Hello friends,

When I met

at the Substack Writers event in DC this past Friday (which was lovely; thanks to and for hosting), I almost immediately suspected we would stay in touch. Not only was Sarah a delightful interlocutor, but she had just published an essay I recognized even from the first few lines as a worthy heiress to an ancient and illustrious tradition, going back at least to Castiglione:For the past decade or so, I’ve been referring to this illustrious tradition as the study of manufactured nonchalance. Instead of linking to my original piece on the subject (which predates Substack, isn’t appearing correctly in the app, and is apparently uneditable), I’m going to re-share it in its entirety here, followed by some further comments.

A brief history of manufactured nonchalance (2017)

A friend sent me this article in the New Yorker today by Rachel Monroe about "the bohemian social media movement" #vanlife, yet another glamour-based aspirational lifestyle turned carefully-curated visual product. The foundational abstract idea of this particular strain is "freedom," but the exterior narrative follows the same inevitable trajectory as every other such phenomenon, ending in manufactured nonchalance. Monroe describes the #vanlife photo shoot process towards the end of the piece:

Smith had a particular image in mind: King sprawled in the back of the van, reading a book about Ayurveda with Penny nestled next to her, and an “Outsiders” decal featured prominently on her laptop. As Smith shot from the front seat, King tried a few different positions—knees bent; legs propped up against the window—and pretended to read the book. “Sometimes it’s more spontaneous,” she said apologetically.

“It’s about storytelling, and when you’re telling a story it’s not always spontaneous,” Smith said. “Lift your head up a little bit more, look like you’re reading.

Our cultural obsession with nonchalance and this particular breed of mythmaking long predates Instagram, as does the desire to manufacture it. You can trace the seeds of the idea back to the tale of Pygmalion in Ovid's Metamorphoses ("The best art, they say, / Is that which conceals art"), but the first explicit reference I'm aware of is in Baldassare Castiglione's The Book of the Courtier, where it goes by the name sprezzatura. His is still perhaps the best definition of manufactured nonchalance out there:

refers to this same passage in The Power of Glamour and returns often to the impression of "effortlessness" as a central manifestation of glamorous visual communication. Building on Castiglione, she argues:I have found quite a universal rule which in this matter seems to me valid above all other, and in all human affairs whether in word or deed: and that is to avoid affectation in every way possible as though it were some rough and dangerous reef; and (to pronounce a new word perhaps) to practice in all things a certain sprezzatura, so as to conceal all art and make whatever is done or said appear to be without effort and almost without any thought about it.

Sprezzatura makes its possessor seem like a superior being and the observer feel momentarily transformed, enveloped in that aura of confidence and competence. Like the glamorously streamlined surfaces of the Chrysler Building, however, sprezzatura is a facade—a form of artifice that demands care to create and maintain.

Manufactured nonchalance appears frequently in fiction as well. A neat little example from Anna Karenina:

Anna had changed into a very simple cambric dress. Dolly looked attentively at this simple dress. She knew what such simplicity meant and what money was paid for it.

In Ian McEwan's Atonement, Cecilia Tallis even more explicitly seeks the same effect:

Relaxed was how she wanted to feel, and at the same time, self-contained. Above all, she wanted to look as though she had not give the matter a moment’s thought, and that would take time.

Again and again, nonchalance is something we want to build with images but tear down with words. On some level we all understand it is an illusion, so why do we keep falling for it?

Social media has created a more robust strain. Sprezzatura is no longer just for courtiers; the art which conceals art has been democratized and demographized, with a feed for whatever your subjective tastes require. It is a glamorous distraction, but it's also a personal expectation.

Check out this no-holds-barred exposé from Rachel Cusk's 2014 novel, Outline:

He was, in effect, manufacturing an illusion, no matter what he did, the gap between illusion and reality could never be closed. Gradually, he said, this gap, this distance between how things were and how I wanted them to be, began to undermine me. I felt myself becoming empty, he said, as though I had been living until now on the reserves I had accumulated over the years and they had gradually dwindled away.

