Greetings Austenites—

Welcome back to Austen Math, where I quantitatively evaluate Jane Austen’s single men and her heroines’ judgment of them.

Up today: Austen’s second and perhaps most beloved novel, Pride and Prejudice. But first, a few follow-up notes to part one—

—starting with big thanks to

for featuring. And to new subscribers for joining the fun!There were also quite a few thoughtful reader comments; a couple I would like to address.

writes:May I make one suggestion? Define the primary dimensions explicitly so that ratings can be better judged and discussed.

F***ability, for example, is implicitly defined as handsomeness and charm, so I infer the dimension is referring to surface-level/first-impression characteristics but am not sure.

It’s a good suggestion. My definitions are as follows, with a lil help from Merriam-Webster (MW):

By FORTUNE (n), I mean “riches; wealth,” in line with MW 1.2, “a man of fortune.”

By MORALS (n), I mean both “ethics” and “modes of conduct,” per MW 2.2a-b, in the context of Christian Regency norms without blind deference to them.

By MANNERS (n), I mean personal bearing, air, deportment, style, etc., running the gamut of MW 1a-e, again filtered through a critical Regency lens.

By FUCKABILITY (n), admittedly not in MW, I mean sexual desirability, predominantly but not exclusively based on physical attractiveness, also including demonstrable charm, wit, and je ne sais quoi.

I will add these definitions to “Austen Math 101” henceforth, itself included in each installment for reference and standalone enjoyability.

A number of other comments were already looking forward to today’s missive, and in particular preemptively advocating for one Mr. Fitzwilliam Darcy.

writes:I admire your commitment, your originality, your math skills, and your devotion to Austen. This is brilliant. But the answer you are seeking is Darcy. The perfect man brought to life by a woman who never knew one. In other words the perfect man is imaginary.

Maybe so, Jeanne—but let’s put him to the test, shall we?

Austen Math 101

Jane Austen, arguably the greatest novelist of all time, was the author of six marriage-plot comedies of manners published between 1811 and 1817: Sense and Sensibility, Pride and Prejudice, Emma, Mansfield Park, Northanger Abbey, and Persuasion. There is rampant dispute as to how to read them. “The people who read Austen for the romance and the people who read Austen for the sociology are both reading her correctly,” Louis Menand argues, “because Austen understands courtship as an attempt to achieve the maximum point of intersection between love and money.”

Menand’s vaguely mathematical binary is directionally accurate but insufficiently sophisticated. Austen is absolutely a marital maximizationist, but her calculations have far greater dimensional depth. As such, neither the die-hard romantics nor sociologists are reading her correctly; they are equally mistaken. Over- or under-weighting any single dimension of Austenian courtship maximization amounts to a fundamental misunderstanding of what she most cunningly gets:

Austen understood status—ahem, station; that its shoring up is hardly superficial. The intrigue of the marriage plot springs not just from uncertain affection—“will they fuck”—but the balance of such possibilities with a complex and often competing set of considerations. Status questions, basically, though to the standard socioeconomic strains I would add, particularly in Austen’s case, that of moral status. Alas, fuckability is a kind of status, too.

The Austen Math model more or less directly follows my original offhand vision, ranking all of Austen’s single men across four weighted dimensions—fortune, morals, manners, and fuckability—to develop secondary insights, calculate their individual total status, and analyze their relative marital desirability. The heroines, in turn, are judged by their dimensional weighting (and to what extent it shifts over time) versus the Austenian baseline. In other words: they are judged on the soundness of their judgment. The better a heroine is at Austen Math herself, the more virtuous she is deemed.

And what of love per se? Even the most sophisticated mathematical models are simplified phenomenological representations. Indeed, this is the purpose of models. I’d argue love is largely represented indirectly by a proprietary mix of the various dimensions—but I do not claim to capture all of Austen’s complexity, let alone any universal truths.

