Welcome new subscribers; this is the second of a two-part post. Here’s the first (coincidentally a nice introduction to quite useless):

Status (part 1)

I. Introductory I’m calling this “a diachronic canon,” with emphasis on the indefinite article, after Elif Batuman’s definition and usage of diachronicity and William Collen’s of canon. Their combination marries the antithetical twin desires underpinning my will to write: for metamorphosis and for permanence.

V. A Secondary Definition

Of status—e.g., “where you at”; the management consultant’s red-yellow-green. Big milestone to report on this front: I’ve finished my new novel. Or at least a full draft of it, which for me comprises the bulk of the (writing) effort:

I’ve been working on this book since 2019, but with extreme irregularity. The first chapter came easily enough, in between rounds of edits for The Portrait of a Mirror with my agent. I was paralytically anxious while “on sub,” however—and even after Portrait sold, made little tangible progress for a variety of reasons until my DIY writing residency last summer. In those three months of near total focus I wrote over three quarters of the novel, chipping away at the remainder since.

The chipping was by far the hardest part, the entire experience (as with the first one) in spectacular alignment with Cal Newport’s new book, Slow Productivity. My husband recently alerted me to this via

’s latest conversation with Newport about, among other things, what knowledge workers can learn from novelists. Such as? You guessed it. Jane Austen.VI. Jane Austen’s Agile Backlog

Slow Productivity’s three main tenets, “do fewer things,” “work at a natural pace,” and “obsess over quality,” are in close alignment to (real) Agile development practices and probably familiar not only to “traditional” knowledge workers like novelists and academics, but also most product and software-types. That said, the book provides a wealth of clever tactics to combat the endemic grotesqueries of performative white-collar “pseudo-productivity”—and I was utterly riveted by the section on Austen:

A popular explanation for Austen’s productivity is that she mastered the art of writing secretly, scribbling prose in bursts between the many distracting obligations of her social standing. The source of this idea was Austen’s nephew James, who in 1869, more than fifty years after Austen’s death, published a gauzy Victorian biography of his aunt [. . .]

A closer look at Austen’s life, however, soon reveals issues with her nephew’s tales of secret writing. Modern biographies, drawing more extensively from primary source material, reveal that the real Jane Austen was not an exemplar of a grind-it-out busyness, but instead a powerful case study of something quite different: a slower approach to productivity.

Aided by Claire Tomalin’s biography, Newport goes on to recount the ebbs and flows of Austen’s life and literary work:

[The Austens] inhabited a social world of “pseudo-gentry,” made up of “families who aspired to live by the values of the gentry without owning land or inherited wealth of any significance.” But it’s clear that Austen did not grow up like a character in one of her books, spending her days in a well-appointed sitting room, taking visitors while servants prepared lavish meals. She had work to do. Though Austen was a voracious reader and, encouraged by her father, began dabbling in writing at a young age, she was much too busy with the daily work of running her family’s house, farm, and school to seriously explore the craft.

I’m as fascinated by these ebbs as the flows. Austen’s gentry-adjacent youth reads awfully low-mimetic heroine / “scholarship kid at boarding school” to me—not a conducive environment to novelistic production, per se, but a highly conducive one to novelistic social research. As was, I’d wager, the decade Austen spent not writing in Bath. Meanwhile—and no surprise—her literary output proper skyrocketed when she was directly relieved of other responsibilities: from 1796-1800 in Steventon, then again after leaving Bath for Chawton in 1809:

Critically for Austen’s work, her family, wrung out from the complications and trials of the preceding years, embraced a much-needed respite by deciding to largely absent themselves from the social scene in Chawton. This was not a decision made lightly. The fact that Austen’s brother essentially owned the town, and lived in an impressive estate just a few hundred yards down the road, meant that opportunities for active social striving were likely abundant. But the Austen party wasn’t interested. “There were no dances and few dinners,” writes Tomalin, “and they remained largely withdrawn into their private activities.”

[. . .] a tacit agreement was formed that would free the youngest Austen daughter from most of the remaining household labor. She prepared the morning breakfast for the family but, beyond this duty, was free to write.

