment in history I’ve likened to the Narcissan one Caravaggio chose to capture in the painting that graces the novel’s cover. It’s the height of self-obsession just before a death spiral.

V. Illusory Perfection & Professional Leisure

Around the same time Instagram introduced the algorithmic feed, influencers began to cross egoic bifurcation’s critical inflection point: the abject subjugation of the physical to the digital self. Likes and follows, once the validation of offline status, became its leading indicator. Great physical inconvenience if not outright labor was tolerated in order to create the illusion of its absence—the illusion of leisure. The illusion of perfection.

Similar to the way the publication of a fake news story becomes a reportable fact, these illusions increasingly had the potential to yield actual pecuniary rewards, promptly reinvested in optimizing further digital honorific waste to project ever greater enviability. The value of illusory leisure to create reality is what the HBO documentary Fake Famous would later explicitly hack.

The ultimate success of such endeavors would seem to be, and probably hypothetically was, emancipating the physical self to indulge in real leisure—but the very concept of “real leisure” had, by this point, become muddied with its projection and the extreme reprioritization of “good future memories” over experience—even if these “memories” were highly manipulated or outright fake. So no matter how successful an influencer became, there was never any true respite. The prize for winning the pie-eating contest was always more pie.

As the quest for illusory perfection reached its apex, anxiety skyrocketed over whether one’s posts passed memorial muster to the point of driving users to Snapchat’s relatively liberating ephemerality—and the copycat introduction of Instagram “Stories” in late 2016. Within Instagram’s preexisting social infrastructure though, the impact of Stories on perfectionism was akin to how building a new highway in New York or Los Angeles only creates more traffic. Both Stories and video in general made it harder to fake conspicuous leisure, while the proliferation of editing apps reduced the digital honorific waste associated with sheer branding aesthetics, and thus their value.

In concert with, above all, the algorithm, these changes were much to the advantage of already successful influencers, now hiring teams of people to create little media empires of pristine editorial content. The average user could scarcely hope to keep up. As is so often the case in recursive regimes, Instagram’s rich got richer—though the winning projection of digital leisure now not only required labor: it became a literal job.

There is at minimum a strong correlation, if not a causal link, between the rise of professionalization and the decline of fun. This is especially true of snobbist industries, which I’d argue influencing is; the self is the ultimate mission-driven organization. Allie Rowbottom’s novel Aesthetica explores the bleak dopaminergic gamesmanship of full self-professionalization at the height of this sub-phase, as well as its fast-following phenomenon: the reverse-engineering of digital filters onto the physical self through preservative cosmetic procedures—the birth of “Instagram Face.”

VI. Breakdown & Manufactured Nonchalance

By 2017ish, illusory perfection started to crack. You’ll remember the emergence of a predictable cycle: such-and-such major influencer posts an exposé of their misery, admitting their seemingly perfect life is anything but. These confessions generally arrived in a long, intimate caption below an unfiltered selfie with no or minimal make-up, the photo making her (it was almost always a “her,” which is also reflected in Haidt’s research) look comparatively human—yet still often prototypically beautiful and well-lit. Sometimes there was a side-by-side with a filtered version, drawing attention to the extremity of photoshop and filters. A gossip site or even a legitimate news outlet might pick up the story of so-and-so’s “brave” revelation and the praise would roll in, with any outlying trolls serving to reinforce the bravery narrative.

Much of what Instagram breakdowns revealed about illusory perfection was true, and I don’t doubt many of them were genuine attempts to repair egoic bifurcation. But the attention and clout influencers received in their reversals ironically also served to accelerate the pursuit of Instagram Face offline; nostalgia for the digital mirror morphed into a sophisticated strategic pivot. Being “real” or—tellingly—“natural” online was not a true return to nature, but something more akin to Marie Antoinette’s Anglo-Chinese gardens at the Petit Trianon contra the extreme artifice of those surrounding the Chateau Versailles. “It’s the natural evolution of ostentation: the display of wealth precisely by concealing it. Hers is the more modern mode of luxury, a second-order and more sophisticated form of control.” Or as Oscar Wilde put it: “Being natural is simply a pose, and the most irritating pose I know.”

Even in cases where the initial breakdown image was truly, refreshingly unflattering, this was often a one-off en route to “unfiltered” near-perfection—digital sprezzatura—the internet phase equivalent to the very old idea I like to call manufactured nonchalance. Its favor here offered another systemic advantage to Instagram’s leisure class: unfiltered near-perfection was more difficult and costly to achieve than filtered perfection. Photoshop was replaced by SoulCycle and personal trainers and now Ozempic, filters first by fillers, later dissolved for more “natural” deep-plane facelifts.

Altered faces and bodies in turn benefit from ever more sophisticated filters (have you seen Bold Glamour on TikTok?), sending people back to the doctor for snatched jawlines and buccal fat removal, and—and—and. People (and reflections) look more alike with every oscillating iteration. Homogeneity only heightens the import of subtle variation, raising the pressure and stakes of differentiation—and Veblen starts running into Girard.

