Bards & heretics

an excerpt from Elizabeth Winkler’s Shakespeare Was a Woman and Other Heresies (plus a salon!)

Dear lovers of truth and uselessness,

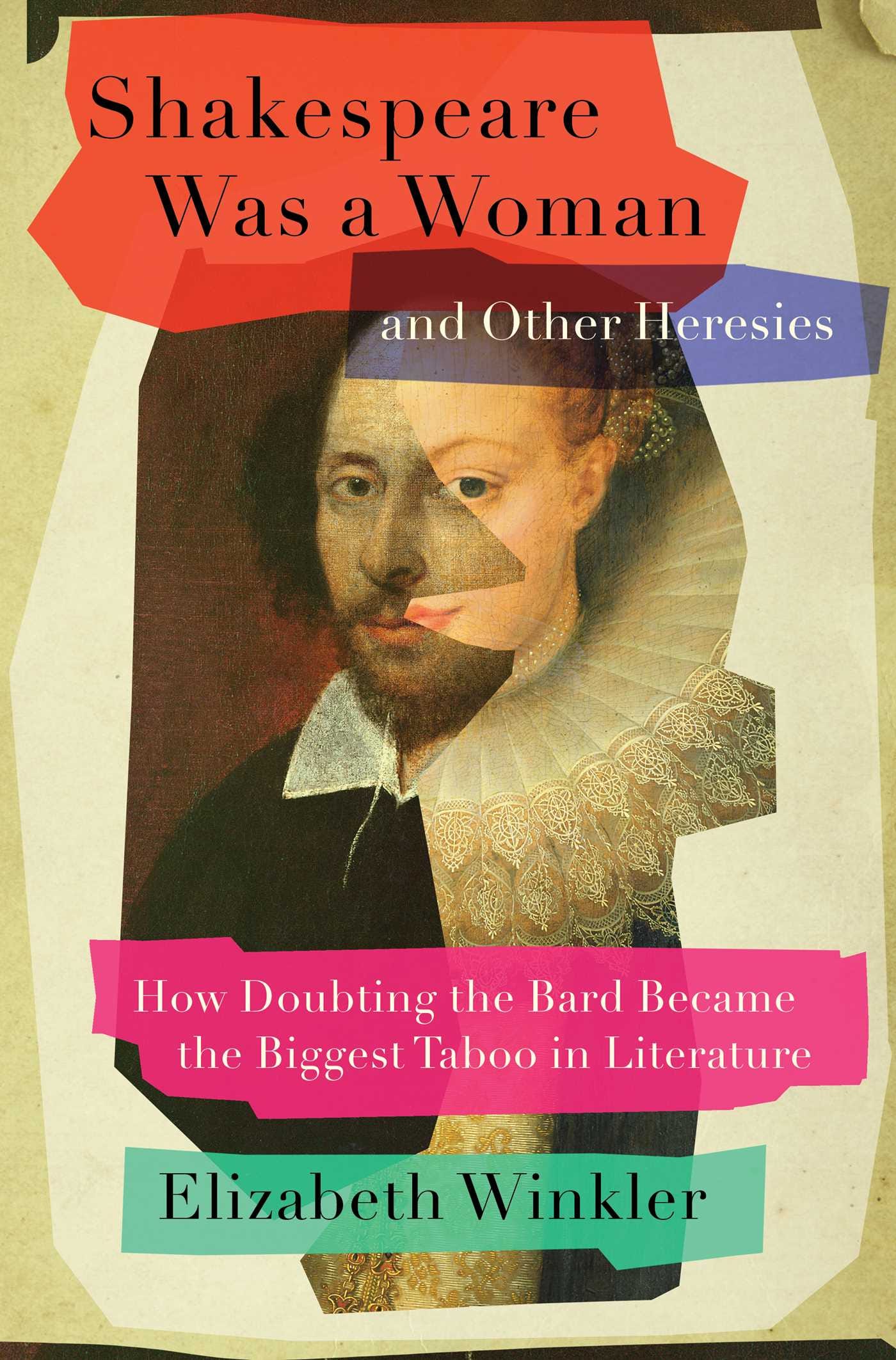

It’s no secret I’m besotted with Elizabeth Winkler’s book Shakespeare Was a Woman and Other Heresies: How Doubting the Bard Became the Biggest Taboo in Literature. Rare is the work of such uncompromisingly rigorous scholarship that is also so deliciously fun. I’ve written about it previously here & here & here; bought it in every format; sent a copy to my parents. I recommend it every chance I get—and today I have a plum one, because in honor of its upcoming paperback publication on April 23 (auspicious!) and our

