Hello hello, two quick things first:

I’ll be at the Novitate Conference in DC on November 3 alongside the novelists Brandon Taylor and Trevor Cribben Merrill, discussing the impact of Girardian thought on contemporary novel-writing

ICYMI check out Cecilia Rabess’s recent piece in the WSJ, “The Rise of the MBA Novelist”—I was delighted to receive a shout-out because it’s excellent

Okay, on to the theme, my favorite theme, the theme that keeps on giving (and giving (and giving (…))). I’ve been collecting recursive cartoons for a while now, nearly a decade, and will be going full Bob Mankoff on the subject today.

Here is my absolute favorite:

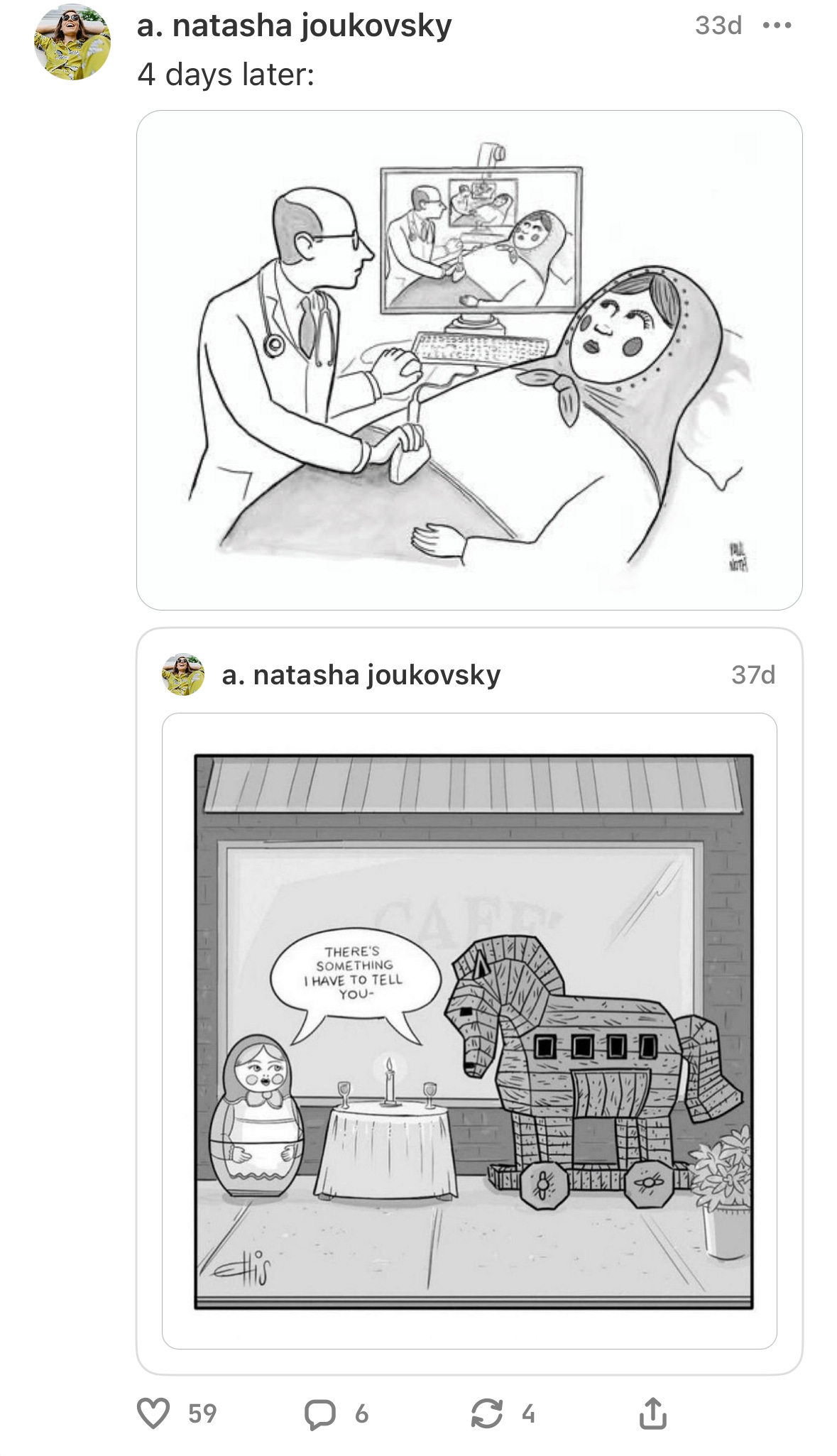

My second-favorite is, shall we say, a natural extension of the first:

Once I started sharing these I couldn’t stop—because others seemed to enjoy them, yes, but also because I couldn’t resist completing a nested frame story loop. It was almost too easy, I realized, when such a disproportionate share of my collection involved slutty matryoshka dolls.

At the risk of committing humor’s greatest sin, I’m going to indulge in a little analysis as to why.

Intellectual superiority

Recursive cartoons in general tend more toward intellectual than emotional appeal. They are—the good ones anyway—clever, and make us feel clever in their cleverness. Perhaps this is why the New Yorker is so especially partial to them, and why I am so especially partial to the New Yorker’s:

Infinite absurdity is structurally embedded, conveying more with less. There is an almost minimalist sort of sophistication at play—and yet any elitism is offset by the humility of the medium. Crucially, recursion is invoked conceptually without any self-reference to the hifalutin word, which would immediately plunge it into the realm of nerd-jokes. Such line-toeing is analogous to art like Seinfeld that illustrates mimetic desire without entirely pulling back the curtain, that reveals our too-human foibles without the pain of their personal implication.

Moral superiority

Traditional matryoshka dolls are luridly visual and recognizable, but I don’t think this fully explains their iconographic dominance across the recursive-cartoon sub-genre. The most Russian thing about me is my name, and this alone has been enough to provide ample first-hand experience with the stereotypes about Russian women. The matryoshka doll’s, ahem, anatomy does little to refute and much to reinforce these—and to the intellectual pleasures of recursion, she adds the perennial moral pleasures of slut-shaming.

The innuendo frequently eclipses sex and reproduction itself with almost welfare-queenesque implications:

Our moral superiority is likewise bolstered in being offset, in this case by the fact we’re feeling superior not to another person, but a doll—and not just any doll, but a conspicuously modest, folksy one. A literal peasant. She’s abstract, too; removed a layer further from real women than, say, Barbie. The matryoshka doll is just representative enough of a woman for us to revel in our moral high ground, but not enough to feel any remorse for her shame. We can ridicule and objectify with her with impunity, because she is so obviously an object.

Superior superiority

I submit: the platonic form of feeling superior is the feeling’s self-obfuscation. Hence why recursive cartoons are viewed as delightfully clever, yet obsession with recursion qua recursion snobby and pretentious.

If you made it this far, thanks for proving me wrong!

ANJ

i would read a 600 page book on this topic if you wrote one. and if it had a tiny 600 page book inside it. Like arabian nights, but an analysis. Analysis nights.

One for the collection https://xkcd.com/1739/