VII. Satire & Conspicuous Crap

Two of the boldest strategies that emerged to escape Instagram’s mimetic crisis involve humor and a special, anti-flavor of digital conspicuous waste I’m going to call conspicuous crap. The former is perhaps best illustrated by the Australian comedian Celeste Barber, who rose to fame mercilessly parodying influencer and editorial content with her recognizably human body in average production quality. It’s hilarious—I love Celeste Barber—and there’s a kind of public service in what she’s doing, but it’s also important to note she’s leveraged it into full-on celebrity clout. Her popularity on Instagram has catapulted her onto the cover of the very editorial magazine covers she’s satirizes. She’s become so entrenched in the elite that celebrities ask her to parody them to bolster their own status.

Conspicuous crap is more convoluted still, and again best illustrated by an example. Consider Timothée Chalamet’s post of . . . a Cup of Noodles and his foot:

De gustibus non est diputandum, but I think this is as close as an image gets to being objectively uninteresting. The subtext here is I can post the most banal crap on the planet and it will still get three-million likes. It signals stratospheric status yet max nonchalance, reinforcing stratospheric status.

I’ve been developing a hypothesis that conspicuous crap is specifically a sign one has crossed the magic, almost Midas-like status threshold whereby the power of their content is derived entirely from the who as opposed to the what. This idea is related to Ernst Kris and Otto Kurz’s ingenious book Legend, Myth, and Magic in the Image of the Artist, and I may have to write more about it in the future. In the meantime, I’ll just note that, counterintuitive as it may seem, conspicuous crap posts are still personal branding, and powerful branding at that. Ultimately, both of these approaches to differentiation benefit successful individuals but still reinforce the recursive digital pecuniary system.

VIII. Hypercuration, Outsourcing & Withdrawal

Another set of anti-mimetic strategies seem to more explicitly acknowledge the pie-eating dynamics—that the only true way to win on Instagram is not to play. To those who have successfully withdrawn and actually deleted your accounts: I salute you. But I worry the “I give up” impulse more often manifests in projecting the mere appearance of withdrawal through hypercuration—posting with extreme infrequency—and social media outsourcing, which is exactly what it sounds like.

I’m not at all convinced that hypercuration actually leads to less time spent in-app; it gained popularity with the pandemic, when people by and large had fewer things to post about yet spent more time than ever online. I get the sense it’s rather more a defensive posture, designed to maximize informational asymmetry—the benefit of seeing without being seen. Meanwhile, the message it sends is one of nonchalance and being above engagement—that one is simply too busy and enthralled by one’s life offline to care about something so “superficial” as Instagram.

Outsourcing one’s social media presence accomplishes something similar. Think of celebrities who conspicuously hire people to run their accounts for them, revealed in glossy profiles alongside their progressive values and statements like “transcendental meditation changed my life.” A more quotidian example would be couples where only one of the partners posts regularly—spoiler alert, it’s usually the wife. You often see this and hypercuration deployed in concert. Receipts of the offline partner’s leisure exist for invidious comparison alongside the engaged one, but with the direct implication of having performed little (in resharing) or none of the digital work. Veblenite pecuniary dynamics strike again.

IX. GPT-4 & Beyond

In case you missed it, GPT-4 launched yesterday:

I am wary when people announce the death of things, and this is no exception—but the thread above is nonetheless remarkable, and it seems very possible to me that the recent advances in AI may soon mark not just a new sub-phase, but an entirely new phase of culture. Are we in the AI phase already? Will GPT-5 initiate it? GPT-50? Who knows. I don’t think the inability to distinguish between real and fake would in and of itself kill Instagram, though; we already struggle with this today. The question, rather, will be whether or not Instagram continues to be an effective mechanism for signaling social status in one way or another—however the specific Veblenite markers of manners and etiquette, homogeneity and differentiation, consumption and leisure and new, unknown tokens of honorific waste might evolve.

Incidentally, my original opening to the Electric Lit piece, which was cut by editorial for Veblen’s obscurity, was:

“There are few things that so touch us with instinctive revulsion as a breach of decorum,” wrote Thorstein Veblen in his alarmingly poetic 1899 socioeconomic study, The Theory of the Leisure Class. “A breach of faith may be condoned, but a breach of decorum can not. ‘Manners maketh man.’”

I am so fascinated by this, especially as I consider my own social media activity/consumption/"presence" and what i actually want to be doing on the internet.

Your explanation of "manufactured nonchalance" remind me of things written by Jess DeFino (https://jessicadefino.substack.com) and others about how skincare has been usurping makeup, how trends are increasingly leaning toward "clean girl" and "no makeup makeup," and how it seems like "undetectable" plastic surgery could usurp skincare. That's similarly wrapped up in class & class performance. This essay also reminded me of this video on Alexa Demie "the power of privacy and mystique": https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=YvYoQLcFlHw

Thanks for writing!

Marvelous. Never has useless been so relevant, not to say useful.