salon the next day, I’m thrilled to share an excerpt, courtesy of Simon & Schuster.The passage below is from the second chapter, in which Elizabeth weaves a veritable intellectual smackdown of super-scholar Stephen Greenblatt’s Shakespeare “biography,” Will in the World, into the dispassionate presentation of facts supported by the historical record. In it we can already see some of the book’s most fascinating questions taking shape—of special interest to yours truly: why do Shakespeare scholars—a group of highly intelligent, supremely well-educated, sophisticated, and otherwise reasonable people—all but monolithically become Stratfordian zealots amid such scant and dubious evidence?

In other words, how did did Shakespeare scholars develop a blind spot in the center of the mirror?

Elizabeth and I will discuss precisely this April 24 at 8pm EST. (Novelists conversely boast a long and illustrious history of heretical doubt—see Nabokov; James.)

I hope some of you will join us on Zoom. Will be highly interactive! You can find all the details and sign up on Interintellect’s site here.

In the early years of the reign of Queen Elizabeth I, a child was born in the market town of Stratford-upon-Avon (population: approximately 1,500) to John, a glove maker, and his wife, Mary. The exact date of his birth is unknown, but a baptismal record for April 26, 1564, reads, “Gulielmus filius Johannes Shakspere” (“William son of John Shakspere”). Subtracting a few days, biographers locate his birth on April 23, the feast of Saint George, patron saint of England.

How did the boy from Stratford become the world’s greatest playwright? Though scholars claim not to participate in the authorship debate—not to recognize it—Shakespeare biographies are entirely about the authorship question. They try to make the case for Shakespeare, to explain how he did it. They begin like a folktale or the legend of a saint, deep in the heart of England, wrapped in wildflowers and rolling green hills. See, for instance Will in the World: How Shakespeare Became Shakespeare, the 2004 New York Times best seller by the Harvard scholar Stephen Greenblatt. “Let us imagine that Shakespeare found himself from boyhood fascinated by language, obsessed with the magic of words,” Greenblatt begins.

Let us imagine.

It is alluring, inviting, and entirely make-believe. Whether William of Stratford was obsessed with words is unknown—but if you assumed he wrote the works, then he must have been. “There is overwhelming evidence for this obsession from his earliest writings, so it is a very safe assumption that it began early,” Greenblatt defends his assumption, “perhaps from the first moment his mother whispered a nursery rhyme in his ear: Pillycock, pillycock, sate on a hill / If he’s not gone—he sits there still.” On the very first page of his biography, Greenblatt conjures a scene—Shakespeare’s mother singing to him—for which no evidence exists.

A few facts are known of the family. His father, John, who came from the nearby village of Snitterfield, was fined for keeping a dung heap outside his house. Across different tellings of the tale, the dung heap takes on a kind of symbolic quality. Anti-Stratfordians recount the detail gleefully—as though to say, this story stinks of shit. Stratfordians, in hagiographic fashion, tend to airbrush out the dung heap. John engaged in various trades around town: in addition to glove maker, he was also a “brogger” (an unlicensed wool dealer), a dealer in timber and barley, a landlord, and a local official, rising from ale taster (responsible for ensuring the quality of bread, ale, and beer) to bailiff (chief magistrate of the town council). He signed documents only with a mark, suggesting that he could not write his name. “Most plain-dealing men in early modern England used marks because the majority of the population was illiterate,” explains the historian David Cressy. “More than two-thirds of men and four-fifths of women in the seventeenth century could not write their names.” Numeracy, not literacy, was needed to conduct business in Elizabethan England, and reading and counting were taught before writing, so some could read but not write. Of the nineteen elected officials in Stratford while John Shakespeare held office, only seven could sign their names. His wife could not write her name, either.

Next, the biographies usually tell us about the genius’s school days. The slight awkwardness is that we don’t know if he ever went to school. He may have attended the local grammar school—his father’s position on the town council would have allowed him to attend for free—but the school’s records have disappeared. In order to write the plays, however, he must have received an education, so scholars assume he attended. They have tried to squeeze the most out of the grammar school, imagining it as the site of a rigorous classical education, but Renaissance writers deplored the quality of the provincial grammar schools—generally one-room schoolhouses in which all levels were taught by a single schoolmaster, and writing materials were so “scarce and expensive” that Latin grammar was instilled by recitation and the rod. If he did attend, it probably wasn’t for long. In the 1570s, his father was prosecuted for usury and illegal dealing in wool. By 1576, when William was thirteen, John Shakespeare withdrew from public life. It is suspected that he either fell into debt or lowered his profile to continue pursuing his illegal wool-dealing. Scholars believe William likely left school to help support the family. He had five younger siblings.