Relief from domestic duties is pretty much every novelist’s dream. Certainly it’s one of mine! (and no small part of why the new book is dedicated to my long-suffering husband). But more intriguing still is Austen’s voluntary status retreat. Opportunities for active social striving were likely abundant. But the Austen party wasn’t interested. Might this disinterest have extended beyond prioritization, beyond simply “doing fewer things”? For all of Austen’s status-savvy, her novels also make clear she understood the imitative nature of desire. I can’t help but wonder: how explicitly?

VII. Mimetic Desire

Which brings me to the big Batumanian post-publication “adventure” The Portrait of a Mirror so fortuitously prompted: my introduction to

and the work of René Girard. Luke’s nonfiction debut, Wanting, was published the same day as Portrait, and alongside Deceit, Desire & the Novel itself gave me a new vocabulary with which to discuss my own debut and art more generally.Girard’s feather-duster effect on my mind not only tidied the shelves in a way that allowed me to see what was already there; it also made room for new metaphysical objets.

I spoke a good deal about this vis-à-vis process and the novel I’ve just finished drafting at the Novitatē conference Luke hosted last November—and found myself, as my fellow panelist

recounts in his since-launched Substack devoted to “Writing Fiction After Girard,” in the minority:“To me, [Deceit, Desire & the Novel] feels very much like a guide…”

(And yet, she also mentioned that the narrator of the novel she is working on now “is a modern-day prophet, a modern-day Cassandra, and that sense of knowing too much is part of what I’m channeling into the next book.”)

What I didn’t yet realize when I said this? The relationship between my optimistic stance and sense that Girard’s genius rested more in explaining how than why. Like, I can fully articulate the mechanics of mimetic desire now—but can still be thrown for a loop by Phoebe Philo pants! I still want my new novel to sell, to write a third. Perhaps this is because I remain unconverted—though I’ll note we all tend to describe mimetic theory in terms of its “mechanics” and “laws.” And if mimetic theory doesn’t fully explain the great psychosocial why, if the Mother-Doll human quest for status encases still deeper mysteries—well, then even setting beauty and pleasure aside, literary fiction’s raison d’être seems not just intact, but extremely urgent.

VIII. Status Anxiety

Prophesy, uncertainty, probability, rarity, talent, luck: I’ve long understood these to be my second novel’s themes, along with a sense of them all being status-y and post-Girardian—but I wrote the first draft without the sort of formal framework I had for Portrait from the beginning, guided more by Cassandra’s voice and Icarus’s story. It’s only been in the last couple of weeks, with the draft out of sight on my agent’s desk, that my consultant-brain has revved into overdrive thinking about the themes’ conceptual interrelation. Specifically, under the light of a brilliant new input: Alain de Botton’s Status Anxiety (2004).

In traditional societies, high status may have been inordinately hard to acquire, but it was also comfortingly hard to lose. It was as difficult to stop being a lord as, more darkly, it was to cease being a peasant. What mattered was one’s identity at birth, rather than anything one might achieve in one’s lifetime through the exercise of one’s faculties. What mattered was who one was, seldom what one did.

The great aspiration of modern societies has been to reverse this equation, to strip away both inherited privilege and inherited under-privilege in order to make rank dependent on individual achievement—which has come primarily to mean financial achievement. Status now rarely depends on an unchangeable identity handed down the generations; rather, it hangs on performance in a fast-moving and implacable economy.

It is in the nature of this economy that the most evident trait of the struggle to achieve status should be uncertainty. We contemplate the future in the knowledge that we may at any time be thwarted by colleagues or competitors, to discover that we lack the talents to reach our chosen goals, or steer into an inauspicious current in the swells of the marketplace—any failure being compounded by the possible success of our peers.

Emphasis mine—because the last time I was this bowled over by a paragraph was reading Girard on askesis. Did I again have the great fortune to stumble upon a work of nonfiction seeming to explain my fiction back to me? Why yes, yes I did:

Our status also depends on a range of favourable conditions that could be loosely defined by the word luck. It may be merely good luck that places us in the right occupation, with the right skills, at the right time, and little more than bad luck that denies us the selfsame advantages.

But pointing to luck as an explanation for what happens in our lives has, regrettably, become effectively unacceptable. In less technologically sophisticated eras, when mankind respected the power of the gods and the unpredictable moods of nature, the idea of our having no control over events had wide currency. Gratitude and blame were routinely laid on the doorstep of external agencies, with reference made to the intervention of demons, goblins, spirits, and gods.

