Ciao amici,

I’ve mentioned

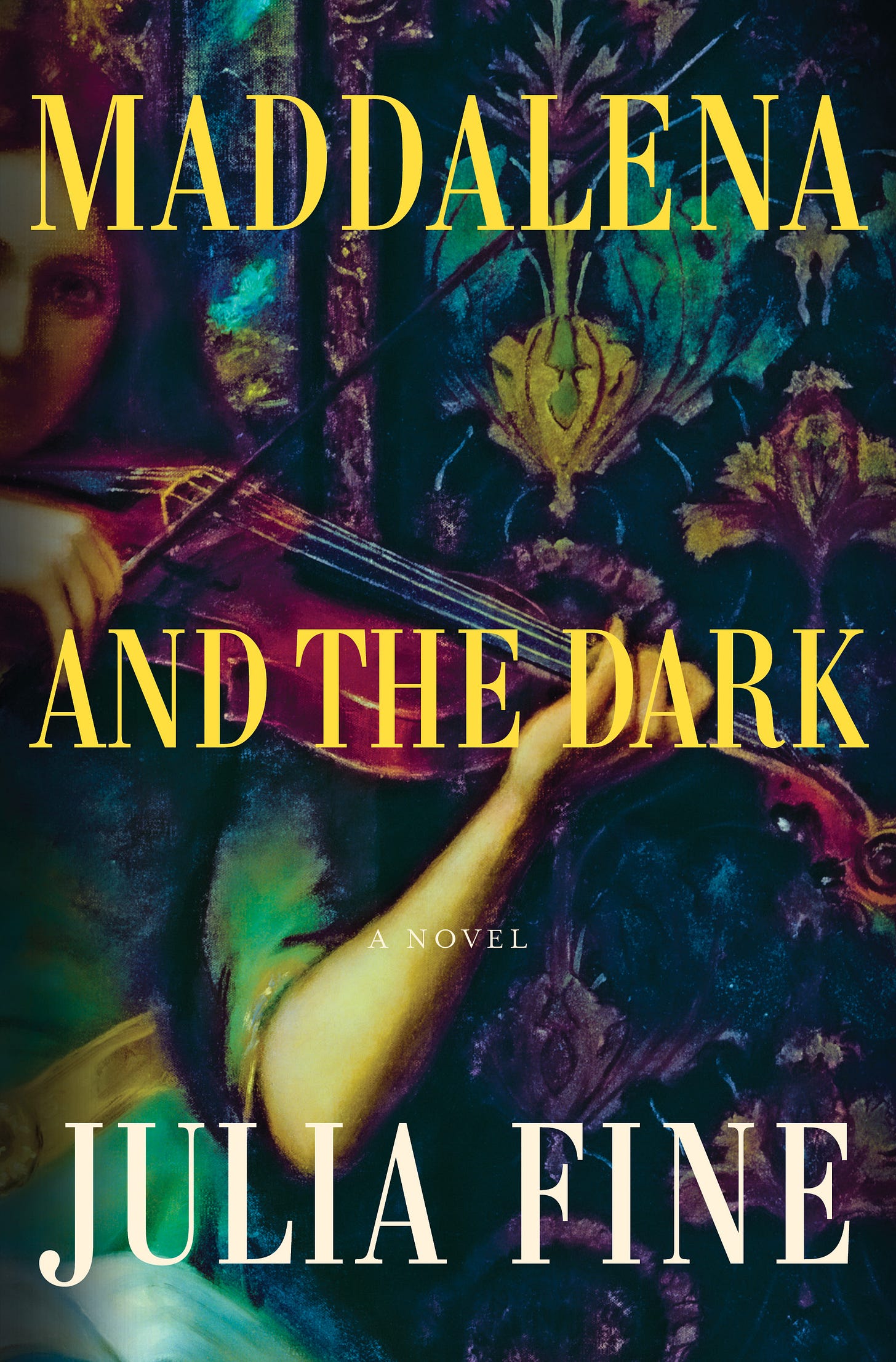

’s latest book, Maddalena and the Dark, a couple of times now—it’s one of the best things I read last year, and a choice-plot novel if there ever was one. And today, in honor of its publication, I have the great pleasure of sharing an excerpt from it with you.This early chapter epitomizes so much of what I love about the novel—its music, its material splendor, its concupiscence. As a child-violinist who travelled to Venice to play Vivaldi in middle school, I wasn’t exaggerating when I said it felt like Maddalena was written specifically for me. On the sheer basis you subscribe to this newsletter, I suspect it will also be for you—and your friends, so please do send it round.

I’ll be speaking to Julia on the Washington, DC stop of her book tour this coming Saturday, June 17, at 3pm at Politics & Prose (Connecticut Ave). We’d love to see you there! And if you have suggestions for questions I should ask her, please tell me in the comments below.