Methodology*

I. Dimensional raw scoring of single men

Each single man is evaluated on each of the four primary status dimensions of FORTUNE, MORALS, MANNERS, and FUCKABILITY using a whole-number score of 1 to 6, one being low and six high, based on textual analysis by yours truly.

The six-point scale both allows for sufficient differentiation across Austen’s six novels and forces non-neutrality.

II. Austenian primary status weighting (baseline)

The four primary dimensions predict total status via uneven weight distribution, in alignment with the hierarchy of Austen’s values as I have long understood them:

MORALS - 40%

FORTUNE - 30%

MANNERS - 20%

FUCKABILITY - 10%

for a total of 100%.

The formula to calculate total estimated Austenian status is a basic SUMPRODUCT: D1*W1 + D2*W2 + D3*W3 + D4*W4, where D=dimensional raw score and W=Austenian weight.

III. Secondary dimension calculations

Each pair of congruous primary dimensions yields insights into a secondary dimension. At the intersection

of FORTUNE and MORALS is WORTH,

of MORALS and MANNERS is CHARACTER,

of MANNERS and FUCKABILITY is AFFECT,

and of FUCKABILITY and FORTUNE is ELIGIBILITY.

Secondary dimension calculations may be performed either via weighted or unweighted averages of their raw inputs to harness insights inclusive or exclusive of Austenian status bias, respectively.

Note the secondary dimensions get closer to viscerally lovable personal attributes—character, affect—but would be harder to directly quantify themselves (e.g.: worth is more subjective than fortune).

IV. Heroine dimensional weight variance

Each heroine is evaluated on the difference between her hierarchy of the four primary status dimensions (again per my textual analysis) and Austen’s. Like in the Austenian baseline, the heroine’s top-priority dimension is weighted 0.4, with -0.1 for each subsequent priority.

The formula for dimensional weight variance is: |W1-H1|+|W2-H2|+|W3-H3|+|W4-H4|, where W=Austenian baseline weight and H=heroine weight. I use this absolute-value “spread” calc over true squared variance for its simplicity, clarity, and sufficiency given the small size of the data set. The score will fall between 0 and 0.8 in increments of 0.2, and can be roughly interpreted as follows with regards to the heroine’s judgment:

0 - Unimpeachable

0.2 - Sound

0.4 - So-so

0.6 - Precarious

0.8 - Misguided

I.e., the lower the score, the better her judgment. In some cases, heroines’ dimensional values change over the course of the novel, in which cases I calculate both starting and ending hierarchy for comparison to estimate their development.

*Feel free—nay, encouraged—to quibble with any of this. We are here first and foremost to have fun, and banter is damn close to my definition of it.

Credentials

While admittedly an amateur Austen scholar, I am the daughter of a doting professional one—and a professional novelist and management consultant myself (see: Portrait, patents). My undergraduate degree is in English and my graduate an MBA: a thoroughly Austenian compromise. Her voice has been inseparable from that of my own conscience since I was ten years old.

Part 2: Pride and Prejudice

“It is a truth universally acknowledged, that a single man in possession of good fortune, must be in want of a wife.” So begins Jane Austen’s lightest, brightest, most sparkling novel, in a sentence so brilliant it gives reflective credit to our species. The single man of good fortune in question is Mr. Charles Bingley, who has taken the Hertfordshire estate of Netherfield—and brought his still richer friend Mr. Fitzwilliam Darcy along with him. The acknowledger of universal truth: Mrs. Bennet of neighboring Longbourn, with five daughters she’s hell-bent on marrying off: Jane, Elizabeth, Mary, Kitty, and Lydia.

