“Of all the dangers in life, there is perhaps none more treacherous than getting precisely what you want.”

It’s been a little over two weeks since the publication of The Portrait of a Mirror, and one of the most interesting questions I’ve fielded to date is whether this line from Chapter XII holds true—how it feels to have gotten what I wanted, given the novel’s marked suspicion of it. Has publishing a novel proved to be treacherous?

Yes—and no, but mostly yes. In departing from the land of pure possibility, something is always lost (“only unwritten novels are perfect” &c.). While I was always expecting to mourn my success in this sense—in the sense that it represents the preclusion of other novels and lives—I’ve also been caught off guard by hidden and unpredictable dangers to publication of a more concrete, quotidian nature. The sort of things that, in my day job, I might list on a slide titled “Current-State Challenges” and suggest a slew of initiatives to address. And still, I’m thrilled that the novel was published, to call myself an author; there have been unexpected quotidian benefits as well.

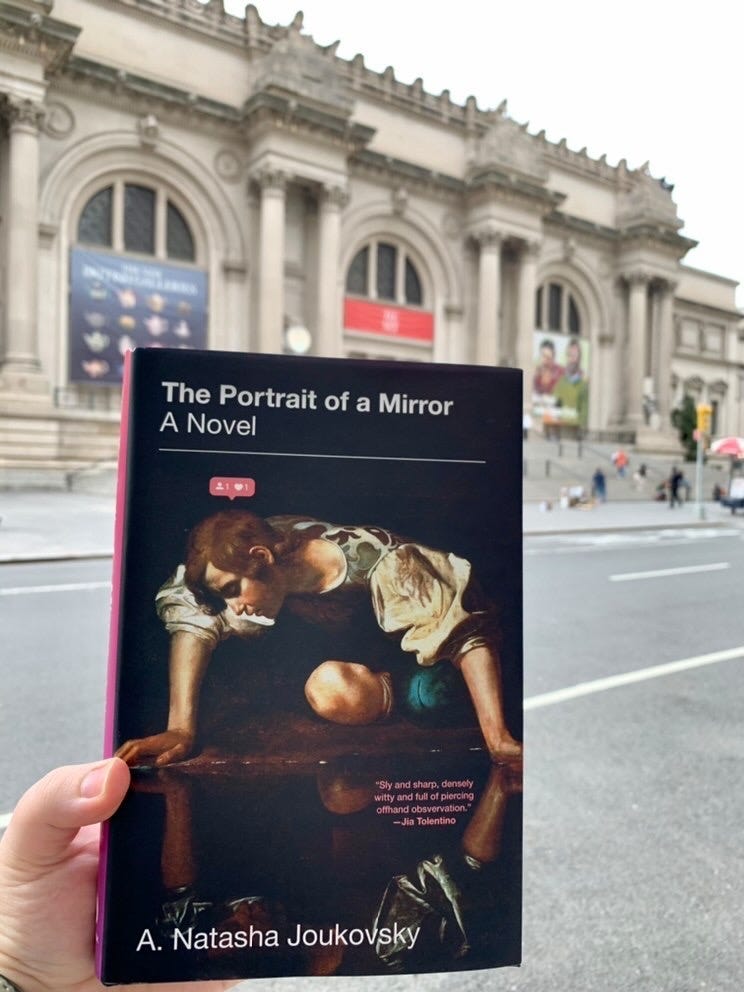

Let’s start with those, first among them being connecting with other authors whose work I admire. I wrote about a few of their books in this piece for Electric Literature, and the virtual events I did with Lauren and Jia were a pure delight. I’ve loved hearing from readers, too; I read every review and enjoy even the unflattering ones (special shout-out to the NetGalley reviewer who said the novel was “almost Aaron Sorkin-like, if Aaron Sorkin also did a mountain of blow before sitting down to write”—I love you). Then there has been seeing The Portrait of a Mirror, a novel about art, become a physical work of art itself. The beauty and care with which Abrams/Overlook published it exceeded my loftiest expectations, and every time I go to look something up I’m newly impressed by its crisp design and production.