This time the italics are de Botton’s. Luck! He nailed it—twelve years before Robert H. Frank. Time to start putting all this together:

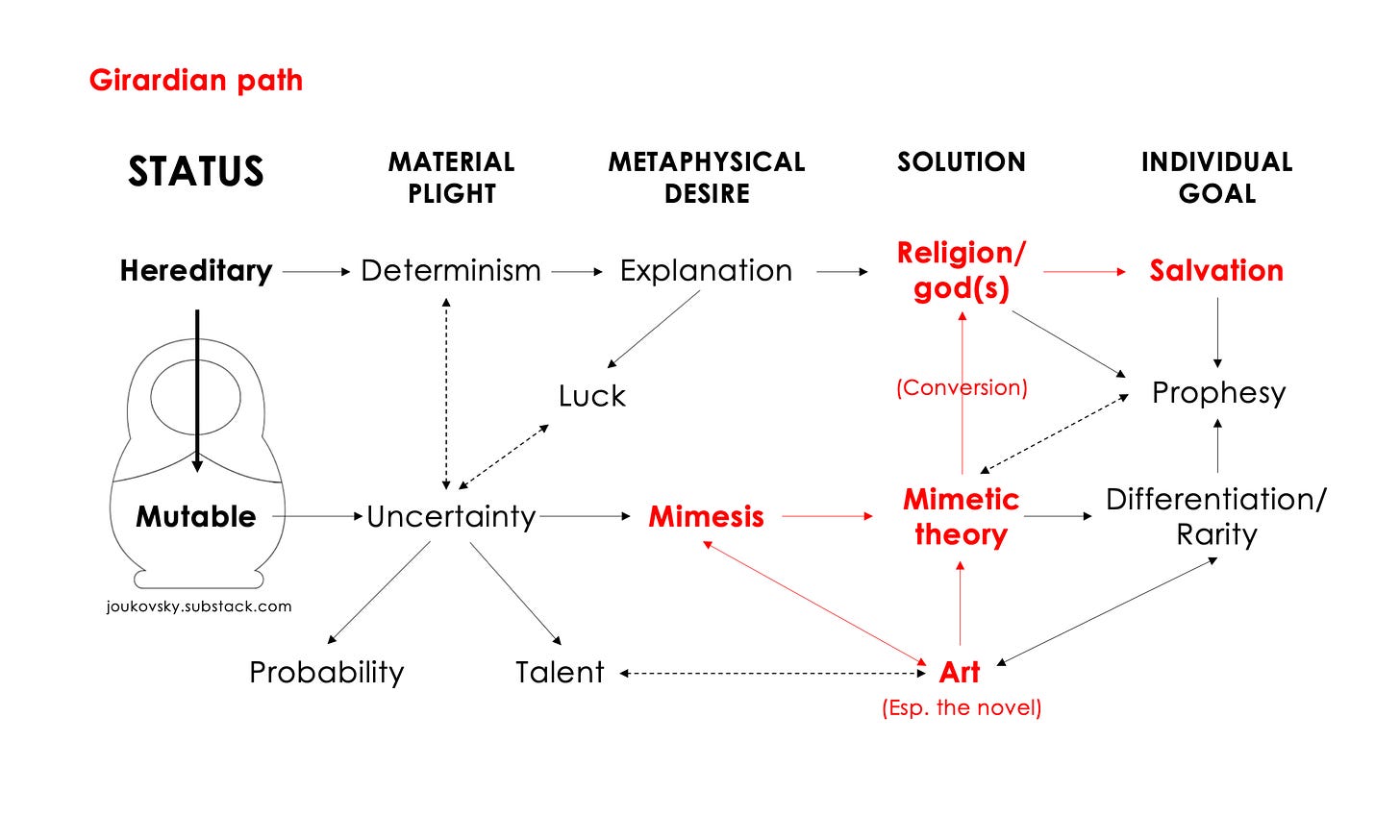

Ironically, it’s only when our “great aspiration” is—or at least has the appearance of being realized that status becomes the anxiety-provoking Mother Doll. The mere impression of mutable status will catalyze the psychological effects of uncertainty whether or not true socioeconomic mobility exists, triggering mimetic envy of those on the next rung either way. From here we can track the Girardian path:

Note Girardian conversion effectively (and, sorry, irrationally) reverts to the prior hereditary status solution. Perhaps this is why mimetic theory itself is so often (erroneously!) labeled reactionary by association? Yes, mimetic theory is bleak. But there are other viable paths forward.

