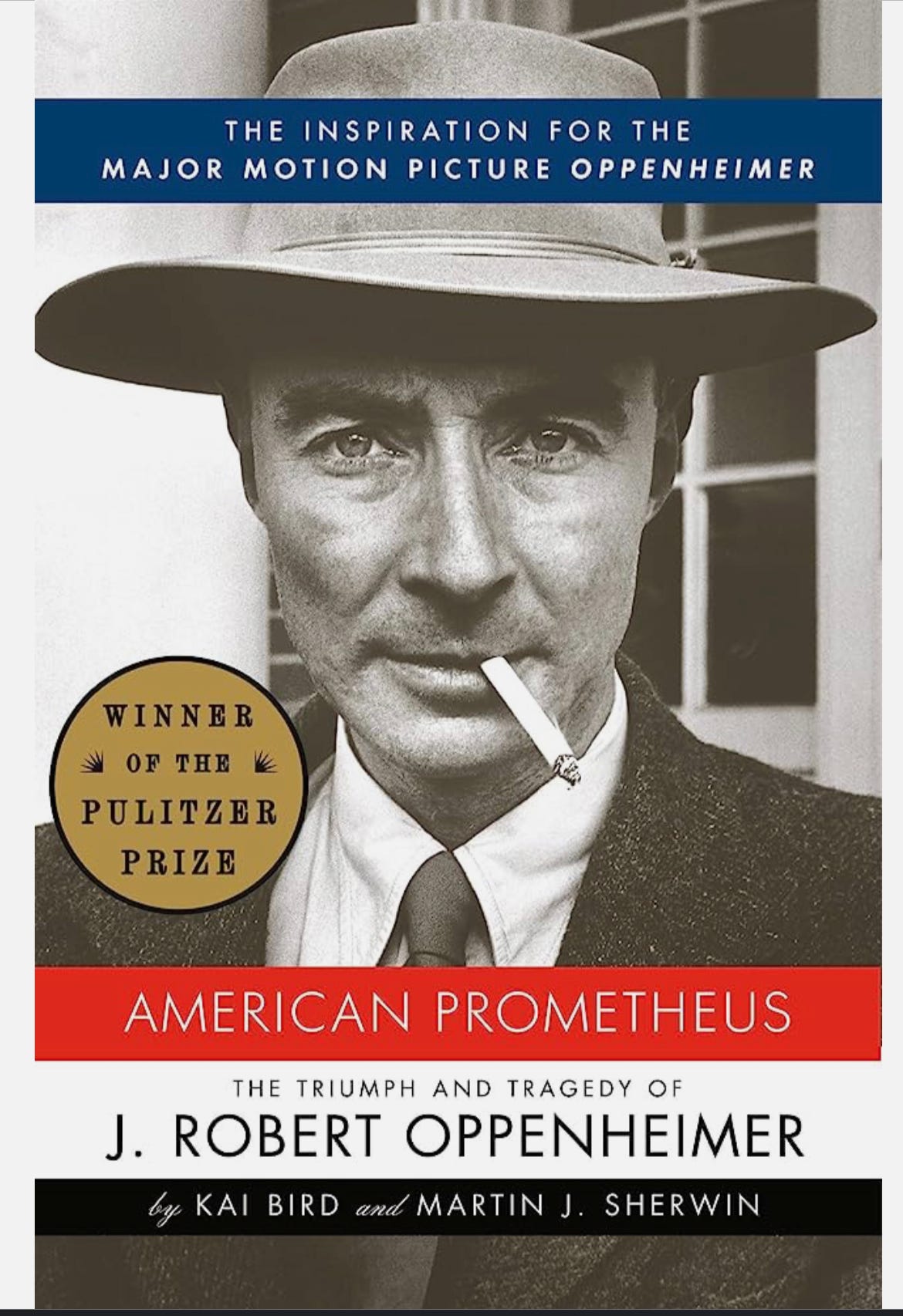

No spoilers—and only a few notes on the films themselves. I thought both were impressive: smart, visually stunning, well-acted. Oppenheimer pales in comparison to American Prometheus, the epic biography by Kai Bird and Martin J. Sherwin, but Barbie is way better than the doll. It was delightful being back at the movies, seeing non-franchise films succeed, even if both owe material debts, from the Pulitzer to the plastic. This continuum gets closer to my subject today, and what’s fascinated me most about the Barbenheimer phenomenon: the simultaneous emergence of two films of such similar quality yet polar opposite vibes, each branded to differentiated damn-near perfection.