Silly as Mrs. Bennet is, her schemes are not entirely without justification. Longbourn is disastrously entailed along the male line to Mr. William Collins, a distant relative and well-established clergyman who arrives in Hertfordshire not long after Bingley for the express purpose—to Mrs. Bennet’s rapturous delight—of choosing a bride from among her daughters. Bingley has already shown a highly reciprocated preference for beautiful, compassionate Jane, so Mr. Collins sets his sights on bright-eyed Elizabeth, recently snubbed by Mr. Darcy. But who hasn’t been? Darcy has swiftly managed to offend the entire neighborhood with his coldness and pride—and the tales of Mr. George Wickham, a dashing new officer in the nearby regiment, seem to confirm his ill character.

The single men

Mr. Charles Bingley; Mr. Fitzwilliam Darcy; Mr. William Collins; Mr. George Wickham

Fortune

With “four or five thousand a year,” Bingley is in possession of good fortune indeed. Though renting Netherfield, he has the means to purchase an estate—and by the end of the novel does so. Austen doesn’t mind that his money comes from trade, and we shouldn’t either. He scores 5/6 only to leave headroom for his friend.

Darcy’s income of at least ten thousand a year is adorned spectacularly by his estate, Pemberley. Pemberley is the sort of property so grand as to captivate tourists as readily as lovers—and it is when Elizabeth visits as the former that she consciously begins to regret having rejected the latter position. Clear 6/6.

As the heir to Longbourn, Mr. Collins will eventually get 2,000£ per year—but he doesn’t have it yet, and Austen says nothing to suggest Mr. Bennet likely to soon expire. Still, Mr. Collins is already comfortably situated with his clergy living; his patroness, Lady Catherine de Bourgh, is Darcy’s aunt, and nearly as great a woman as Mr. Collins suggests. He scores 3/6.

Wickham has no fortune and wasted every opportunity to establish himself. He’s a spendthrift and a gambler, forever leaving debts in his wake. 1/6.

Morals

The morals mirror the money!

Wickham is as morally impoverished as he is pecuniarily, committing, among other things, that highest of Austenian crimes. That he ultimately marries Lydia in no way mitigates his culpability in seducing her; it only happens due to Darcy’s gallant bribe. His prior attempted seduction of Georgiana Darcy is almost worse despite his failure. Rough start for Wickham: 1/6.

Mr. Collins may seem less immoral than moronic—he certainly isn’t guilty of anything on the order of seduction—but the ultimate basis of his overwrought gallantry is selfishness. His slavish admiration for Lady Catherine, introduction to Darcy, and especially his gaslighty proposal to Elizabeth are as narcissistic as they are laughable. “Mr. Collins is a conceited, pompous, narrow-minded, silly man,” Elizabeth states, though Jane thinks she goes too far. The truth probably lies somewhere in between. Mr. Collins is guilty as charged, but his sins are the product not of malice so much as insufficient self-awareness. He’s morally below average, but not truly evil—3/6.

Conversely, any faults that Darcy has are moral red herrings. As Elizabeth reasons midway through the novel:

proud and repulsive as were his manners, she had never, in the whole course of their acquaintance—an acquaintance which had latterly brought them much together, and given her a sort of intimacy with his ways—seen anything that betrayed him to be unprincipled or unjust—anything that spoke him of irreligious or immoral habits;—that among his own connections he was esteemed and valued;—that even Wickham had allowed him merit as a brother, and that she had often heard him speak so affectionately of his sister as to prove him capable of some amiable feeling;—

Her analysis is further bolstered by Mrs. Reynolds during Elizabeth’s visit to Pemberley—“What praise is more valuable than the praise of an intelligent servant?”—not to mention his direct interference on Lydia’s behalf. If Darcy is morally inflexible, he would seem to be stuck in the perfect pose. 6/6.

While Bingley’s well-placed trust in Darcy’s moral judgment is a credit to him, he is a little too reliant on the guidance of his friend; overly willing to let it override sound judgments of his own. We see this in the interpretation of Jane’s character early in the novel—and again dear Bingley gets the silver medal, 5/6.