At eighteen, he married. Friends of the bride’s family signed a financial guarantee for the wedding of “William Shagspere and Anne Hathwey,” who was three months pregnant. The surname appears in various forms: Shakspere, Shagspere, Shaxpere. Elizabethan spelling was not standardized. In the Stratford records it appears most often as “Shakspere,” with a short “a,” though on the title pages of the plays and poems it would generally appear as “Shakespeare” or “Shake-speare.”

The couple had a daughter, Susanna, and three years later twins Hamnet and Judith—apparently named after their Stratford neighbors Hamnet Sadler, a baker, and his wife, Judith. Another gap stretches from 1585 to 1592. Scholars refer to these as the “lost years,” like the lost years of Jesus from his childhood to the beginning of his ministry. Greenblatt imagines that he spent them as a tutor to a Catholic family in the north of England, where he met a Jesuit priest named Edmund Campion. (“Let us imagine the two of them sitting together . . . Shakespeare would have found Campion fascinating.”) But there is no evidence that Shakespeare was a tutor or that this thrilling meeting of minds ever took place.

The biographies are riddled with speculation: Shakespeare “could have,” “might have,” “must have,” “probably,” “surely,” “undoubtedly,” they muse, conjuring baseless scenes and elaborating tenuous theories in an attempt to connect the man to the works. They are the very worst kinds of biography: fiction masquerading as history. Scholars are not unaware of the problem. Will in the World, Greenblatt’s best seller, was censured by a colleague in the London Review of Books as “biographical fiction.” But it was beautifully written and vividly imagined, and so, in spite of its liberties, it became a finalist for the National Book Award and the Pulitzer Prize.

Other scholars, encouraged by Greenblatt’s success, pumped out more biographies. Despite, or perhaps because of, their fictional qualities, Shakespeare biographies have been popular with readers since the Victorian age, telling a rags-to-riches story of a hero whose early hardships elicit sympathy and whose rise to fame and wealth offers the satisfaction of virtue justly rewarded. The cognitive scientist George Lakoff calls the rags-to-riches structure one of our “deep narratives,” recurring again and again in our cultural and political life—in religious stories, fairy tales, and the campaigns of charismatic politicians. Our attachment to it is difficult to shake. The story of Shakespeare’s rise from humble origins, from an apparently illiterate family in a provincial town, to literary immortality is cozy, comforting, compelling, a tale with all the warmth, cheer, and assurance of English firesides. But it is an imaginative construction. (“What matters is not the true story, but a good story,” wrote the scholar Gary Taylor, reviewing Greenblatt’s book.) Over the years, scholars have imagined a Protestant Shakespeare, a secret Catholic Shakespeare, a republican Shakespeare, a monarchist Shakespeare, a heterosexual Shakespeare, a bisexual Shakespeare, a Shakespeare who hated his wife (and thus left her the second-best bed), a Shakespeare who loved his wife (and thus left her the second-best bed), a Shakespeare who, before taking up the pen, must have been a roving actor or a schoolmaster or a lawyer or a soldier or a sailor. Being nothing, Shakespeare can be anything—anything his biographers desire.

In 2016 scholars convened a conference called Shakespeare and the Problem of Biography. “Shakespeare’s life exists as a kind of black hole of antimatter in relation to the vast nebula of his fame,” Professor Brian Cummings of the University of York observed in his opening remarks. “Could it be that his fame has grown through this very lack of identity to pin a more ordinary life to, so that he is the perfect container for our desire and creative empathy?” Cummings lamented the difficulty of reconstructing Shakespeare’s life, admitting that “the largest lacuna of all is the mystery of how Shakespeare ever got to be a writer in the first place.”

EXCERPTED FROM SHAKESPEARE WAS A WOMAN AND OTHER HERESIES: HOW DOUBTING THE BARD BECAME THE BIGGEST TABOO IN LITERATURE. COPYRIGHT © 2023 BY ELIZABETH WINKLER. EXCERPTED BY PERMISSION OF SIMON & SCHUSTER.

We can't wait!! <3

This is so good, and has me thinking about fictionalizations of Shakespeare, like Hamnet and Shakespeare in Love, which are so fun bc they interact with the legend created by the problematic biography.