I exist in two professional worlds that people love to separate, but have more in common than either would like to admit.

On the one hand, I’m a literary novelist; on the other, a senior manager at a huge publicly traded company. It’s the former that naturally gets more airtime here, but in terms of my lived experience, these realms exert fairly comparable forces on me and influences on each other.

Corporations are stories written by lawyers—I’ll come back to this later—while literary authors are incentivized to behave like corporations. Today that means:

All published novels are products (even those that are also art)

So brands are helpful to sell them

So we want to build brand—that is, author—awareness

But novels take so long to write! And edit (and edit (and edit))! They are resource-intensive and cognitively expensive, with risky, winner-take-all ROI

So we look for “short term wins”—essays! book reviews! podcasts! listicles! Twitter! Instagram! Substack!

The “short term wins” take . . . longer than expected—even as these urgent but lower-value projects take priority over long-range important ones

So novel : non-novel output ratios tend to decrease over time

And fewer literary authors will derive their status and success primarily via books

What I am after here is not a contrary but complementary angle, focused less on the publishing industry’s evolving market dynamics than the isomorphic connection between a culture’s high-literary output and mainstream corporate dynamics writ large—that is, the analogic formal relationship between literary author and corporation within any given culture.

Why? Because I think they’re pretty analogous!

To use ARX-Han’s cleverly borrowed terms: while editors are indeed generally agents, literary authors are their own principals—and, as such, subject to a scaled version of many of the same structural forces as not only publishing companies but basically any corporate entity acting as a principal in the same contemporaneous cultural system.

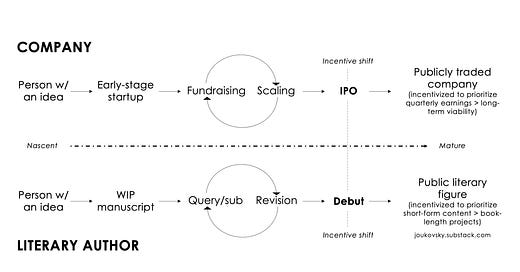

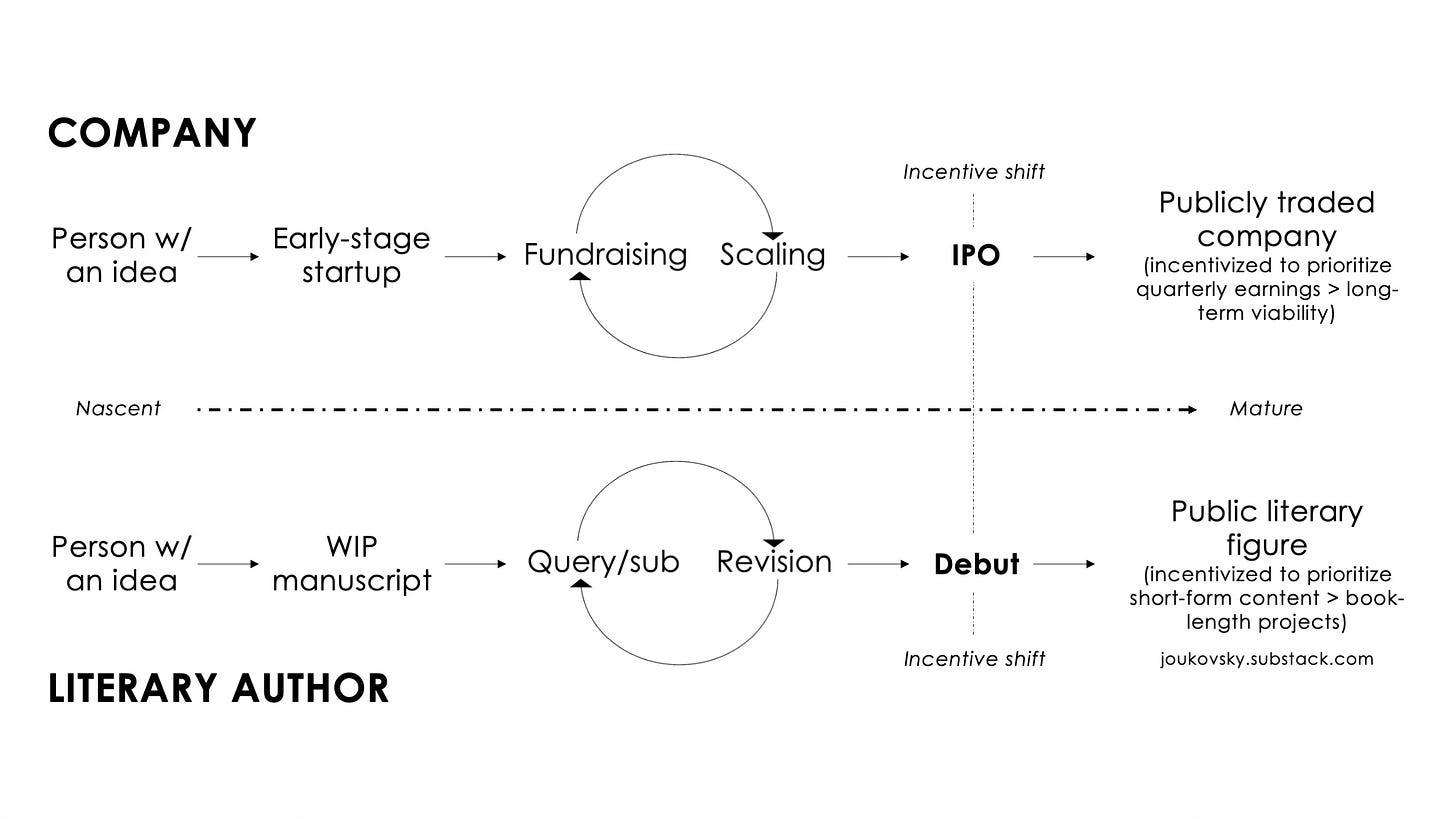

Isomorphic contemporary maturity models

Consider the maturity model for a successful twenty-first century company:

