[NOTE: this essay is about Master of Fine Arts degrees not Multi-Factor Authentication. Apologies to the readers I’ve confused! You’re right—I know better.]

MFA essays: there are so many of them. I’m not being cute with the title here—I promise this is not another one. Aside from what would be pure autobiographical vanity, I have little to say about MFAs that hasn’t been said already either by colossi of the subgenre—Chad Harbach, Elif Batuman—or in more recent newsletters by Vera Kurian, Erik Hoel, and Lincoln Michel. Some of these writers have MFAs and some do not, and their takes do occasionally contradict and even directly refute one another’s, but collectively they basically cover what I would consider the range of reasonable positions and considerations with regard to this particular course of graduate study. My subject today focuses rather on the absurdly heated discourse that invariably spins up online in reaction to the topic, a predictable cycle of outrage over the same series of arguments even as we lament, with excruciating self-awareness: oh my god we’re doing it again. Call this a meta-MFA essay instead.

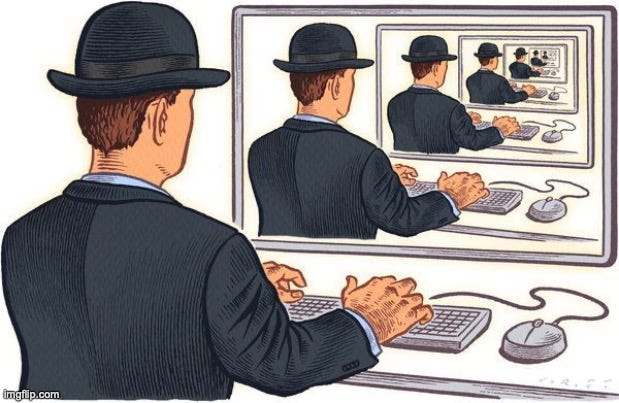

To address the obvious here first: the outrage machine itself is recursive, and it takes precious little to set off a five-alarm fire on literary Twitter. Other recent “controversial” topics include riveting forays into word counts and whether or not it is important for writers to read. I am not exaggerating! But I also don’t want to belabor this point, because there is something observably more enduring about The MFA Discourse specifically (I’ll come back to C. Thi Nguyen’s brilliant paper on Twitter later). Its intensity ebbs and flows, but the tension never seems to totally dissipate. At times, it gets ludicrously vicious. In the aftermath of Erik Hoel’s essay, for instance, pro-MFA tweets escalated from the realm of “I disagree with this” to ad-hominem attacks by people (and I almost want to use the word “users” here) who, by their own admission, had not read the piece at a frankly alarming rate.

Why?

Hypothesis #1: egoic regret avoidance

Our egos are shrewd defense attorneys, engineered to represent us well in the court of law that is our own minds.

Regret is painful, and our egos are particularly hawkish in helping us avoid it. This is an idea I explored at length in The Portrait of a Mirror, even in connection with MFAs specifically:

Turning down those modest-yet-prestigious MFA stipends for commonplace big money at Portmanteau was a decision that Dale had, over the years, spent a great deal of time reminding himself how much he did not regret. His initial plan had been to defer acceptance for one year—just long enough to cement his relationship with Vivien and earn the Portmanteau signing bonus—but then he got promoted early and was slated to make even more money and didn’t it perhaps make more sense to defer again? He deferred again. A few weeks later, the economy collapsed. Pandemic uncertainty swept across the upwardly mobile young-professional landscape, and it started to look like he had dodged a real professional bullet. The next summer his friends with newly minted MFAs—even top ones—were by and large forced to accept teaching positions at third-rate institutions or even low-paying noncreative jobs to support their writing on the side. When Dale met up with them, the most innocuous conversations often exposed the sharp divergence of their material circumstances. His friends were envious and embarrassed by their envy, which embarrassed Dale, too—even as it pleased him, and made his friends ashamed of embarrassing him, and Dale ashamed of his perverse pleasure. It was all so obvious, and yet sedulously unsaid. American liberal politeness required the forceful denunciation of inequalities in the abstract while pretending not to notice them between friends. How could Dale say no when Portmanteau offered to pay for his MBA? He couldn’t.