#vanlife is a metonymy of our culture, of our very world right now; we are all increasingly defined by our roles in this simulacra-based digital ecosystem. Disillusionment with it, the realization that "freedom," or whatever else you fetishize, is staged—this is the crisis of our time for people who aren't stuck in Syria.

In retrospect, I should have referenced the Gone Girl monologue (the book came out in 2011, the movie, 2014), but fortunately, this is precisely where Sarah’s essay picks up the thread, charting one of manufactured nonchalance’s latest metamorphoses:

The effortless internet girl, our faceless, nameless, charismatic persona, became the cool girl. I’d like to think it’s a reclamation of the term from the masculine version, though. “She’s so cool, she’d drink a beer with us” turned into “she’s so cool, her vintage Miu Miu is to die for.” It’s everything re-packaged, centering the female gaze instead. The cool girl or at least the version we look at today, caters to what women find interesting, enviable, ready to drop thousands of dollars to achieve. The kicker is the cool girl, the internet girl, is fake. Almost no one that puts themself into these boxes on the internet exists like that in real life. They exaggerate, play it up, know how influential their content will be but continue the charade. Young girls used to be told that they needed to be pretty, that everyone would want to be them when they were beautiful, and now they’re meant to be interesting, cool, and enigmatic. Regardless of how it’s packaged, a girl will never escape the world telling her what she’s meant to be.

The durability of this idea independent of its packaging was precisely what I was looking to illustrate in what my 2017 piece was building towards: the distinction between Vivien and Diana’s approaches to “effortlessness” in The Portrait of a Mirror. “Vivien Floris was the sort of woman who seemed so perfect she almost failed to pass the Turing test, the most impressive aspect of her algorithm being her apparent unconsciousness of her algorithm’s effect,” while:

To say that Diana was clever, animated, refreshingly frank—these were apt, but also insufficient. Her surface had a shiny, stylized quality, to be sure, but there was an underlying honesty of effort, an honesty almost unheard of in privileged circles. There was an implicit social risk in trying too hard, and a kind of bravery in it, in deliberate rebellion from manufactured nonchalance. And yet there was a nonchalant air to this very rebellion. Was not such honesty part of her gambit? The truth was such a foreign concept, it had its own kind of affectation.