Manners

Bingley holds his own and more here! With his “pleasant countenance and easy, unaffected manners,” the original single man of good fortune is not just the novel’s but probably the oeuvre’s most amiable man. 6/6.

Wickham’s manners are nearly as pleasing. He’s docked slightly (in shades of Willoughby) for over-familiarity, but no amount of immoral behavior ever shows their abandonment. Even in his parting scene, Austen says “Wickham’s adieus were much more affectionate than his wife’s. He smiled, looked handsome, and said many pretty things.” Have to give him 5/6.

In perhaps their only point of common ground, Messrs. Darcy and Collins prove more challenging to score.

Darcy suffers from First Impressions (the novel’s working title), namely in his pride, but “improves on acquaintance”—still more on his own turf at Pemberley. While I cannot in good conscience grant perfection, neither can I deem Darcy below average in anything. Let’s call it 4/6.

Mr. Collins’s obsequious pomposity is one of the greatest achievements in literary history, but how to evaluate his extreme formalism? His manners are cringe precisely because they are overly correct, his impoliteness springing from overwrought politesse. He’s too successful a social climber to penalize him severely—“condescended to” by Lady Catherine de Bourgh!—but I can no more deem Collins above average in anything than I can deem Darcy below it. 3/6.

Fuckability

Marry Darcy, kill Wickham—but they’re both eminently fuckable. “Mr. Darcy soon drew the attention of the room by his fine, tall person, handsome features, noble mien,” Austen says even before mentioning his income, let alone his very hottest trait: cleverness. Of Wickham: “His appearance was greatly in his favour: he had all the best parts of beauty, a fine countenance, a good figure, and very pleasing address.” 6/6 for both boyhood friends.

Alas, “good-looking and gentlemanlike” Bingley plays second fiddle to Darcy a third time—“the ladies declared he was much handsomer than Mr. Bingley”—for yet another 5/6.

And what to do with Mr. Collins? From a physical standpoint, Austen gives us only that “He was a tall, heavy-looking man of five-and-twenty.” Not particularly appealing, but it’s everything else that renders him all but unfuckable. I say “all but” only because he does get married—and presumably Charlotte holds her nose and fucks him—but the woman literally arranges her house to minimize contact. 2/6 for model purposes, on the back of negative je ne sais quoi.

Secondary dimensions & insights

Graphing their raw scores and calculated unweighted secondary dimensions, we can answer The Darcy Question posthaste:

Mr. Darcy is close to, but not quite perfect per Austen Math—which, when you think about it, holds up qualitatively. Pride is one of the seven deadly sins after all, not just a mar on his manners, but an affect and a character flaw.

That said, this chart tantalizingly dangles the possibility of perfection when we look at Darcy and Bingley, the former’s sole blemish compensated by the latter’s greatest strength. They form the perfect man together! As we will see, the same might be said of the perfect woman between Elizabeth and Jane. It would be hard to imagine a more formidable quartet.

Wickham cuts a similar figure to Willoughby in Sense and Sensibility. He’s less fortunate and better mannered, but clearly of the same archetype.

The model clearly has the hardest time capturing Mr. Collins, whose modest ring wholly fails to capture his absurdity. And yet I stand by it! Collins is matrimonially inferior to Darcy and Bingley across every dimension—but superior to Wickham, as we’ll see, when it comes to the most important ones.