I am powerless, in such circumstances, to resist the siren song of a 2x2, my friends:

It’s hard to imagine anyone doubting Christopher Nolan’s Oppenheimer could be smart—Oppenheimer was smart. It’s a biopic of a theoretical physicist, of a famous man by a famous man. And it’s smart! A smart movie about the father of the Big Bomb that’s branded with appropriate darkness and seriousness.

It’s great that so many people are recognizing Barbie can be—Barbie is—also smart. I’d argue this represents less a new phenomenon than the furthest extremity of smart, Barbieland art. Think of Gentlemen Prefer Blondes, which was published in 1952, and hit theaters the next year—the year before the Oppenheimer security hearing. More recently, there’s been Mean Girls, Bridesmaids, Hey Ladies!, Happy Hour, et al. So there was actually a pretty well-established pink path for Greta Gerwig, not to diminish her kudos for going the biggest and pinkest and anti-ist that which Barbie is also so earnestly, unavoidably pro.

The underestimation of smart Barbieland art is still a problem on the misogynistic fringes—and for a few moralistic “intellectuals” whose inability to appreciate self-subversive art strikes me as a serious lack of imagination! I feel true pity for anyone who did not laugh at Barbie’s last line. But anyway. I think there is a significantly bigger challenge female artists—and particularly novelists—face than Barbieland’s underestimation: its over-embrace. The tendency, that is, for publishers to push Barbie-ish branding onto art by women that falls decidedly more on the Big-Bomb side of things.

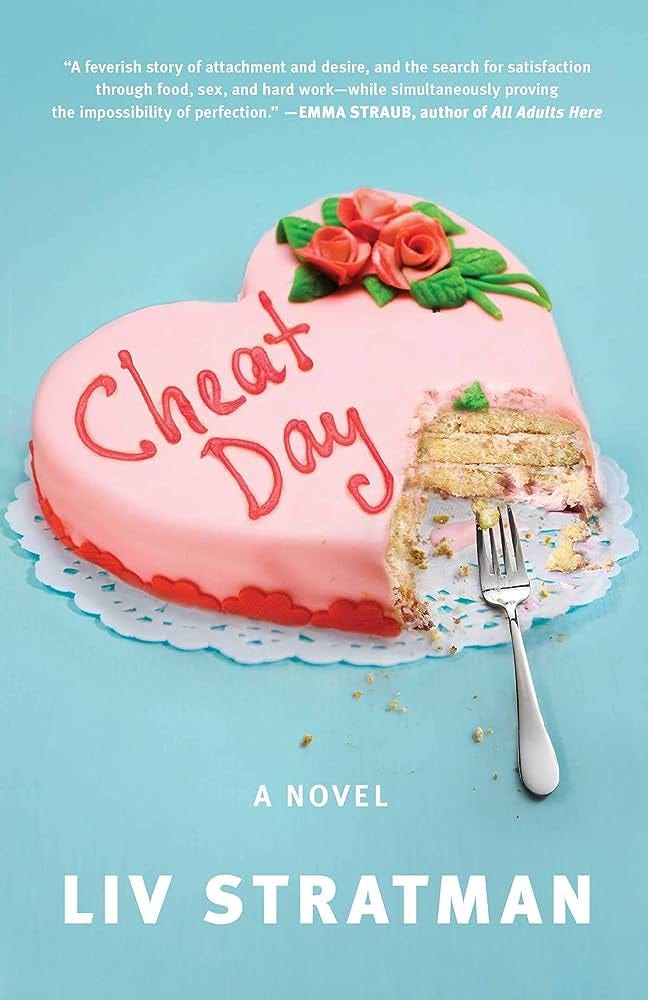

Consider the cover for Liv Stratman’s 2021 novel, Cheat Day:

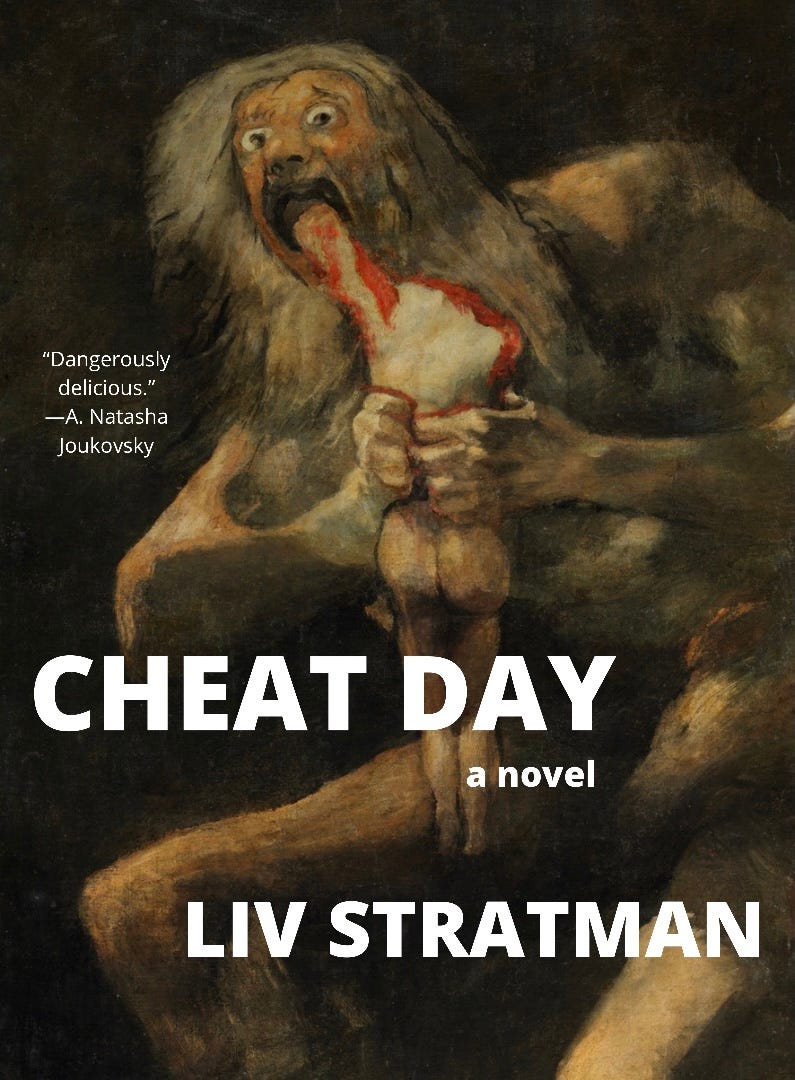

Does this, dear reader of my snobby, useless newsletter, look like a work of art that would appeal to you? I’d wager not. It looks like a commercial romantic comedy, perhaps even a romance novel. I don’t mean this as an insult to either genre. Frothy pink branding isn’t an artistic insult, incongruous branding is. Yes Cheat Day is set in a bakery—but it’s a dark social satire! Unquestionably left of the Y axis on the 2x2. With Liv’s permission, I’m going to share the alternative cover I made to cheer us both up shortly after publication:

Please note this is not like that YouTube video that recuts The Shining into a romcom trailer. I genuinely think my version would be a better cover. What I mean by “better” here is that it would more accurately reflect the novel’s tone and target audience. I loved this book. And yet, on account of its branding, I doubt I would have ever considered reading it had I not become friends with Liv first. Her brazen hilarity and candor is wholly reflected in the novel itself—just not its cover.