Luisa

The game has begun: who might look without herself being seen, who might catch the other out. The more exaggerated Maddalena’s indifference, the more desperate Luisa becomes to hold her notice. With Maddalena nearby, Luisa trips over her shoes as she leaves the dinner table, tangles herself in the lace bobbin while at work. And Maddalena is always nearby, on the lips of every girl—the way she styles her hair, her husky solfeggio, her brothers, who come to see her when they can, despite the Pietà’s rules and the Priora’s disapproval.

“The youngest is handsome,” says Chiara as they wait for the maestra during group music lessons, her chair dragged into the geometric swaths of sun that slant through the high windows. “But the oldest is clever.”

“And the middle?” Adriana leans forward.

“The middle is a rogue.”

Luisa pretends to busy herself with her bow, searching out dirty hairs.

“Tell more!” says Adriana, invigorated.

“Well—” Their two dark heads are bowed together, giggling, when Maestra Simona comes in. Luisa thinks she’ll reprimand them, but even the maestre, even the Coro, have succumbed. Instead of arpeggios, they all spend the next fifteen minutes discussing the cut of Andrea Grimani’s cloak. Luisa comes away from the group lesson with little new knowledge of either the maestro dei concerti’s newest sonatas, or of Maddalena herself, who sweeps in half an hour late, smelling of brine and snuffed candle.

Where were you? No one asks, but as they put away the instruments Luisa lingers, trying to glean answers from the dirt at Maddalena’s hemline, the one escaping curl of hair at the nape of her neck. When Chiara grabs her hand to leave, Maddalena shakes her head.

“My—” She makes a half-hearted gesture toward her sheet music. Chiara’s nostrils flare a moment before her face resumes a studied placidity. It’s been a week since Maddalena’s arrival, and though a tentative hierarchy has been established, lines are not yet fully drawn. Right now, Maddalena’s good graces mean immediate social capital, make Chiara remarkable—what every foundling girl at heart most hopes to be. To walk with Maddalena means the other girls will look at her the way they once looked only at soloists—a mix of reverence and jealousy that earns the final roll at dinner, an extra blanket when the dormitory window creaks. But Chiara is pragmatic. Who is to say what next week will bring, or the week after? She frowns and leaves the room, and here are only Maddalena and Luisa. Neither girl speaking, neither girl looking away.

Maddalena’s eyes are dark, a black that in a certain light shines indigo. She looks at Luisa and raises her fist to rest against her mouth. Luisa feels anointed. She thinks she should do something momentous; something grand must be expected. Still grasping her violin, she feels each muscle in her hands and the back of her neck.

Luisa lightly twists the peg of her A string, a small movement at first, barely enough to change the sound. But Maddalena is watching, is curious, and so Luisa turns the peg again, feels the string tighten, feels the pressure of the string against the bridge. It is frayed; it could snap. Another turn, and Luisa’s like a tightrope walker actively choosing not to look down while creeping out above a city square. Luisa’s eyes on Maddalena’s eyes, Luisa’s eyes stinging. And then Maddalena shakes her head slightly, and lowers her fist from her chin. She almost laughs, a sound like a swallowed belch. It’s too late for either girl to speak—they’ve passed the point at which conversation would be comfortable. Maddalena smiles like a spy encountering one of her own in the field. She opens her mouth, grins again, then shuts it.

When Maddalena leaves the room, Luisa collapses. Maddalena has taken all the air.

Luisa’s mind often drifts during chapel. Weekdays, she thinks of the mistakes she has made at rehearsal, of that night’s supper, of Don Antonio Vivaldi, who has recently been promoted to maestro dei concerti and might—these are her own private fantasies, so anything is possible—find her practicing and make her his muse, guaranteeing her a future with the Coro. The Ospedale della Pietà houses hundreds of girls and women, but only sixty are figlie di coro, daughters of the choir. While these elite few play solos written to their strengths, sleep in private rooms, and venture out to dine on softshell crab in the finest Venetian homes, the rest, the figlie di comun, who have not married and chose not to take vows, remain in the compound and make lace or embroidery, sweep the kitchens, wash the linens. Luisa doesn’t yet know to which caste she’ll belong.