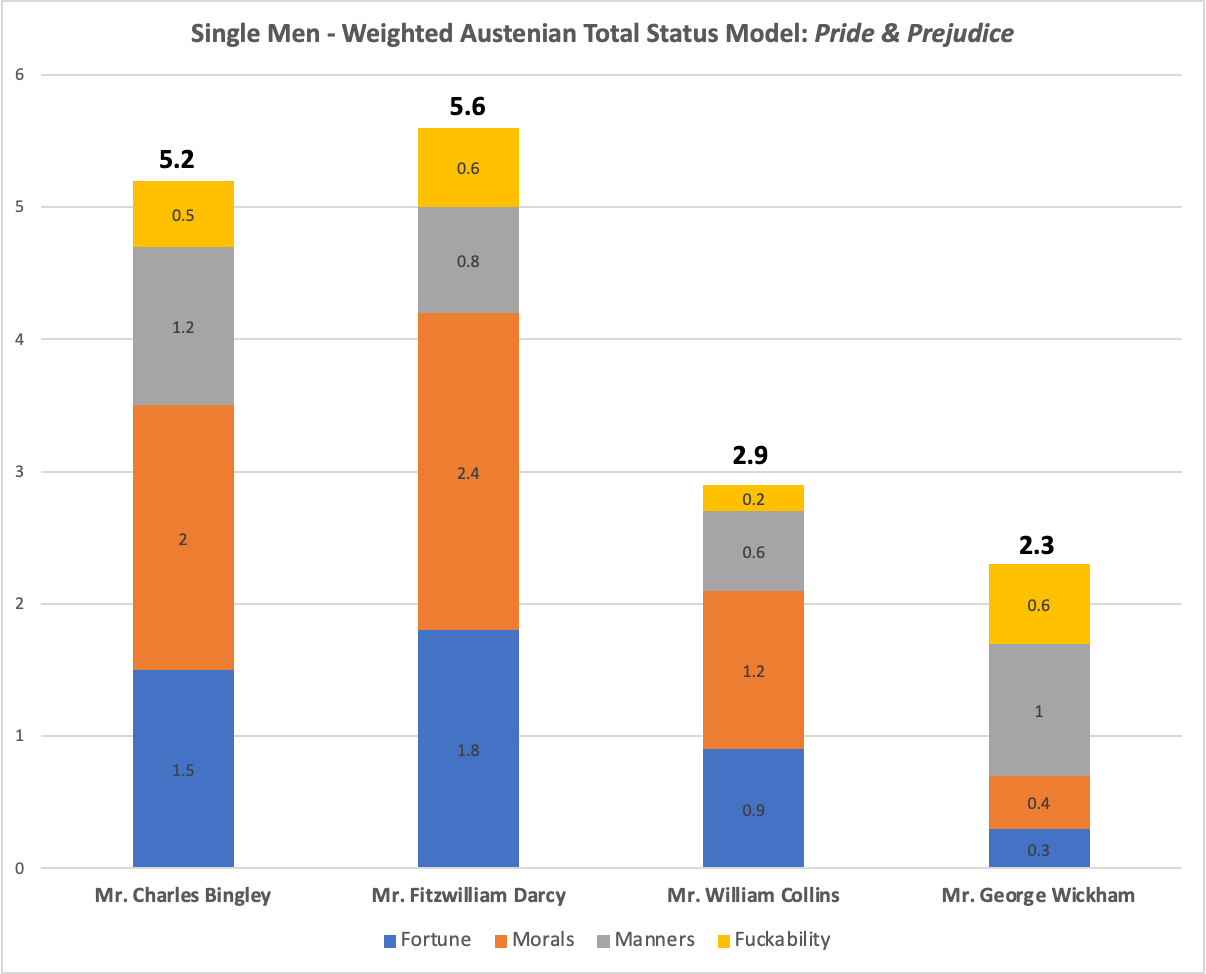

Weighted Austenian Total Status Model

Ta-da!

Darcy’s a king, Bingley a price, Collins a jester, and Wickham a dog. If this confirms your qualitative hypothesis, as it does mine, I would suggest that perhaps the model is working.

The heroines

Miss Bennet (Jane); Miss Elizabeth (Bennet)

Like Sense and Sensibility, Pride and Prejudice presents a “heroine who is right” and a “heroine who is wrong”—but the heroine who is right (Jane) is less right, and the heroine who is wrong (Elizabeth) is less wrong. Both share Austen’s moral core from the start, but deviate from her on finer points.