Is branding superficial? Yes. But it is deeply so. I keep thinking of this keen line in Ben Purkert’s recent novel The Men Can’t Be Saved: “‘All brands are lies,’ she replied sharply. ‘Some just happen to be true.’” Indeed. And it matters which ones happen to be true. In Purkert’s book, they’re talking about car safety, how the safest and unsafest manufacturers have an equal incentive to build their brands around, well, safety. It’s all the same bogus for the branders, but individual consumers can be materially—existentially—effected by which they drive.

There’s an analogous metaphysical phenomenon going on with novels and Barbieland branding. Whether or not this is true (and I have no reason to either believe or disbelieve it) there is a widespread perception in publishing that 80% of readers—specifically, people who buy books—are women. Barbieland branding has been so successful in selling commercial novels that there’s this well-intentioned but deeply misguided impulse to foist it onto every book with any conceivable angle to justify it, thinking this will help sell more copies. The impulse is way stronger when the author is a woman.

Now, for Barbieland narratives, this is fine! It’s great, actually. Because you are setting up the right readers—the novel’s target audience—for an enjoyable experience in line with their narrative expectations.

The problem with incongruent branding, with swathing Big-Bomb narratives in pink and cyan, is that you don’t actually get the boost of Barbie. You get Just Ken.

Just Ken narrative branding is bad for literally everyone involved. Authors feel misunderstood, over-gendered, and anxious their book won’t reach their intended audience. Which it often doesn’t, because it’s working to attract readers in the mood for, say, a light beach read. And as a reader, when you want a frothy romcom and get a dark social satire? The Kenergy is so off!

The book starts getting negative ratings and reviews on Goodreads, on BookTok—because the wrong people are picking it up. Readers who would actually enjoy it, meanwhile, if they weren’t discouraged by the branding already, are further misled by the low ratings, skewed by readers the book was never intended to please. Sales falter, making everyone at the publisher unhappy—and devastating the author, especially if they’d expressed their initial concerns; asked for elements to lean more Oppenheimer, but been convinced that Ken would commercially perform.

I’ve used Cheat Day to walk through the crux of my argument because it’s a particularly salient example, but Just Ken narrative branding is widespread. I saw elements of it earlier this summer with