On Saturdays and Sundays the Coro performs for Venice, and rows of rich-robed men and women can be observed from Luisa’s place in the back loft with the rest of the uninitiated foundlings. The morning after their encounter in the music room, instead of studying the foreign dignitaries in the front pews, it’s Maddalena that Luisa dissects. The new girl sits with Chiara, shifting her jaw, not bothering to hide her boredom. There’s a tear at the hem of her skirt. A birthmark just below her left ear. She tilts her head to whisper something to Chiara, whose mouth tightens in a stifled smirk, though she continues to look down through the grate at the altar. Luisa tries to think of what Maddalena might have told her—a little joke about the way the priest’s voice cracks as he intones, something outrageous about one of the noble families seated in the nave. She doesn’t usually care about the other girls’ closeness. She doesn’t even believe that what’s between Chiara and Maddalena is closeness, just proximity. Luisa has not seen Maddalena look at Chiara—has not seen her look at anyone—the way she looks at Luisa, really the way she pretends not to look at Luisa, miming indifference once Luisa meets her gaze, but certainly looking, every day since that first day.

Maddalena’s head turns quickly now, her eyes finding Luisa’s. Luisa’s cheeks redden, Maddalena thumbs the hem of her sleeve. They’re saved by the Coro, entering the large balcony near the chancel from a back staircase that connects the Ospedale to the church. The women fill the lengthy choir loft, a stream of bodies in white dresses with shadowy instruments, impossible to see clearly behind the ornate wooden grate that runs its full perimeter. If girls must play music, the church has decided they’ll do so invisibly, though the sharp-eyed can still peer through the patterned wood to catch an elbow, the line of a cheekbone, the glow of a candle against the hollow of a throat.

Today Anna Maria, the Coro’s darling, has the solo, which has been written specifically for her by Maestro Vivaldi. She stands near the front of the grate, her violin the bubbles in a glass of prosecco. Her violin the fireworks out over the lagoon. Her violin perfection.

Listening to Anna Maria makes obvious Luisa’s lack. It doesn’t matter how much Luisa wants the Coro, how much she cares. A love for an instrument, even a predisposition, means nothing at the Pietà, where not all girls are Anna Maria but many come close. Even the littlest girls in the novices’ choir are as skilled as most professional Venetian musicians. It’s not desire but talent and hard work that makes them elite, plus the death or the retirement of one of the older girls—now women, but Pietà girls forever, Pietà girls from the day they were left at the window in their Moses baskets, the day their parents peeled sticky fingers off threadbare skirts. They were marked at the heel when they arrived as infants, so that they would always be Pietà girls: the iron hissing, the wound blistering, slow to darken.

Luisa views that branding as a baptism. One morning the figlie found a baby where there had not been a baby before—Luisa might be the illegitimate daughter of a wealthy man’s mistress, she might be a changeling, she might have been found wailing in a cradle next to a mother dead of fever, or she might have been a tenth and impossible mouth to feed. She cannot know. But she belongs now to the Pietà—no matter which tier she ends up in—and she belongs so transparently that no one can deny her.

They have a good life here, if cloistered. The Pietà girls are allowed to leave the compound only to be treated for sickness or, if they are lucky, to perform. In these rules the Pietà is no different than the nunneries speckling the city. Luisa thinks that hers is not so very different from the lives of other girls. It might even be better. After all, she has a home. She has been claimed, her scar a sign that she’s wanted. Maddalena, of course, has no brand. Maddalena has a surname. She has brothers who visit on Sundays. She has a family palazzo on the Grand Canal and a countryside villa in the Veneto. If Maddalena wants to whisper through Vespers or remark upon the smallpox scars that crater Betta dal Clarineto’s cheeks or mimic Maestra Vittoria’s slow mathematical recitations, she can and will do. For now, while her father lives and prospers and her brothers still dote, Maddalena can behave as she pleases. Luisa tries to convince herself that Maddalena’s is not a better life, just different.

Luisa feels Maddalena’s gaze, though she will not tear her own eyes from Anna Maria, the patterned grate in front of her, the orchestra behind. Whispered air at the back of Luisa’s neck, although no one is whispering. The little hairs at her nape stand on end. Why, she wonders suddenly, should Maddalena have a rip in her skirt? They’re all expected to be well turned out, especially at Mass, especially Maddalena, who they’ve been assured will be treated no differently despite her unusual status, although, of course, this has not proven true. If Luisa were to come to Mass with shredded skirts, she’d be sent to consider her sins in solitary confinement, or the figlie might make her skip a meal. Yet here is Maddalena, bold in her dishevelment, unpunished and unafraid.

The music ends in a virtuosic cadenza, and the congregants let out an appreciative exhale. The priest resumes, the incense thickens the aisles.

EXCERPTED FROM MADDALENA AND THE DARK. COPYRIGHT © 2023 BY JULIA FINE. EXCERPTED BY PERMISSION OF FLATIRON BOOKS, A DIVISION OF MACMILLAN PUBLISHERS.

SENSATIONAL !

Ceciia Bartoli (mezzo soprano ) performing some of the repertoire of farinelli

https://youtu.be/zvF_hjQwujg

I will have to read the book, thanks. foe the excerpt.

Check this out ! outstanding :

https://youtu.be/y3fzhMnGs5E