A person or small group has an idea for a cool product, and starts trying to build it. Something works—or it doesn’t, and they pivot—which is fine; they’re small and nimble. The long-term vision becomes compelling enough to be selected for Y Combinator. They raise a series A, series B, scaling operations with each round. After a few years of impressive growth, they’re ready to cash in and go public. It’s exciting—but also invites greater scrutiny. Specifically: on a quarterly basis. The new, transformed principal entity—shareholders—want to see predictable incremental growth every earnings call. The second big, unproven product management’s been working on seems risky. Operational changes are now hard and cumbersome. What are they doing to squeeze profits on the first?

You can see where I’m going with this.

I wasn’t being glib with this note—the maturity models map so cleanly!

Isomorphic evolutions in the last ~75 years

The essays I linked to above cover a lot of what’s changed in the literary world since the “heydays of the 1950s and 1960s,” as Yingling calls it, when the Roth-Updike brosefs were building their titanic careers.

What was happening in the corporate arena at the time? There was a similar sort of long-term stability—and the first glimpses of future quarterly returnification.

If the ‘50s and ‘60s were the golden age of the bro-lit author, so too were they those of the “company man.” The guys who would get out of college and remain loyal agents at, like, GE, for their entire careers, gradually climbing the corporate ladder in every assurance that their principal entity would eventually give them a gold watch and a pension in return.

Meanwhile, the S&P 500 was founded in 1957. Walmart, Comcast, Best Buy, Visa, and Mastercard were all founded during this period. Many of the companies I think we would eventually come to quintessential associate with “fast modern culture” in

’s 2024 evolutionary framework:

We can start to see another scaled isomorphism here, between the principal evolutions of companies and literary authors and the broader evolution of our culture:

What is echoing what here?

Despite their absence from his original chart, Gioia largely blames the corporations for starting this—specifically, the big tech companies I think we might call “dopamine corporations” that were largely founded around the same time Jonathan Franzen published The Corrections in 2001. Google and PayPal in 1998; Meta in 2004—that is, at the height of “fast modern” Walmart-BestBuy-Visa life.

The new wave of companies predates the new wave of culture. Which begs the question not only what is being founded now, but what exactly is a company?

Corporations are stories

The best explanation I have ever come across explaining the true nature of corporations is from Yuval Noah Harari’s children’s book Unstoppable Us: How Humans Took Over the World (which my son loves and I find better than his books for adults). In it, he tells the story of McDonald’s incorporation:

Do you know how the McDonald’s Corporation was created in the first place? It wasn’t created when Richard and Maurice McDonald laid the first brick of their first restaurant or fried their first burger. It wasn’t created when the first customer walked in and paid them a dollar. No, it was created when a lawyer performed a bizarre ceremony and told everybody a story: the story of the McDonald’s Corporation.

To tell the story properly, the lawyer first had to put on special ceremonial robes—also known as a suit. If you’re going to tell people an important story, you need to look impressive. Then the lawyer opened a lot of old books written in a language that nobody except lawyers understands: legalese. [. . .]

The lawyer searched through these old books for the exact words needed to create McDonald’s, then wrote them down on a beautiful piece of paper so they wouldn’t be forgotten. Then the lawyer held up the piece of paper and read the story out loud to a lot of people.

Of course, nobody could see the McDonald’s Corporation, or hear it, or touch it, or smell it. But still, all the adults were convinced that the McDonald’s Corporation really did exist because they heard the story that the lawyer told, and they all believed it.

And I guess that’s why I married a lawyer.

Seriously though, if we want to understand the causal landscape of something, I think it not just prudent but necessary to consider the recursive causal impacts of its many layered, analogic systems. But I am now venturing too close to another, more formal project of mine—so this seems like a good place to stop.

Thanks for reading,

ANJ

You might also enjoy:

People would rather have prestige than babies

Regardless of whether and to what extent you think it’s an issue, global fertility rates are declining, especially in developed nations. There has been a great deal of public discourse recently as to why.

and—

Your mastery of intricate analysis is far beyond anything I can hope to match—your framing razor-sharp and intellectually generous. But still, I wonder whether the contrast between “literary author” and “publicly traded brand” overstates what may be a repackaging of an old tension. Haven’t writers always had to balance artistic ambition with public performance, even if the mediums have changed? The stakes feel timely—not entirely new, but brought into sharper focus by the clarity of your rendition here.

You’ve sharpened the terms of the debate in a way I recognize every time I myself write—even this response, which I want to be both honest and compelling to someone other than me.

We are selling ourselves in everything that we do. Im working very hard to focus on connecting with people rather than merely extracting money from them.