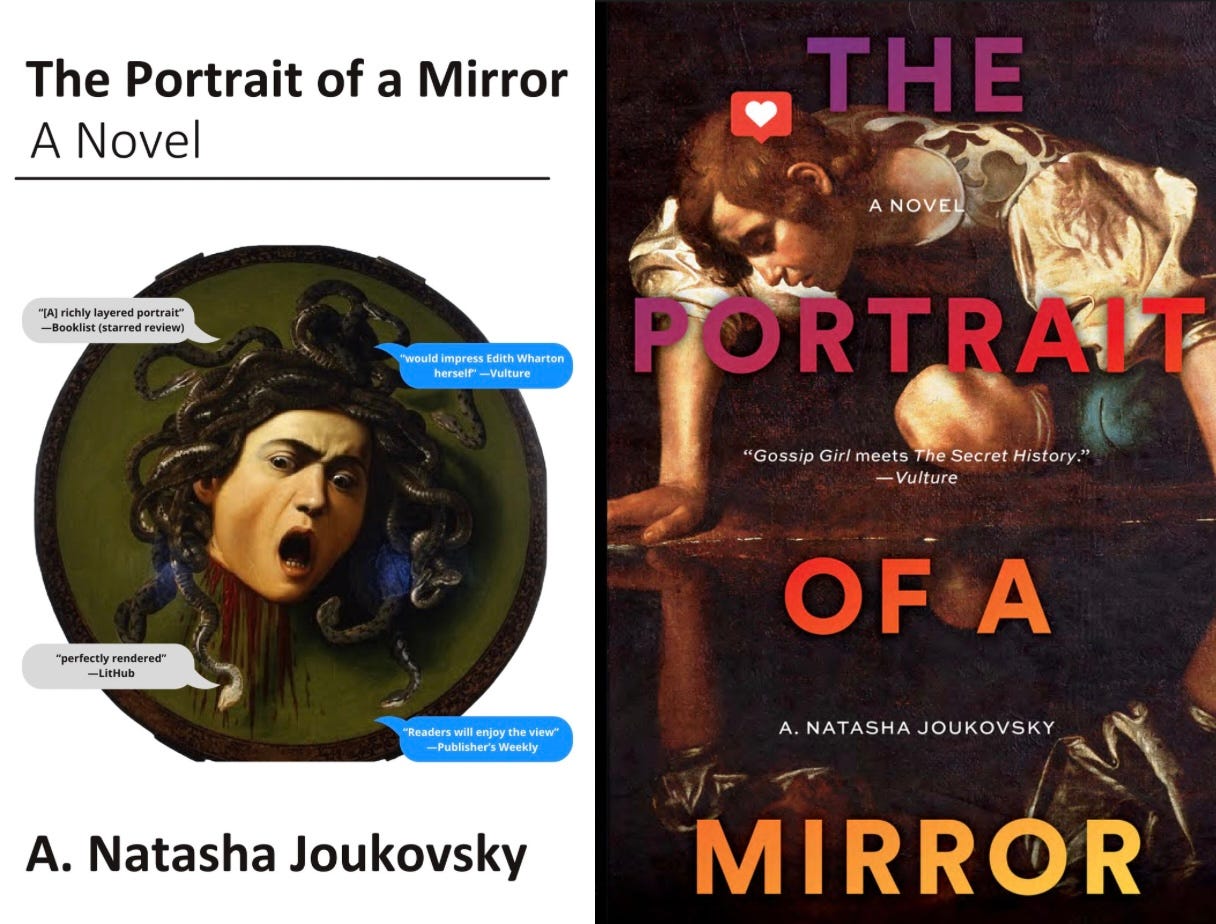

’s gorgeous literary novel Maddalena and the Dark, which—clue—has Dark in the title(!), but is about teenage girls. To a lesser extent, I’ve faced elements of it myself. While I loved the hardcover design for Portrait, the closely-related concept my agent and I proposed for the paperback was a given a hard no:I still like the lighter paperback remix I got quite a bit, but please note just how much pinker and frothier it is than the rejected Medusa one!