And yet: having taken the MBA path myself (though unlike Dale, I never considered an MFA; my “road not traveled” was a PhD), I know enough about the analogous question in the business sphere to sharply undermine, if not refute the egoic regret avoidance hypothesis as the source of ire.

If MFA outrage was merely the byproduct of regret avoidance, wouldn’t MBAs—and JDs, MDs, Engineering PhDs, &c.—defend their degrees (or lack thereof) with similar vehemence? But this is not anywhere close to the case. Certainly there is anxiety surrounding applications, and disappointment for those who do not get into their choice school at the time, but the idea of vituperative debate between MBAs and non-MBAs years later online is basically inconceivable to me. I can picture it even less in the case of JDs—who, for the record, love to argue and be right about things—but are nonetheless forever admonishing other people “do not go to law school!”

Hypothesis #2: snobbism

My friend Blake, who is a writer and JD, posited the following in response to my professional school analogy:

This seems plausible, and got me thinking that The MFA Discourse tends to conflate two largely discrete questions:

MFA vs. non-literary credentialization for a non-literary career, which is at the heart of Dale’s anxiety in Portrait, as well as Vera Kurian’s essay, and I will refer to as the material debate

MFA vs. other squarely literary options, as framed by Harbach in “MFA vs. NYC” and Batuman as MFA vs. PhD, which I will refer to as the metaphysical debate

There are material considerations to the metaphysical debate and vice-versa, and career and credentialization are central to both, but the material debate is more a question of what you do to make (vastly different amounts of) money, the metaphysical more a question of how you are (usually poorly) compensated for your literary art specifically.

I say MFA “vs.” non-literary credentialization in the first question, but I actually suspect that, to Blake’s point above, a great deal of handwringing on both sides of the material debate lays not in these degrees’ divergence but uncomfortable similarity. Either the MFA is a professional credential, which seems to put its graduates on the same moral plane as those who “sold out” and got more lucrative ones—or it is not, and graduates can claim rights to artistic sanctity but not economic returns. While my hunch is that most MFA programs deliberately evade giving a firm answer here, I’d posit the MFA is a professional credential, and the specific credential it provides is the qualification to teach in MFA programs. If this sounds like a “pyramid scheme,” as the anti-MFA contingent often contends, it’s no more of one than the MBA complex is.1 The difference between them rather lies in labor supply and demand outside the academy. Yes, there are a handful of big, big winners in the margins of both—set them aside; they are outliers. Your average MBA has more viable non-academic career options with better material benefits than your average MFA does. And because a key objective of getting an MBA is explicitly a career in business with the expectation of making money, prestige in this sphere tends to follow these material benefits. The relative reputation between companies in high-percentage MBA-track industries (management consulting, investment banking, tech) is highly correlated to pay and other extrinsic considerations. (Channeling Nguyen: dollars are the “points.”)

While material success sometimes tracks with cachet in literary pursuits too, such instances tend to fall more on the “New York” side of the metaphysical debate in relation to publishing advances for novels, which on the whole pay better than the MFA’s favored form: short story collections. But again, when we remove the blockbuster outliers and secondary film/tv opportunities, authors are generally not making much—rarely a living wage on book sales alone. They need to do something else too, and few “something elses” in the literary world offer enviable wages vs. equivalent positions in nearly any other industry. Metaphysical desire steps into the material vacuum, and snobbism reigns. The Iowa Writers’ Workshop is arguably less like Harvard Business School than it is Proust’s Faubourg Saint-Germain. Its power is derived not from material or artistic benefit, but the very essence of snobbism: nothing. This is not to single out Iowa, which I’m using metonymically here, nor is “nothing” a value judgment of MFAs in particular, but simply definitional when it comes to snobbism.

If an MFA degree’s worth rests above all in the perception of its worth itself, it follows that defending its perception would be of critical importance to many MFA graduates. This is a compelling point for the snobbism hypothesis, and likewise explains non-MFAs reciprocal frustration. Status and value judgments based on snobbism are understandably frustrating to excluded parties. Nowhere is this more true than for other snobs—and New York is full of them. Notably: publishing is a snobbist industry too.