Though Jane is a paragon of goodness, if I were to nitpick—and I will—I’d say her positivity has the tendency to push the bounds of reason. Her Christian charity, in concert with growing up in a household where everyone is bad with money, incline her toward weighing personal comportment over societal rank—not to the point of imprudence, but implicitly:

MORALS

MANNERS

FORTUNE

FUCKABILITY

for a judgment score of 0.2 - Sound.

Elizabeth, too, suffers from her family’s fiscal irresponsibility—at least at first. I’m not saying she should have seriously entertained Mr. Collins, but her total disregard for the entail, unsympathetic if not cruel response to Charlotte’s divergent analysis, early flirtation with Wickham, and furious rejection of Darcy’s first proposal speak to the following priorities:

MORALS

FUCKABILITY

MANNERS

FORTUNE

for an initial judgment score of 0.4 - so-so.

It is not until Elizabeth sees Pemberley that her moral reanalysis of Darcy individually bleeds into her own dimensional reprioritization:

Elizabeth was delighted. She had never seen a place for which nature had done more, or where natural beauty had been so little counteracted by an awkward taste. They were all of them warm in their admiration; and at that moment she felt that to be mistress of Pemberley might be something!

FORTUNE jumps up just below morals, reducing Elizabeth’s judgement delta to 0.2 - Sound, in line with her elder sister’s. And note! Both sisters’ subtle divergence from Austen favor their husbands, with Darcy’s stiff manners loosened by Elizabeth’s gentle cheek, and Bingley’s sterling ones extra-appreciated by Jane. These boosts are quantifiable:

Our heroines choose excellent husbands—and Bingley and Darcy equally excellent wives.

Other misc. notes from this read:

It is often claimed—and I myself have referenced this—that Austen “only ever wrote from women’s perspectives.” Not true! On at least a few occasions she assumes Darcy’s. Here’s an example:

Occupied in observing Mr. Bingley’s attentions to her sister, Elizabeth was far from suspecting that she was herself becoming an object of some interest in the eyes of his friend. Mr. Darcy had at first scarcely allowed her to be pretty; he had looked at her without admiration at the ball; and when they next met, he looked at her only to criticise. But no sooner had he made it clear to himself and his friends that she had hardly a good feature in her face, than he began to find it was rendered uncommonly intelligent by the beautiful expression of her dark eyes. To this discovery succeeded some others equally mortifying. Though he had detected with a critical eye more than one failure of perfect symmetry in her form, he was forced to acknowledge her figure to be light and pleasing; and in spite of his asserting that her manners were not those of the fashionable world, he was caught by their easy playfulness.

Elizabeth is a paragon of nonchalance; I think this no small part of her contemporary appeal.

Still funny to me that Austen names Jane Bennet Jane. I know the Regency gentry was not exactly creative on the name front, but giving this character her own has always confused me! Can anyone provide insight?

How much better Darcy expresses himself in writing!

While I didn’t include them in the above analysis since they aren’t strictly heroines, Charlotte and Lydia too support the judgment model. It’s safe to say Lydia’s dimensional prioritization is antithetical to Austen’s for a judgment score of 0.8 - Misguided, while Charlotte elevates FORTUNE above MORALS to still earn the grade of 0.2 - Sound. I found myself more sympathetic to Charlotte than ever this read, perhaps because, speaking as a novelist—

Mr. Collins is the Hope Diamond of literary characterization; I will die in this mine.

NEXT UP, my own longtime reigning favorite: EMMA. Can the model hold up to the indomitable will of Austen’s most fortunate heroine? And might Mr. Knightley give Darcy, if not a run for his money, one for his weighted total status?

Stay tuned—

ANJ

One of my grad school advisors had a theory that Austen only ever named the overly sweet / near perfect characters Jane as like a joke to her family and friends! (Like Jane Fairfax in Emma!)

I predict that Knightley will actually beat Darcy's score.