Still, the achievement does seem to mock me. Publishing is as vulnerable to the hedonic treadmill as anything else, and with every accolade, the goal posts keep shifting. And, happy as I’ve been with my own publisher, I have to admit significant disappointment in the industry collectively—in its insular dogma and groupthink; the way it kowtows to lunacy based off a few tweets. The same thing that’s happening to people in this country is happening to books, with a few stratospheric winners hollowing out the midlist. How these anointed few are chosen seems to have more to do with luck than literary quality—not to say that many of them aren’t high quality (many are!), but rather that literary quality seems to be an independent factor from their selection as winners.

I’m reminded of the summer of 2011, when I worked at the Metropolitan Museum of Art during the Alexander McQueen: Savage Beauty exhibition. It was a marvelous show; when I first saw it, I was thoroughly impressed. But over the course of its run, it underwent a kind of public metamorphosis: the exhibition itself was eclipsed by the line to see it. I had to enter Savage Beauty a couple of times during its final days for my job; it was crowded and hot and noisy and uncomfortable and difficult to disentangle McQueen’s garments from the fervor surrounding them. In a world of finite attention, paying attention to what others are paying attention to is often a reasonable heuristic, but there was something about the mania for McQueen that went too far with it, a blind, sheeple quality that actually changed visitors’ critical evaluation of the exhibition. Because who wants to have waited in line for five hours to have been underwhelmed? Our brains are hardwired to justify our choices.

For as often as I’ve noticed this same phenomenon in the decade since, I’ve been unreasonably disheartened by publishing’s focus on the line over the exhibition—that the interest in new books seems to be determined more by this very interest than by what they contain (in some cases, it seems not even reviewers have bothered to find out). As the New York Times put it a while back: “best sellers sell best because they’re best sellers.” If you’ve read The Portrait of a Mirror, by now you will have noticed that the underlying theme here is . . . recursion. It’s a special kind of mindfuck to see your novel out in the world, yet entrapped by its own pet obsession. And it’s not just me—you can feel a similar anxiety emanating off half the authors on Twitter, the pressure to go viral, to orchestrate and project “buzz” in an industry that’s snobby about all the wrong things. We’re systematically incentivized to perpetuate the recursive system that’s undermining our art: to be cheery and inoffensive; to hype not only the books we think are best, but those that are gaining the most traction, regardless of literary quality or whether we’ve read them, in hope of reciprocation. My concern is less that we’re all afraid to share our salty opinions (though this does sadden me) than we’ve managed convince ourselves the fluffy, sycophantic ones reflect our actual taste.

Not that the big winners necessarily fare any better. One thinks of David Foster Wallace—of his mental health, sure, but also how all the attention on the attention itself transformed his legacy into shorthand for a particular brand of literary douchebaggery. “As it has been said, the mistakes we male and female mortals make when we have our own way persist in raising wonder at our fondness of it.”

Or, at least this is what I tell myself as I refresh Amazon and Goodreads, wondering if my novel can enchant the algorithm, pining for the treachery of success.

Very best,

Natasha

https://natashajoukovsky.com

I recently discovered your substack through Liv Strat and am really enjoying your writing! Looking forward to getting a copy of your book -- though I wish I would’ve in 2021, of course! (I blame the publishing “algorithm” but also I had a newborn in 2021 so it could’ve been my fault for missing it!)

As I go through a lengthy bout of writer's block, I find myself thinking about the reasons for writing. Most of my writing over the last 5+ years has been fan fiction, poetry and essays. I tend to write for myself, because it is how I express myself best, and the end product is merely words on a screen, perhaps downloaded or printed out by my audience. It has never been a dream of mine to self-publish in book form, or by a publishing house. The act of writing has been enough usually, and I found that bringing a thought or story to completion was all I needed to feel I succeeded. Of course, I wish for my work to be read, and appreciated, but in this culture where we produce so many works, my need to produce work to be consumed has been lost. I believe the words, hopefully sooner than later, will return and I will carry on.

On another note, I am so very pleased and excited for you, enjoy whatever joy you experience from this event in your life. :)