Hi friends,

If I was in New York this week, and I do regret that I am not, I would be at Christie’s ogling the late Paul Allen’s jaw-dropping art collection. The masterpieces going to auction November 9-10 could easily have birthed an institution akin to the Barnes Foundation. (Instead, “Pursuant to his wishes, the estate will dedicate all the proceeds to philanthropy.”)

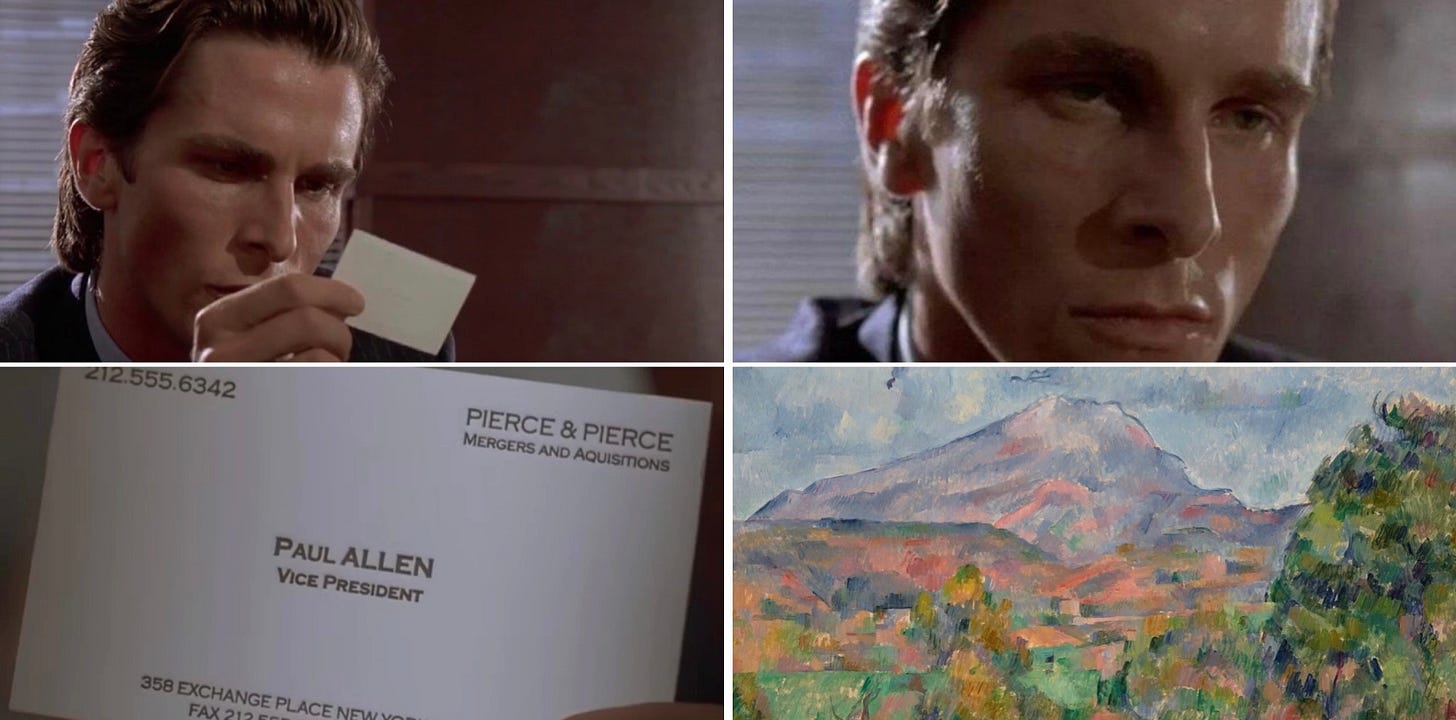

Even just looking at the collection online has been provoking in me something like Patrick Bateman’s seething envy of his fictional namesake’s business card.

You might think the real Paul Allen, being both the multi-billionaire co-founder of Microsoft and now dead, an unlikely mimetic rival for me (“who does she think she is!” etc.). Admittedly, I don’t envy the dead part—though the dead part may also be precisely what renders possessing art of this caliber such a slippery thing.

What exactly constitutes the ownership of a masterpiece? A name inked into the provenance has limited value in and of itself. The true value comes with what that ink implies: unfettered private access to look. And this, the real privilege of ownership, is inherently temporary, if nothing else by that great equalizer: death.

This kind of art has never graced my personal residence, but the nature of my first career nonetheless afforded me quotidian personal communion with such works, in several cases strikingly similar ones to pieces in Allen’s collection. His Cézanne Saint-Victoire, pictured in the meme above, is from the same series as the Philadelphia Museum of Art’s, which formed the centerpiece of the 2009 exhibition I was initially hired to support, Cézanne and Beyond. I saw it daily for months, as I did the Noguchi sculpture garden when it opened the following year (the Allen Collection has a beautiful one).