De Botton, for his part, also looks to philosophy, art, politics, and Bohemia—all of which I personally find more compelling, but especially art, especially the novel. I don’t think it a coincidence that after “the middle of the eighteenth century, when the first voices began to question the heredity principle” the novel exploded in popularity, the nineteenth becoming its golden age.

If mimetic theory is presumed to be the teleology of art (red arrow pointing exclusively up), it’s easy to see why DDN would seem more novel-killer than guide. But novels also offer a self-reflexive solution to the mimetic problems they expose. Here is de Botton, after Matthew Arnold:

But far from being a mere salve, great art was in fact, Arnold argued, an effective antidote for life’s deepest tensions and anxieties. [. . .] Art, he insisted, was “the criticism of life.” [ . . . ] Given that few things are more in need of criticism (or of insight and analysis) than our approach to status and its distribution, it is hardly surprising that so many artists across time should have created works that in some way contest the methods by which people are accorded rank in society. The history of art is filled with challenges—ironic, angry, lyrical, sad or amusing—to the status system.

And who does de Botton hold up as his status-artist par excellence? Ding ding ding! Jane Austen again; he devotes an entire section to Mansfield Park. I’m already running up against the email length limit, so I’ll leave you to go read it if you want and conclude the arrow between art and mimetic theory, per the initial and ensuing chart, can very much be two-way.

IX. [Title Redacted]

I’m not quite ready to share my new novel’s title yet, but I will connect its themes to my new framework:

A few closing thoughts for now:

The new novel’s focus visibly circles mimesis and mimetic theory without deeply investigating them, because the imitative nature of desire is already taken as true.

When artistic beauty and truth are granted a third amigo, it’s usually rarity, hence their direct connection here. Of specific note, the Threnos of Shakespeare’s “The Phoenix and the Turtle, ” which immediately follows the section quoted at length in The Portrait of a Mirror: “Beauty, truth, and rarity, / Grace in all simplicity, / Here enclos’d in cinders lie.”

The link between prophesy and uncertainty, Cassandra and Icarus, is more direct than the framework makes it seem, but there were too many arrows already. Alas, the perfect is the enemy of the good.

The question of free will haunts the heavily-debated link between determinism and uncertainty—and this is where Robert Sapolsky’s influence comes in (who also did a great recent interview with Sam Harris, by the way). For my part, I want to connect the illusion of free will to art’s deceptive honesty—to the choice plot and novelistic truth. I’ll leave you with Plutarch on the matter, in a passage that has become immensely dear to me:

But tragedy blossomed forth and won great acclaim, becoming a wondrous entertainment for the ears and eyes of the men of that age, and, by the mythological character of its plots, and the vicissitudes which its characters undergo, it effected a deception wherein, as Gorgias remarks, “he who deceives is more honest than he who does not deceive, and he who is deceived is wiser than he who is not deceived.” For he who deceives is more honest, because he has done what he promised to do; and he who is deceived is wiser, because the mind which is not insensible to fine perceptions is easily enthralled by the delights of language.

Natasha writes, "Which brings me to the big Batumanian post-publication 'adventure' . . . "

- Every time I think I'm going down a rabbit hole with Natasha's writing, I'm glad for the trip. She is an intriguing provocation! Amazing. Read for yourself if you haven't already.

I do think Girard can be read as deterministic (which in my view is a problem--Luke has written or is writing about this) and also maybe as upholding a more irrational, Kierkegaardian take on faith. But those questions aside, one point that strikes me here is the idea of still wanting a certain pair of pants or to write a novel despite grasping the mechanics of mimetic desire. This is a very relatable problem for me as in my own experience as well, fluency in Girardian theory confers no immunity from Girardian behavior. But then again, who wants anything to do with a sort of conversion that would make novelists we like to read want to stop writing novels??