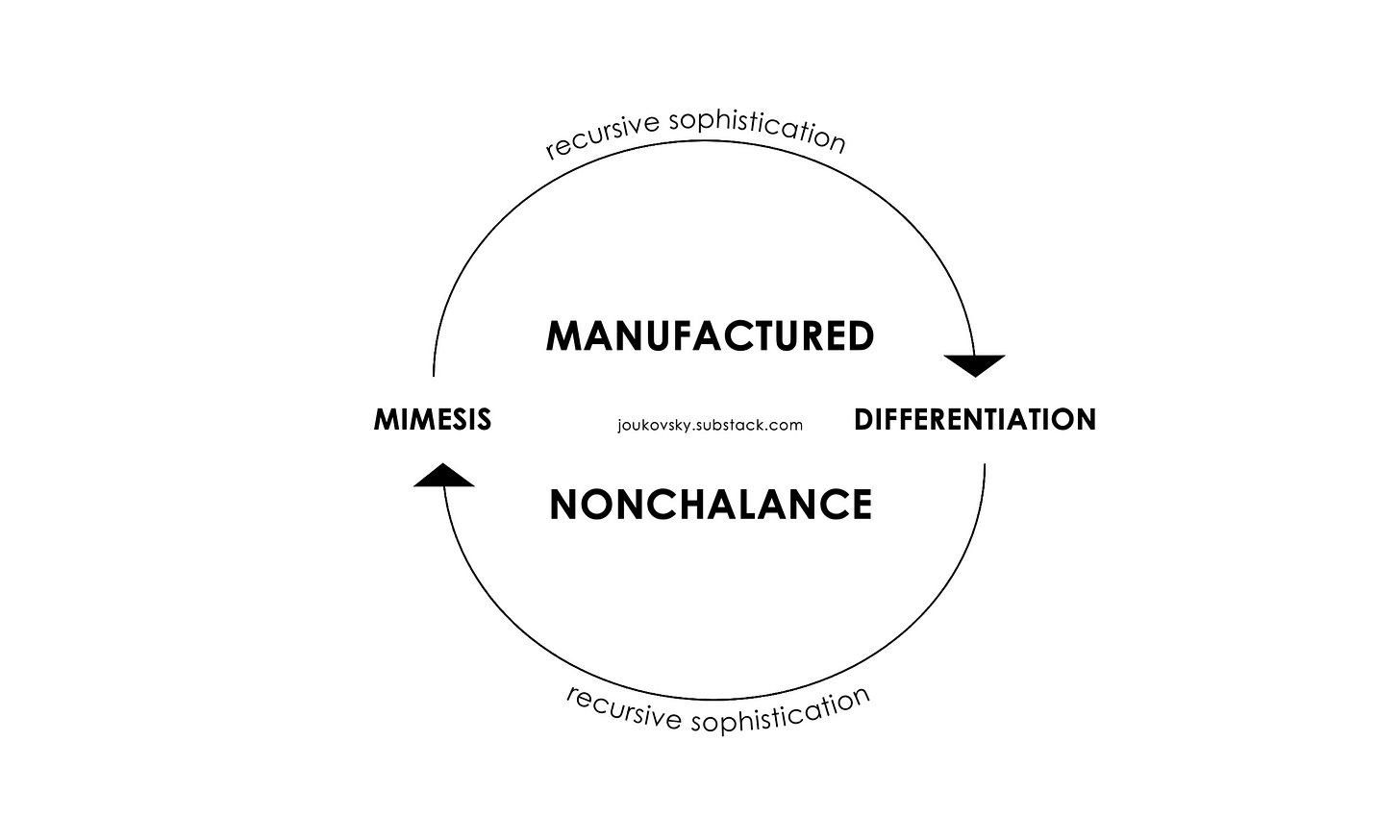

The project of selfhood has, over the course of the past couple millennia, become an increasingly sophisticated recursive battle between mimesis and differentiation, between working to copy the prevailing signals of effortlessness and “effortlessly” rebelling against them. As Sarah puts it: “‘I’m different from the rest’ a chorus of voices call out, indistinguishable as Reformation-clad bodies blend into one being.”

But there was another line in Sarah’s piece that my mind even more sharply italicized, embedded in the paragraph I first quoted: everyone would want to be them.

While I’ve long thought of manufactured nonchalance and the mechanics of Girardian metaphysical desire as being closely related, it was in talking to Sarah and reading her piece that I first caught the light of a potentially more causal relationship; of manufactured nonchalance being a sort of primal gateway into the black hole of inquiry I’ve been pursuing for . . . most of my life—in my novels, my nonfiction, on Substack—which (with credit to

), I want to call secular metaphysics.Secular metaphysics, the study of the fundamental nature of existence without relying on religious or supernatural explanations, is probably the truer centrifugal force of my interests even than status:

What is the ultimate pursuit of secular metaphysics? I think it must be some kind of mortal enlightenment—which at moments I feel I’m on the precipice of glimpsing, but have not yet properly achieved. And if this is so, I can’t help but think the appreciation of manufactured nonchalance—the crushing yet liberating realization that it is manufactured—is the first step towards it.

Thanks for reading,

ANJ

I’m so grateful to have met you!! This piece is so brilliant and I’m honored to be included here 💘 I’ll be thinking about secular metaphysics and manufactured nonchalance for a long time and I’m excited to dive in during many more chats with you!!

"Our cultural obsession with nonchalance and this particular breed of mythmaking long predates Instagram, as does the desire to manufacture it." — this part is so important! it seems like even within the growing awareness of manufactured nonchalance, we're relieved to be able to blame it on instagram, just so we can pretend like it's out of our control because the big bad internet tricked us. Thank you for sharing this!!

Also side note, a DC meet-up sounds lovely and I'll have to join next time!