Almost by necessity given its layout, the Metropolitan Museum of Art’s tolerance for unsupervised staff in the galleries was even more generous; the access I had still astonishes me. The Met has some (and very often the best) of everything, but of particular note: a study for La Grande Jatte, the painting Seurat recursively nests into the little Les Poseuses that is perhaps the crown jewel of the Allen Collection. (It’s worth mentioning the full-scale version is at the Barnes Foundation.)

The Met was still closed to the public on Mondays for the better part of my time there, and it became my favorite day of the week. If I didn’t experience ownership proper traipsing through the galleries alone or in what often felt like the even greater privacy of my best friend’s company, then there was at least a sense of profound, if momentary guardianship.

The alone part of this, the private in “unfettered private access to look,” is critical, I think, to both the general impulse to collect and my mimetic pretensions here specifically. There is a thrill to viewing art in spite of, or sometimes even due to the surrounding crowd; this we might call the thrill of looking (sometimes it gives way to the thrill of being seen). But there is another distinct pleasure rooted expressly in the thrill of others’ inability to look. As Jonathan Franzen writes in Freedom: “But nothing disturbs the feeling of specialness like the presence of other human beings feeling identically special.”

If you’re tempted to dismiss this as horribly elitist then fine, lol; it will not be the first time that particular accusation’s been levied at me. But I’d wager the thrill of others’ inability to look is more a product of basic human psychology than personal moral failing. Think of the curious tendencies it helps to rationalize, from the historical practice of installing great art behind elaborate curtains to the use of photo-editing apps to remove background passersby.

Anyway. If I had a billion dollars lying around, I would be doing some bidding this week, starting with le petit Les Poseuses.

Here are a few of the other masterworks I’ve been coveting:

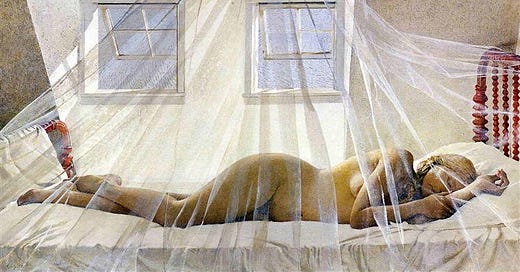

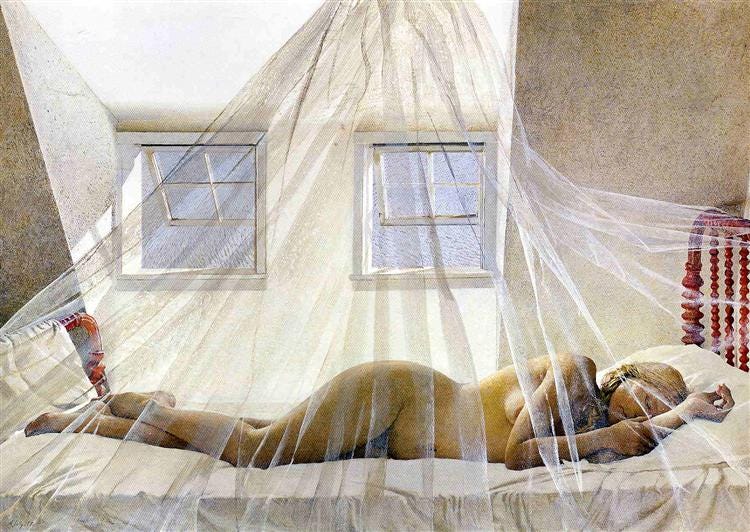

Lot 33: Andrew Wyeth, Day Dream, 1980

One word: drapery. Okay, two: virtuosic drapery. Who am I kidding? This is a painting that begs for ekphrasis even as it transcends it, that legitimately merits ultra-deluxe words like “gossamer” and “diaphanous”—the sort of words writers love so much they’re tempting to force. There’s the blue sky through the window; my god, the light. If Proust could have seen Day Dream he would have spent two-thousand words just describing its effects on the beaded headboard. And this is to say nothing of our subject herself, fully in the tradition of les grandes odalisques yet somehow thoroughly modern. It’s my favorite painting of the collection.