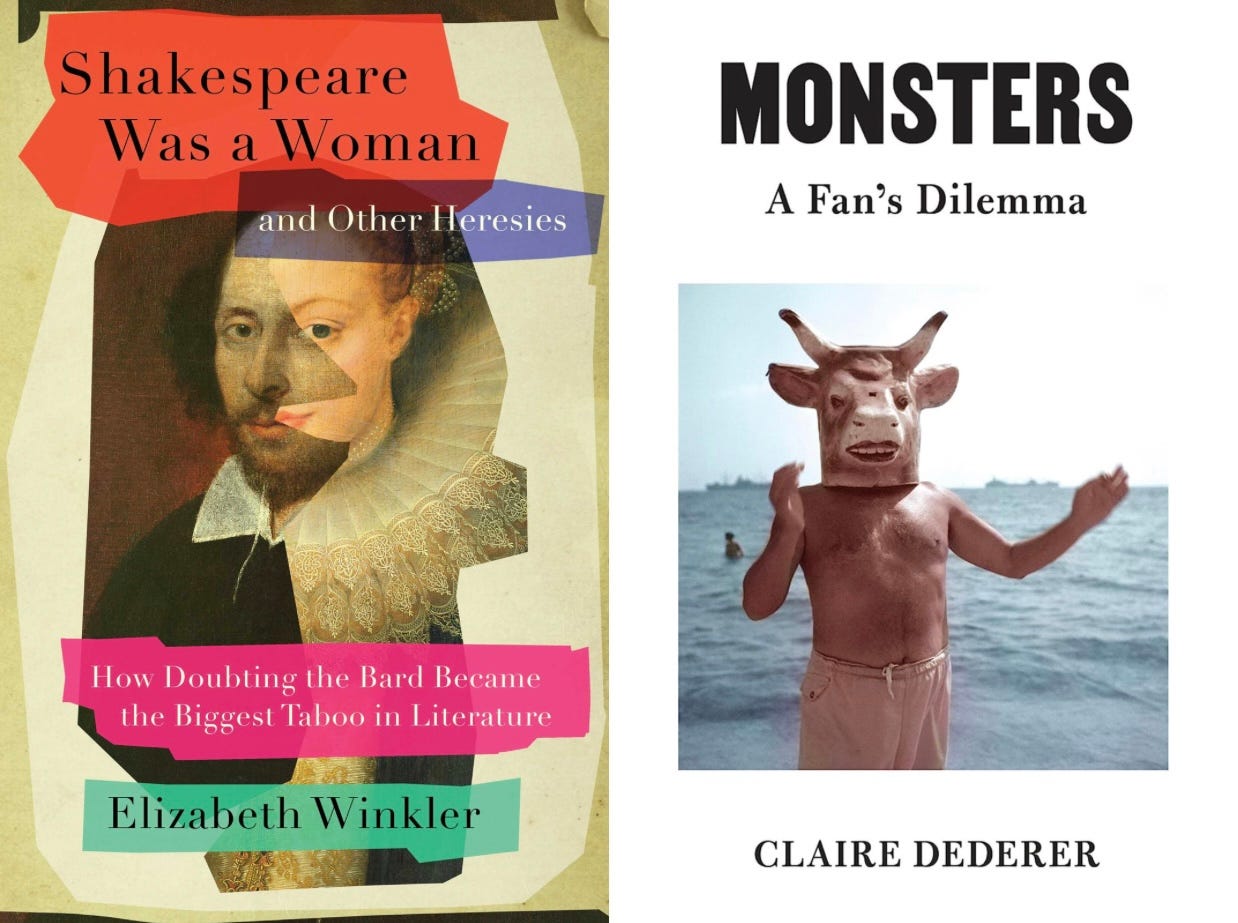

You see more of the same, if to a lesser extent, in nonfiction, too. Take a look at the covers of Shakespeare Was a Woman and Other Heresies and Monsters, two of the books I wrote about in “Fame’s Inflection Point”:

I loved both of these, but which of them would you guess was more scholarly? It’s Winkler’s, which is gorgeously written and could have easily been published by an academic press. Personally, I would have preferred a title for it like: Shakespeare and the Psychology of Belief or something, and a cover more akin to American Prometheus, which I think its erudition deserves:

The great irony of all of this is how well Big-Bomb art by women often performs when it is branded appropriately. Look back up at Monsters—it’s a great cover. Tonally appropriate for the book. Brightly menacing; sophisticated. (I’m sort of dying over its visual similarities to my paperback mockup from a year earlier.) And Monsters has been immensely successful! Reviewed in the New Yorker, the New York Times—I’ve seen it everywhere this summer.

Then I think of Kathryn Bigelow and The Hurt Locker; of, above all, Joan Didion. Don’t get me wrong, Didion was a great writer, but her branding was even better. And her chief success on this score was that her work was treated with a sort of emphatic gender-neutrality, ideally positioned at the 2x2’s origin with her name in a giant font in a way that is frankly still too often reserved for men.

There’s a direct relation between all of this and the fact I’m now working on a novel about math and basketball. If I’m so fortunate as to publish again, I’ll have a little request for the commercial departments:

Brand it as if I was a man.

Kenough said,

ANJ

Would invest in a “Brand it as if I was a man” t-shirt campaign.

If, as you say, Barbieland narratives are really about "setting up the right readers—the novel’s target audience—for an enjoyable experience in line with their narrative expectations," I would argue that you could put most horror movies in the lower right quadrant of your 2x2. The plots rarely revolve around "big and weighty" themes (although it is funny reading the critics as they squirm around trying to extract a big takeaway from some of them); they are usually highly contrived situations designed to appeal to the fans' tastes.