The general characteristics I’ve observed in snobbist institutions/industries include (and I’m admittedly also drawing from my time in major museums here):

Mission-driven

Low demand for labor + high supply of labor

A few high-prestige sinecures at upper-levels with ultra-low turnover

Low wages, underemployment, boredom, and burnout through the rest of the workforce

Limited opportunity for advancement (“someone has to die,” etc.)

Antiquated infrastructure, systems, and technology + many repetitive, low-value tasks

Appeals to mission/ prestige/ intrinsic motivation to compensate for material/ extrinsic lack2

Erin Somers’s smart piece on recent editorial resignations mentions at least half of these things. Perhaps Isle McElroy put it best:

All this said, while I think snobbism nicely elucidates mechanics of desire that logically underly both the material and the metaphysical debate, I’m not sure it fully accounts for the vitriol, what with snobbism’s most powerful tool being feigned indifference. Before all-out crowning hypothesis #2, there’s a third that still deserves our consideration.

Hypothesis #3: partisan polarization

Has The MFA Discourse devolved in a similar manner to what we’ve seen in the political arena? Let me clearly state that I am not implying one side or the other is akin to Democrats or Republicans specifically. My question is rather whether the same forces that have transformed ideological political divides into tribal cults in recent years have also turned up the temperature between pro- and anti-MFA factions. Here we arrive at C. Thi Nguyen’s fascinating work on Twitter gamification and echo chambers. In the former paper, he summarizes the latter as follows:

. . . echo chambers are best understood as structures of manipulated trust. Echo chamber members have been systematically taught to distrust everybody on the outside (Nguyen, 2018). To put it more formally: an echo chamber is a social structure in which:

1. One must subscribe to a certain belief system to be a member.

2. That belief system includes the belief that all non-members are untrustworthy, and all members trustworthy.

Nguyen distinguishes echo chambers from epistemic bubbles, which rely on the sheer absence of contrary opinions as opposed to their systematic discrediting and are thus more easily popped. By contrast, the properties of echo chambers allow for participants to be well-informed and rationally minded, and yet still susceptible to their effects.

Order of exposure matters in manipulated trust, and you can already see some of the mechanics Nguyen outlines forming in Harbach’s “MFA vs. NYC.” A young writer enters one or the other environment, and the respective systems serve to inculcate their respective literary beliefs within their respective social structures.3 Note Harbach’s essay, which was published in 2010, does not contain the words “Twitter,” “internet,” or “online”; social media and the broader surveillance economy apparatus act not as instigators but accelerants to polarization. Twitter’s reductive gamification increasingly rewards the most extreme tweets when a new MFA essay drops, and literary users are particularly hungry for its easily digestible “points” coming from snobbist landscapes of baffling nuance. Followers in users’ factions have ever greater confidence to like and retweet without the pesky bother of reading the piece for themselves, and the recursive outrage machine takes over.

I find Nguyen’s whole line of thinking salient, and will put my stake in the ground here: a combination of hypotheses #2 and #3 explains the lion share of why The MFA Discourse has become such an outsized beast. Tribal prestige is precisely, quantifiably at stake with its every iteration.

Thanks for reading,

Natasha

https://natashajoukovsky.com

Or most PhDs, for that matter. JDs and MDs are notably different, in their formal and regulated professional barriers to industry practice outside academic credentialization.

Ironically, material precarity can even be a source of literary prestige, the opportunity cost functioning much like a Veblen good, and glamorous underpaid work itself a kind of latter-day conspicuous leisure . . . for which there is rampant competition.

This is not to suggest that the two spheres are MECE; think of a prototypical Venn diagram (MECE: Mutually Exclusive, Collectively Exhaustive—perhaps the single most important concept in management consulting).

Nice piece! Lots of insights I agree with here. I've always viewed the brutal grad school culture (especially online) as a primarily function of the "elite overproduction" (Peter Turchin's thesis). The fight for scarce prestige/elite status devolves into factionalism, aggression, and deception (material concerns are important but as a secondary factor that exacerbate status anxieties when relative comparisons are unfavorable).

The biggest problem today may be the low stakes (combined with high debt), given what's happened and happening to literary culture overall: https://jakeseliger.com/2021/09/30/the-death-of-literary-culture/