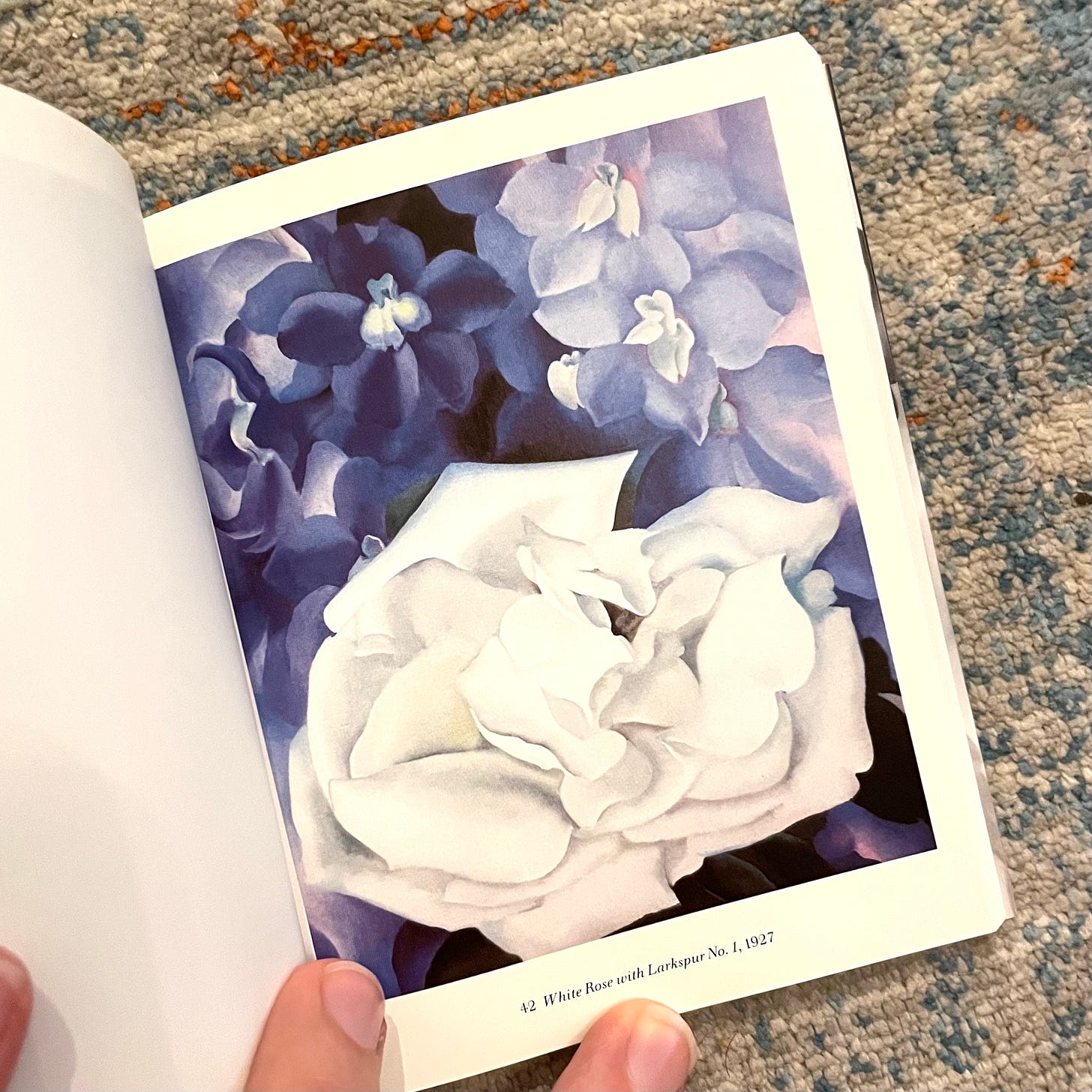

Lot 9: Georgia O’Keeffe, White Rose with Larkspur No. 1, 1927

The Allen Collection has four O’Keeffes in it, but I’m disproportionately drawn to this one, having immediately recognized it from the little book of One Hundred Flowers I’ve had since childhood.

Lot 108: Alberto Giacometti, Applique modèle "masque aux serpents", version B, 1934

If you’ve read my novel, you know I want the Medusa. This piece is straight out of Art & Myth: Ovid’s Heirs.

Lot 6: Paul Signac, Concarneau, calme du matin (Opus no. 219, larghetto), 1891

I think Paul Allen probably loved pointillism for the much the same reason I do, for the way it visualizes the fusion of art and science, the mathematics of beauty, the beauty of mathematics—and here, their union in the natural world. This seascape is at once ebullient and restrained, expressive and technical. I love the way the orange boat draws your eye above the waterline first before drifting down into its gently undulating reflection, more beautiful still.

Lot 105: Yayoi Kusama, Infinity Nets (T.W.A.), 2000

My love for the queen of recursion endures, and I am agog at the signature dotty splendor of this billowing, cloudy painting. Check out the photo showing its scale in the lot essay . . . I need whoever buys this to invite me over.

Lot 115: Rene Magritte, Stimulation Objective, 1938-1939

Another fascinating, recursive piece. I love how the little pitcher and apple replicas surreally float on and inside their larger counterparts at once.

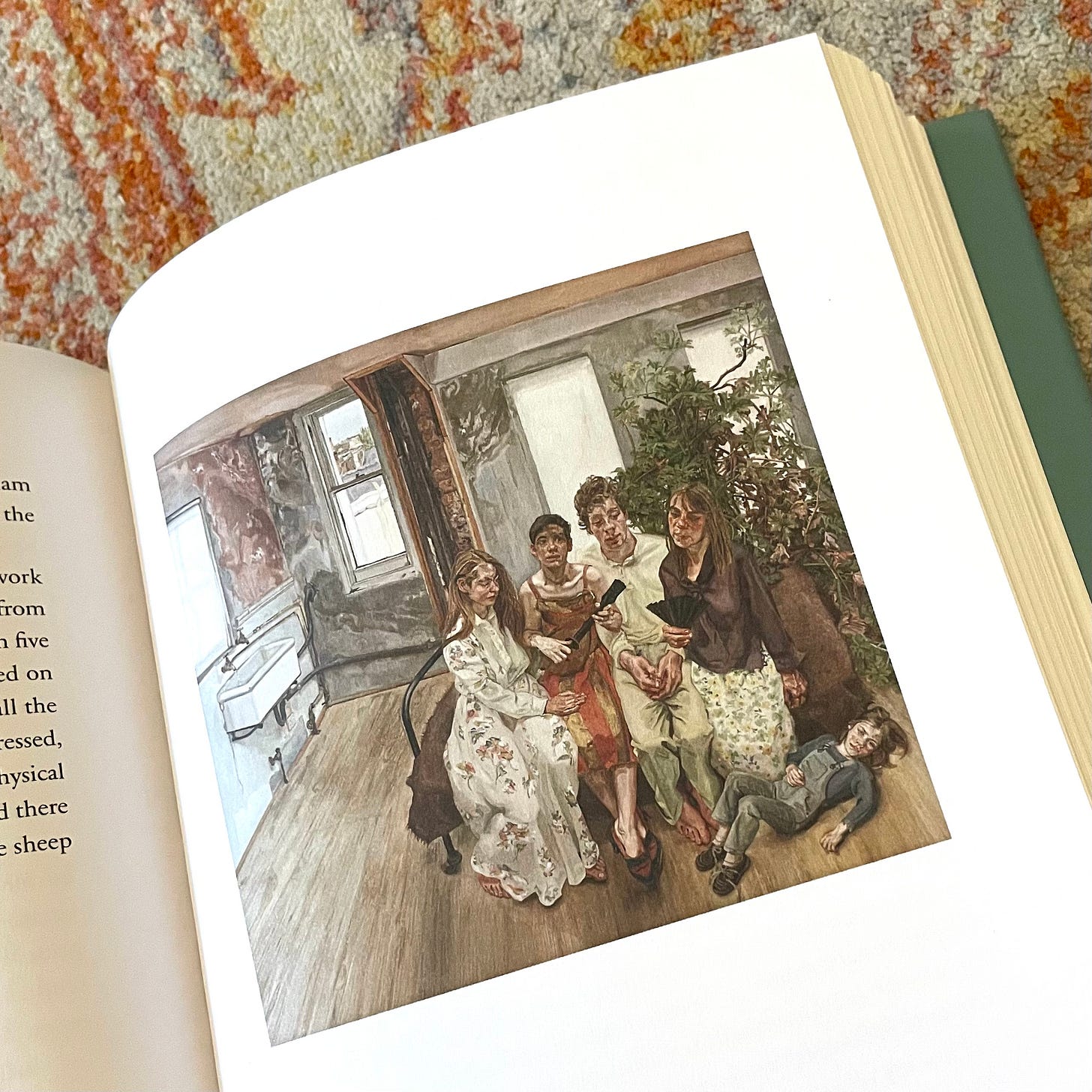

Lot 34: Lucian Freud, Large Interior, W11 (after Watteau), 1981-1983

Okay, I nearly fell out of my chair when I saw what may be Lucian Freud’s magnum opus on offer, an echo-painting that struck me forcibly when reading Celia Paul’s luminous memoir, Self-Portrait:

. . . he would work intensely on a detail and the painting would gradually grow outwards from this point [. . .] The forms grew bigger as he progressed, so that we appear to be squashing up next to each other. Despite the physical proximity, each figure seems locked into her or his private world and there is no emotional empathy between us. We look lost and isolated, like sheep huddled together in a storm.

Lot 46: JMW Turner, Depositing of John Bellini’s Three Pictures in La Chiesa Redentore, Venice, 1841

I had the chance to see this painting in the late aughts when it was on loan to the Tate Britain for Turner and the Masters. While I’m sure the little caption read private collection, I still can’t quite conceive of anything from that show being allowed outside a museum.

I’ll stop myself here, with the final note I also really like this Agnes Martin, this Gursky print, and this gorgeously colored illustration of Krishna slaying Bakasura.

If you’re in New York, please go see this stuff . . . and send me pictures so I can Day Dream.

ANJ